1.Monolix Documentation

Version 2024

This documentation is for Monolix starting from 2018 version.

©Lixoft

Monolix

Monolix (Non-linear mixed-effects models or “MOdèles NOn LInéaires à effets miXtes” in French) is a platform of reference for model based drug development. It combines the most advanced algorithms with unique ease of use. Pharmacometricians of preclinical and clinical groups can rely on Monolix for population analysis and to model PK/PD and other complex biochemical and physiological processes. Monolix is an easy, fast and powerful tool for parameter estimation in non-linear mixed effect models, model diagnosis and assessment, and advanced graphical representation. Monolix is the result of a ten years research program in statistics and modeling, led by Inria (Institut National de la Recherche en Informatique et Automatique) on non-linear mixed effect models for advanced population analysis, PK/PD, pre-clinical and clinical trial modeling & simulation.

Objectives

The objectives of Monolix are to perform:

- Parameter estimation for nonlinear mixed effects models

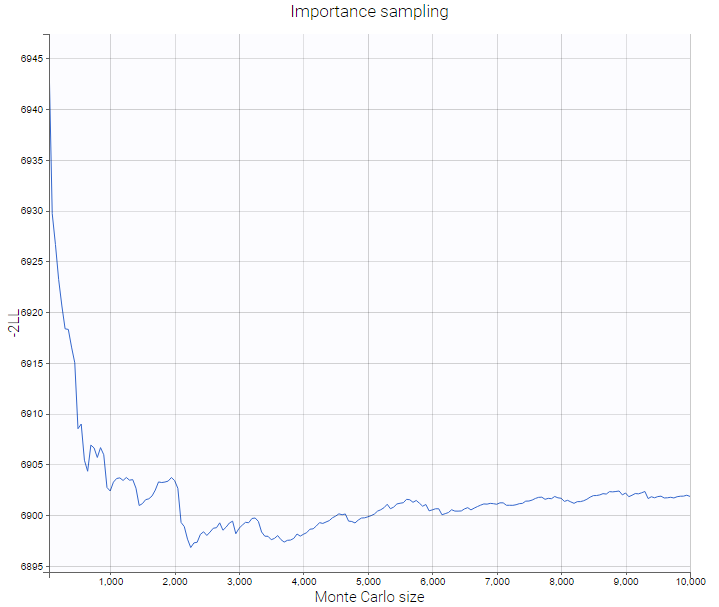

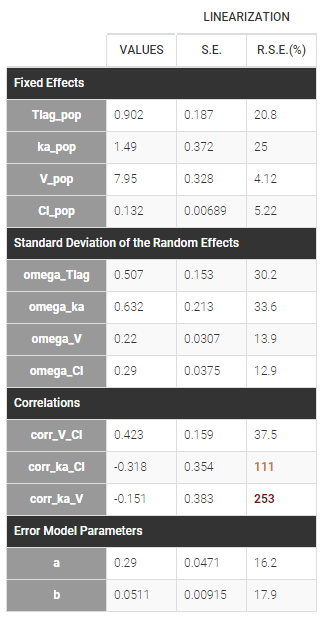

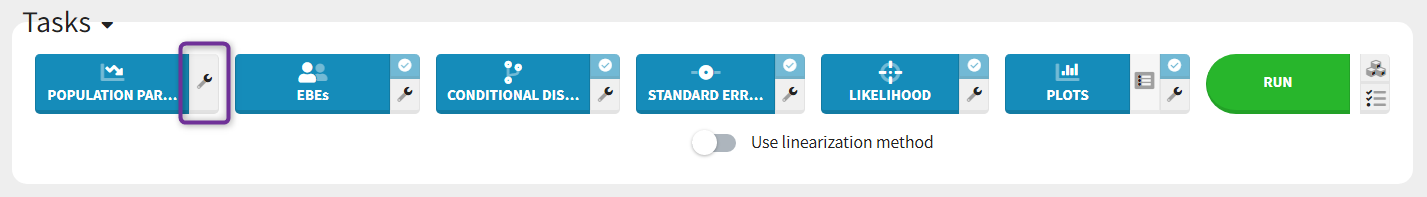

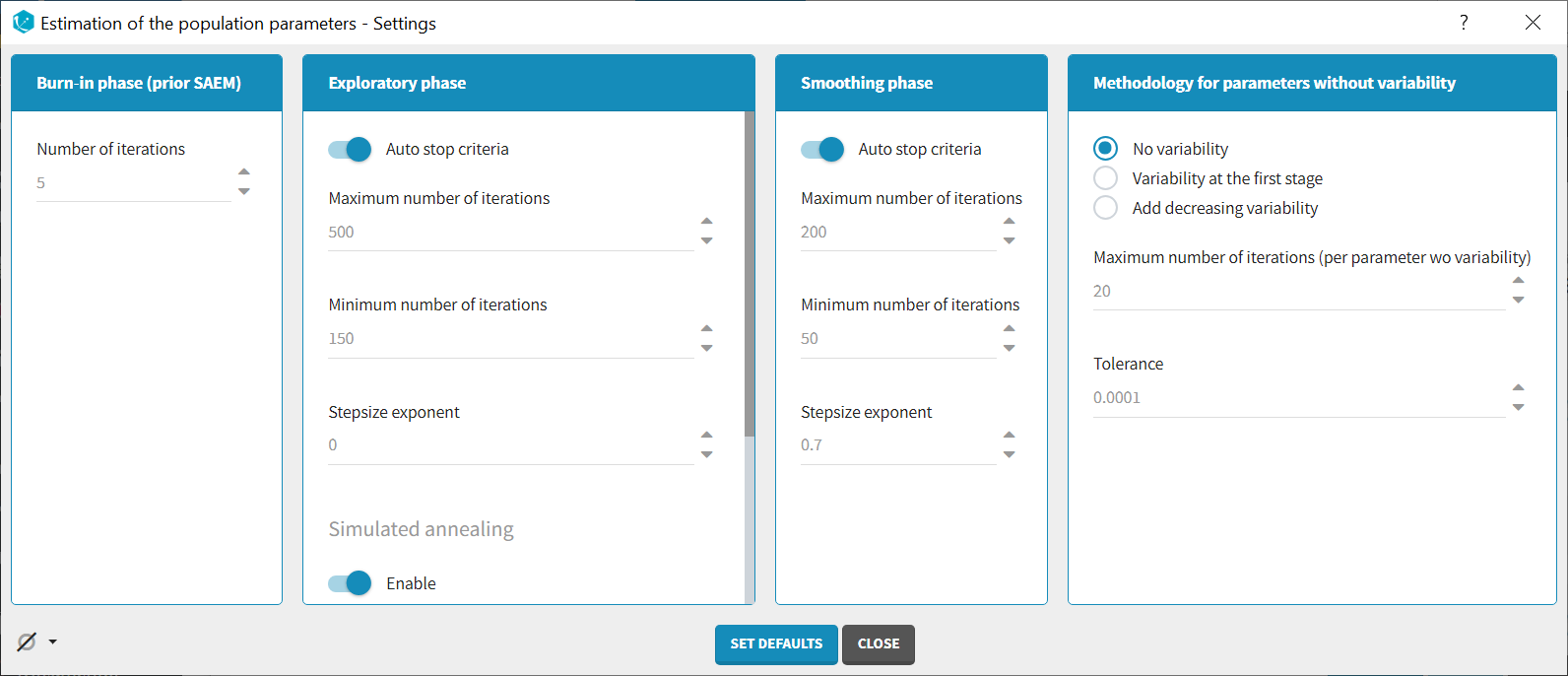

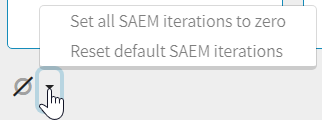

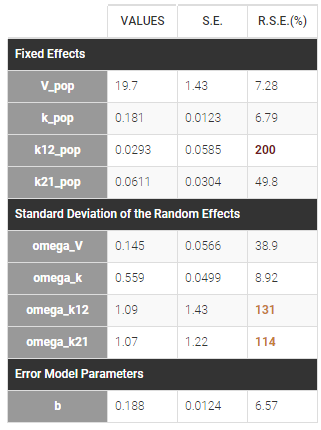

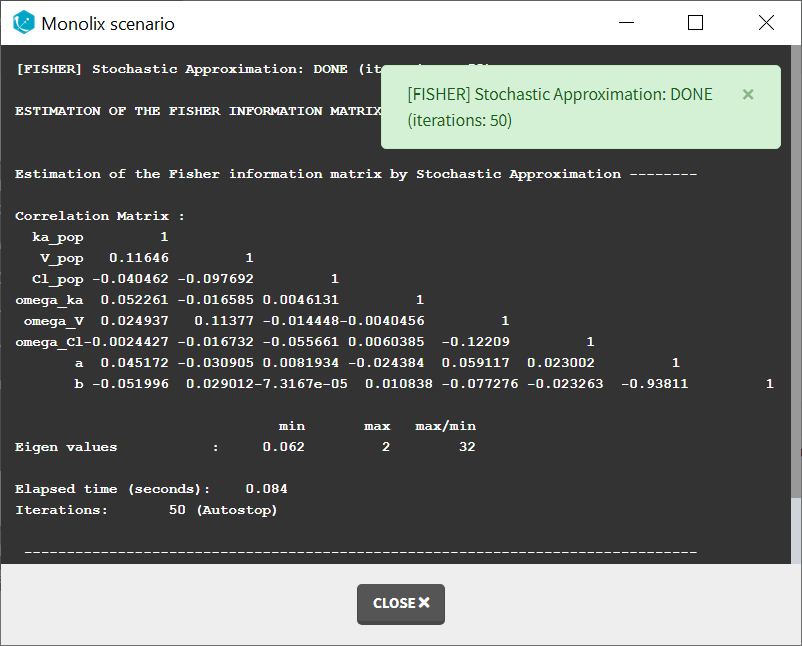

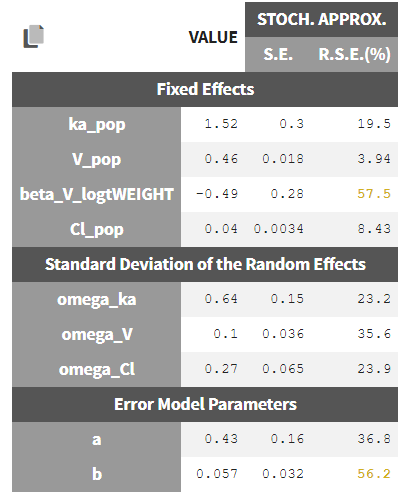

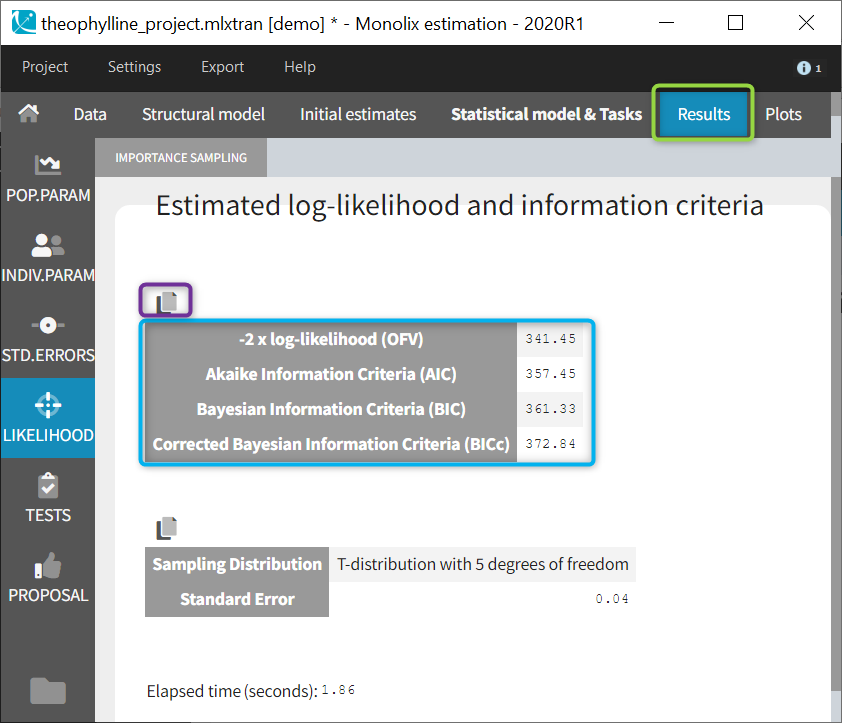

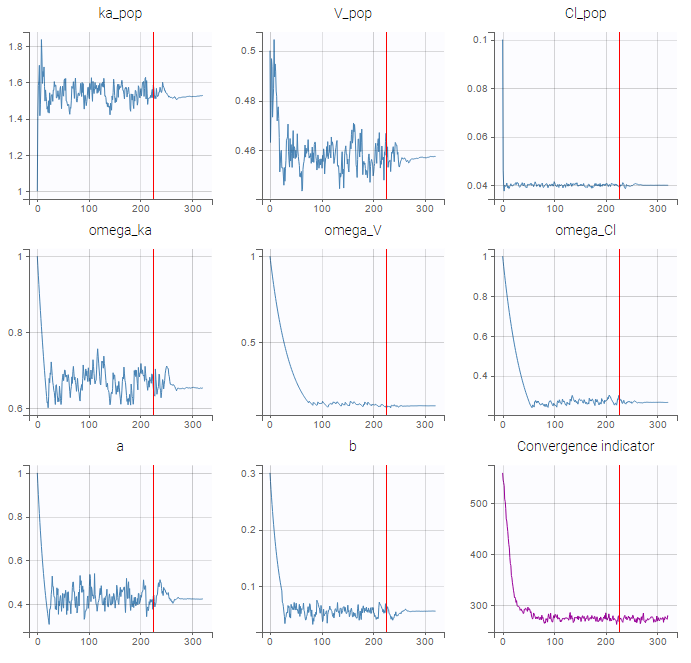

- estimating the maximum likelihood estimator of the population parameters, without any approximation of the model (linearization, quadrature approximation, …), using the Stochastic Approximation Expectation Maximization (SAEM) algorithm,

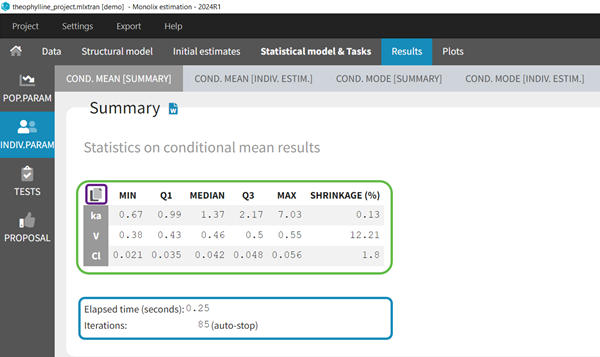

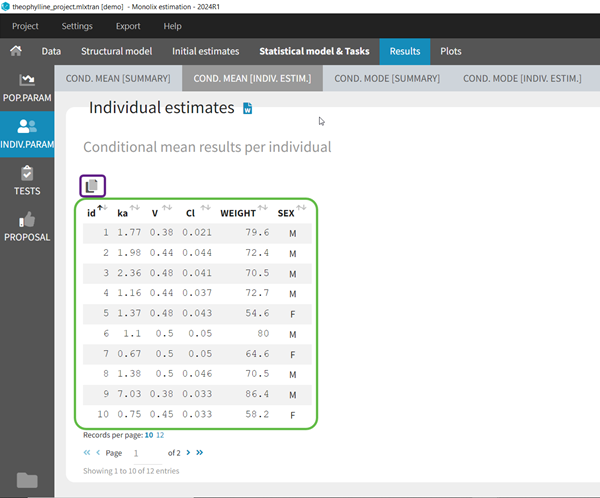

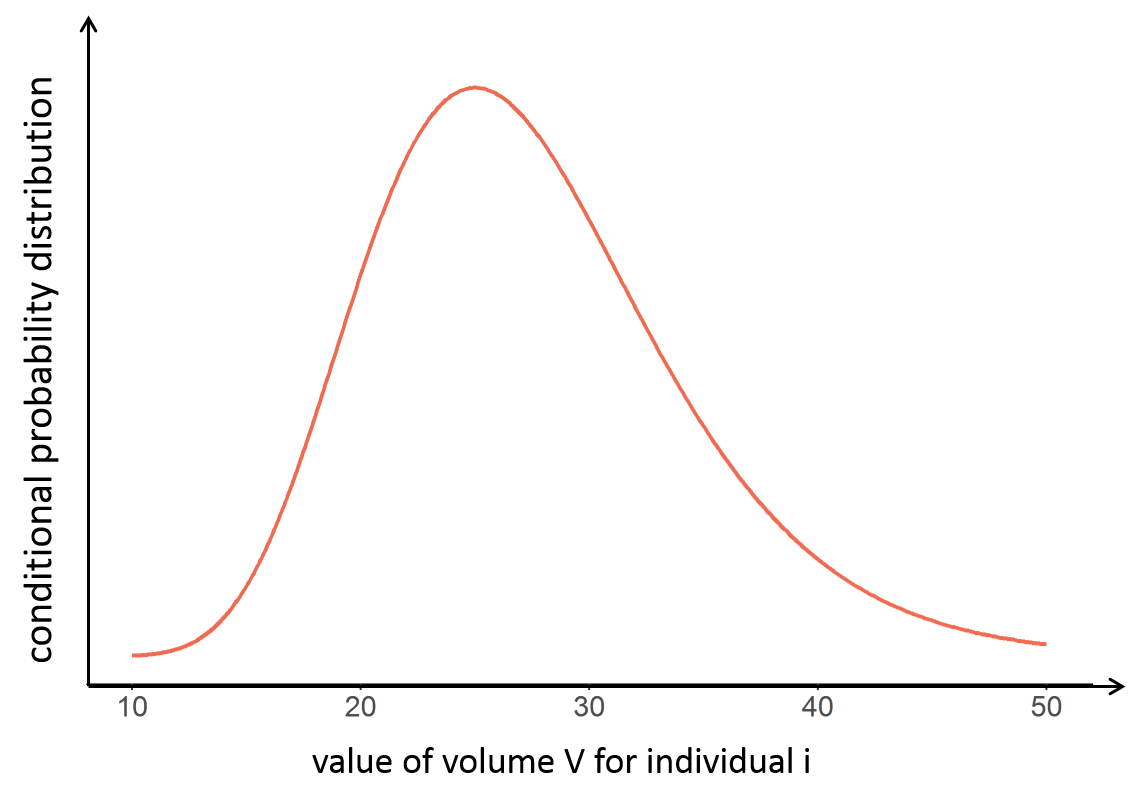

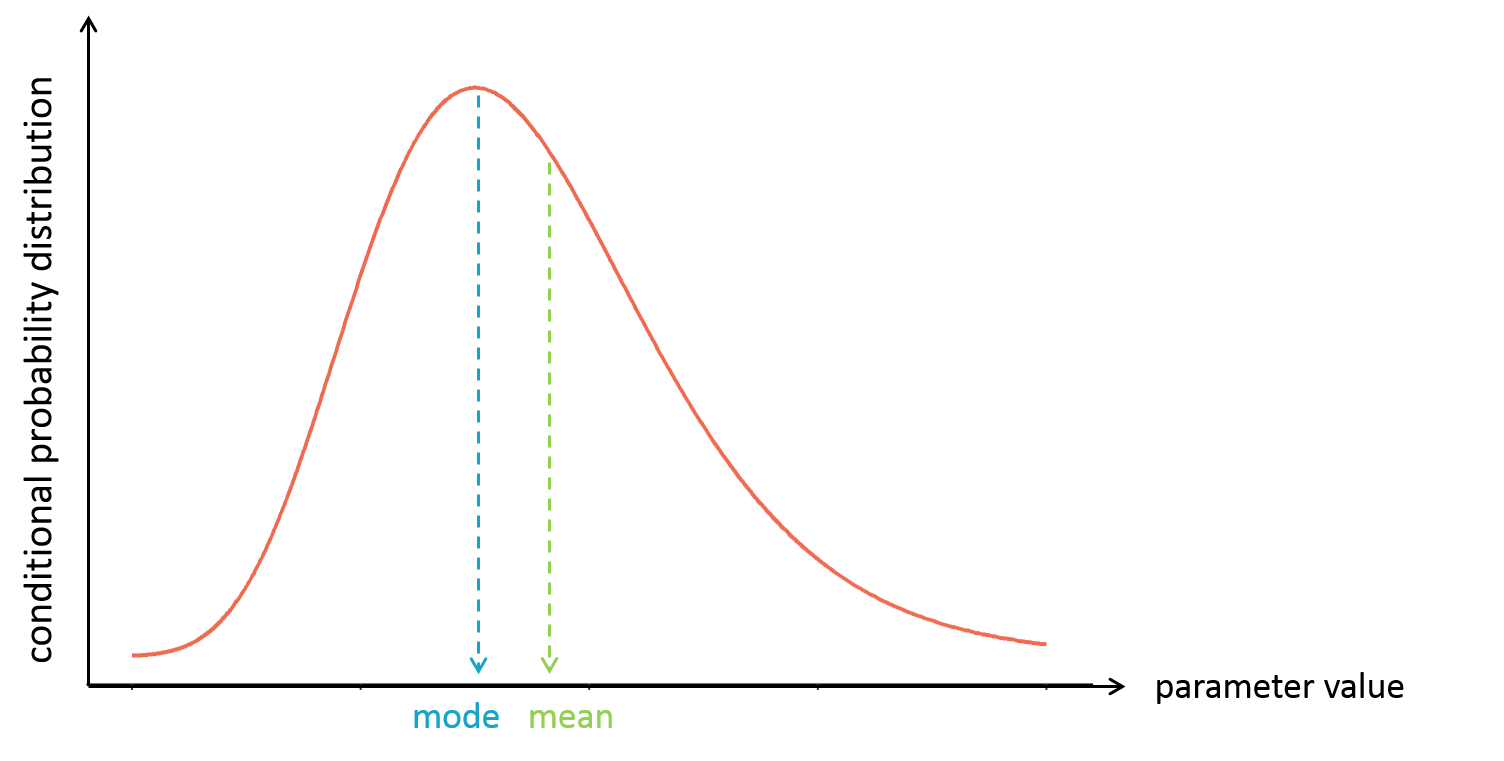

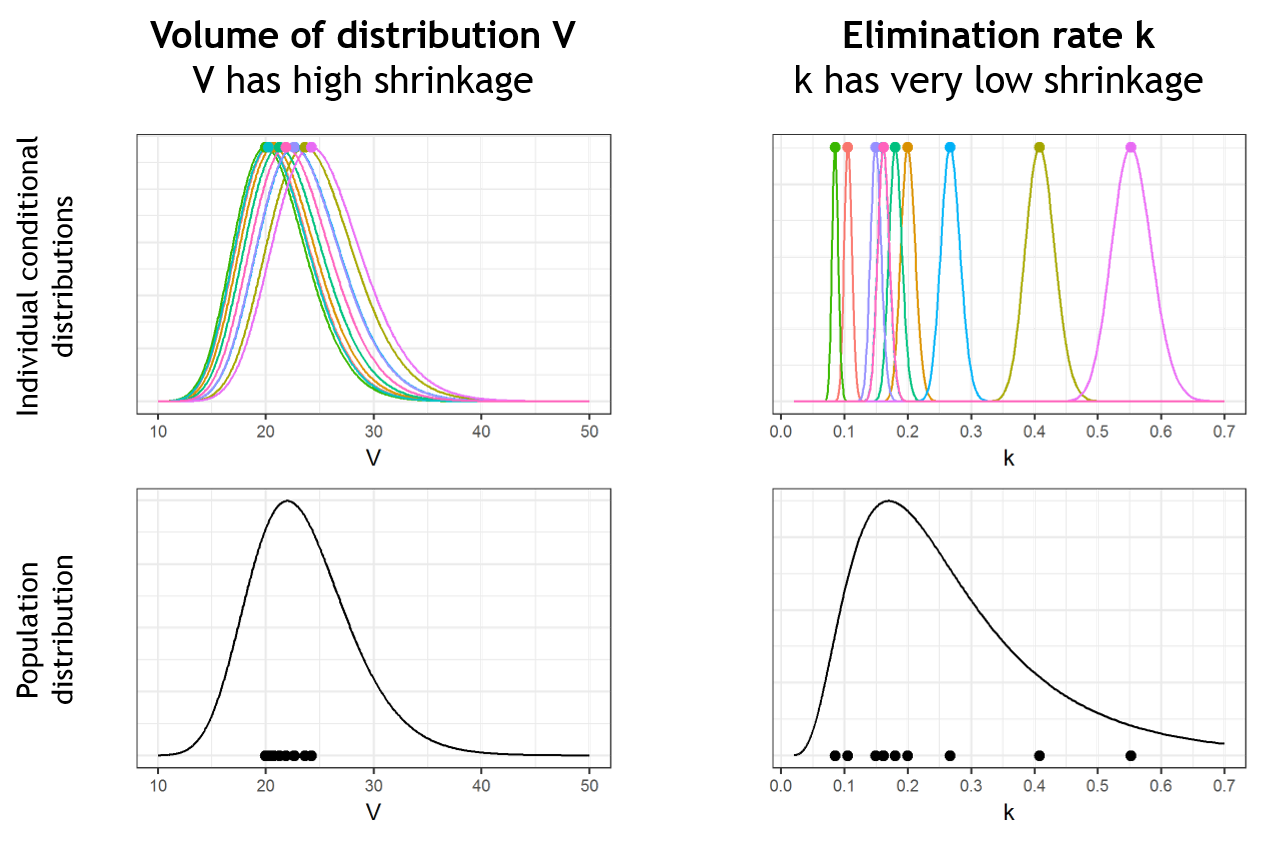

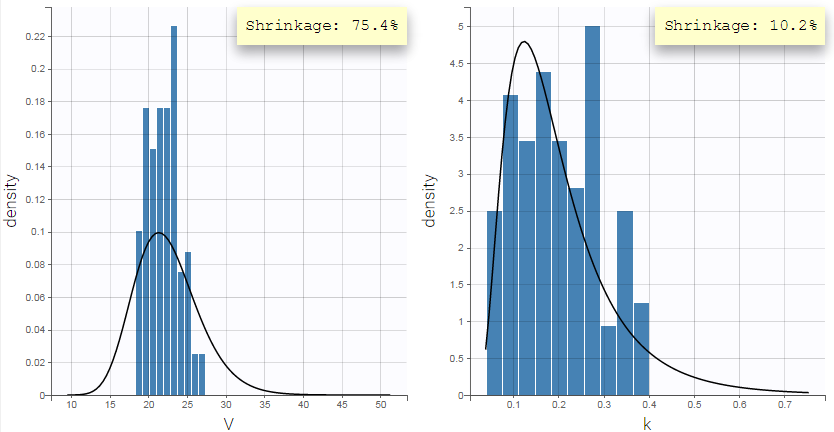

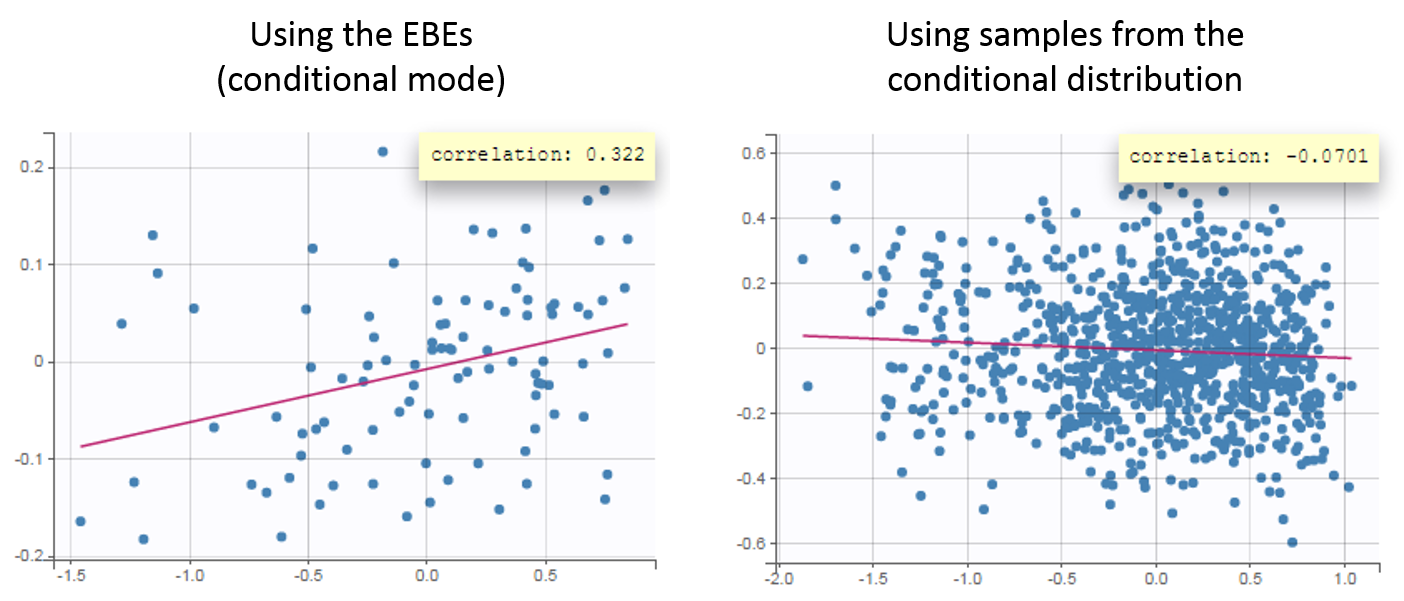

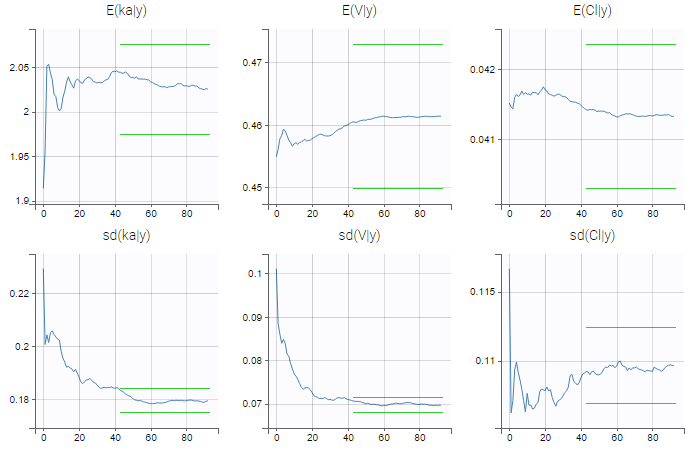

- computing the conditional modes, sample from the conditional distribution to compute the conditional means and the conditional standard deviations of the individual parameters, using the Hastings-Metropolis algorithm

- estimating standard errors for the maximum likelihood estimator

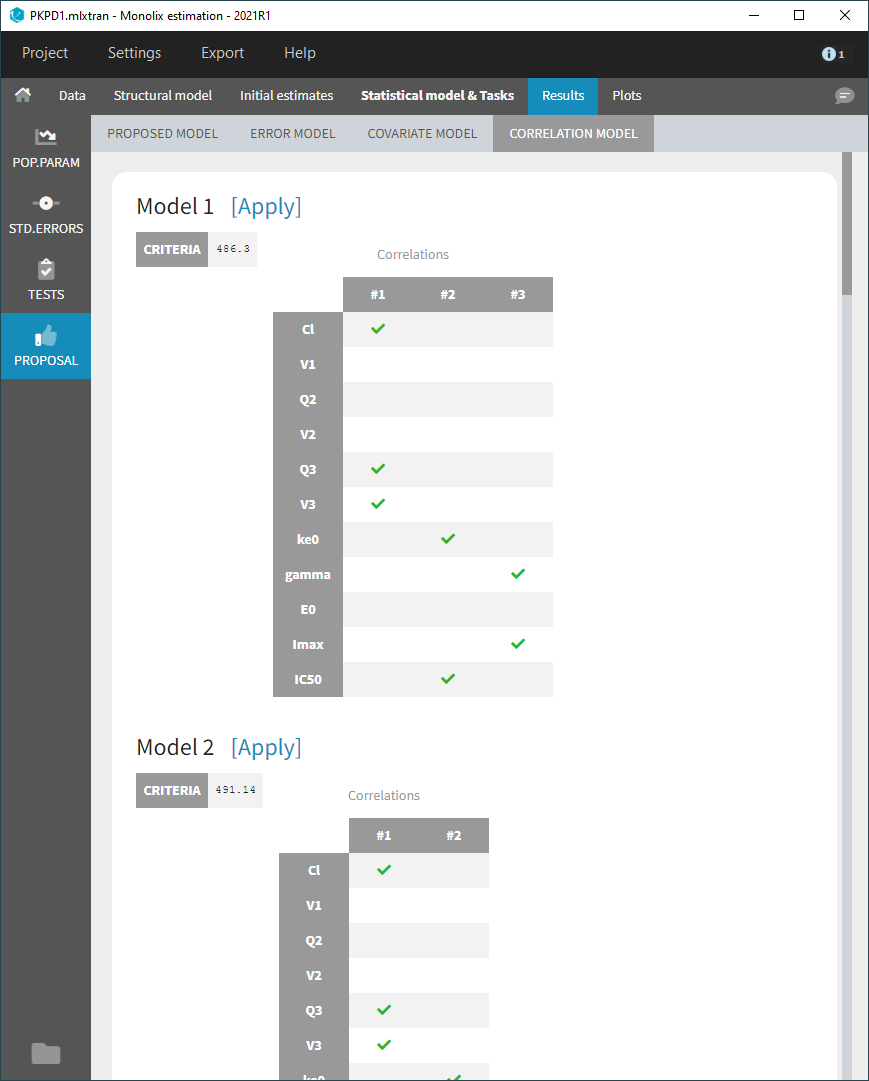

- Model selection and diagnosis

- comparing several models using some information criteria (AIC, BIC)

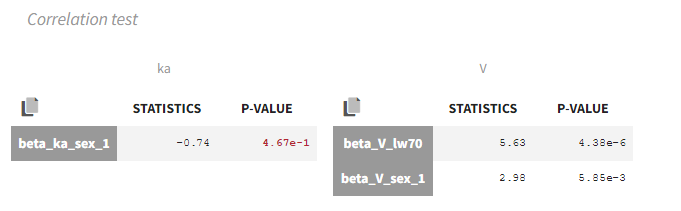

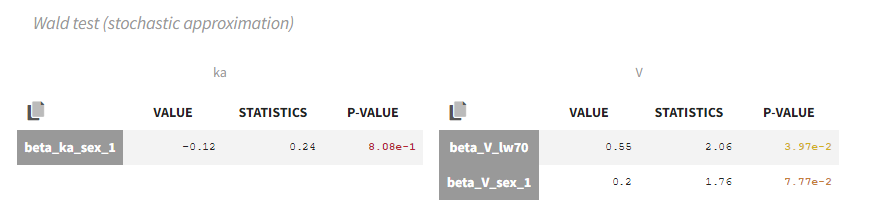

- testing parameters using the Wald Test

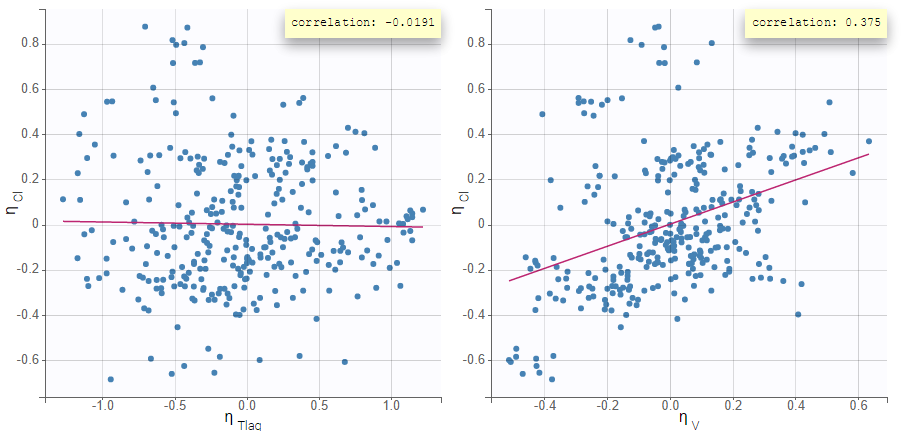

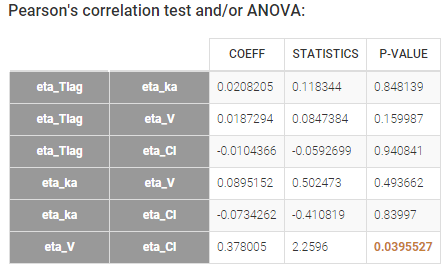

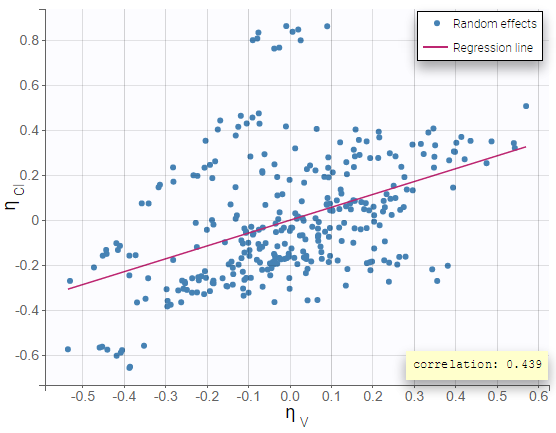

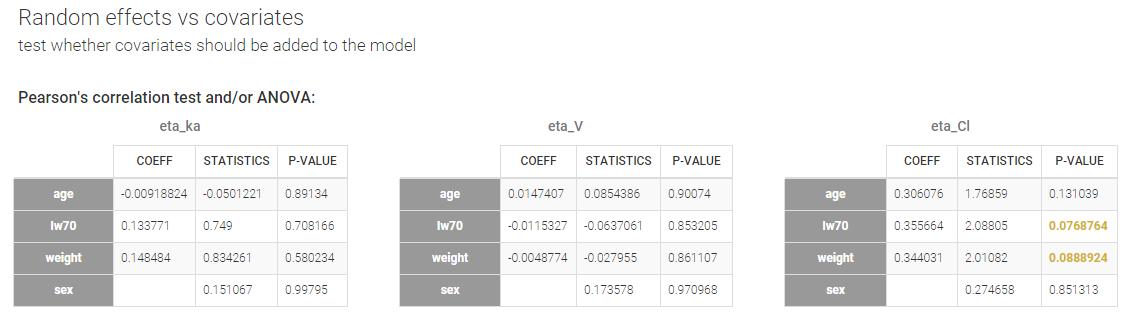

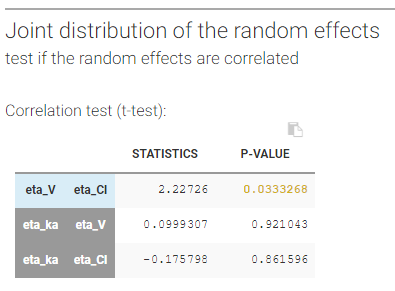

- testing correlation using Pearson’s correlation test

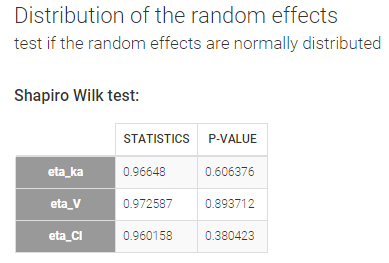

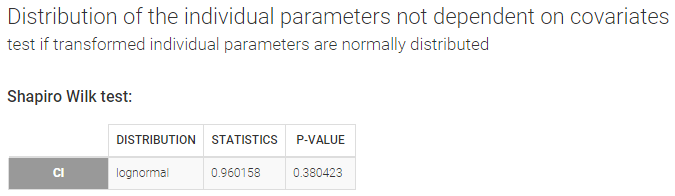

- testing normality of distribution using Shapiro’s test.

- Easy description of pharmacometric models (PK, PK-PD, discrete data) with the Mlxtran language

- Goodness of fit plots

An interface for ease of use

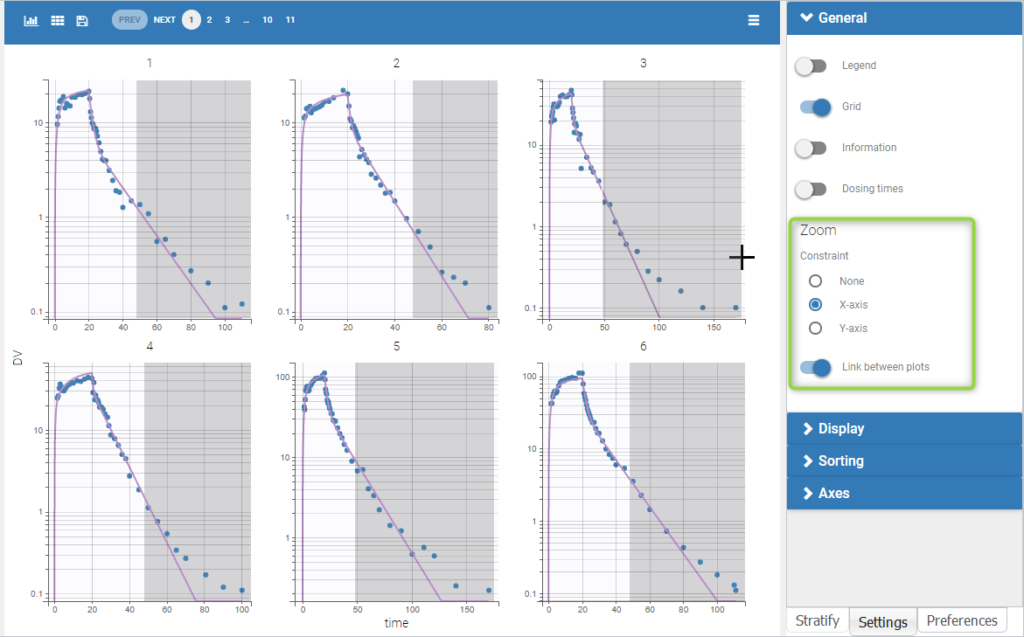

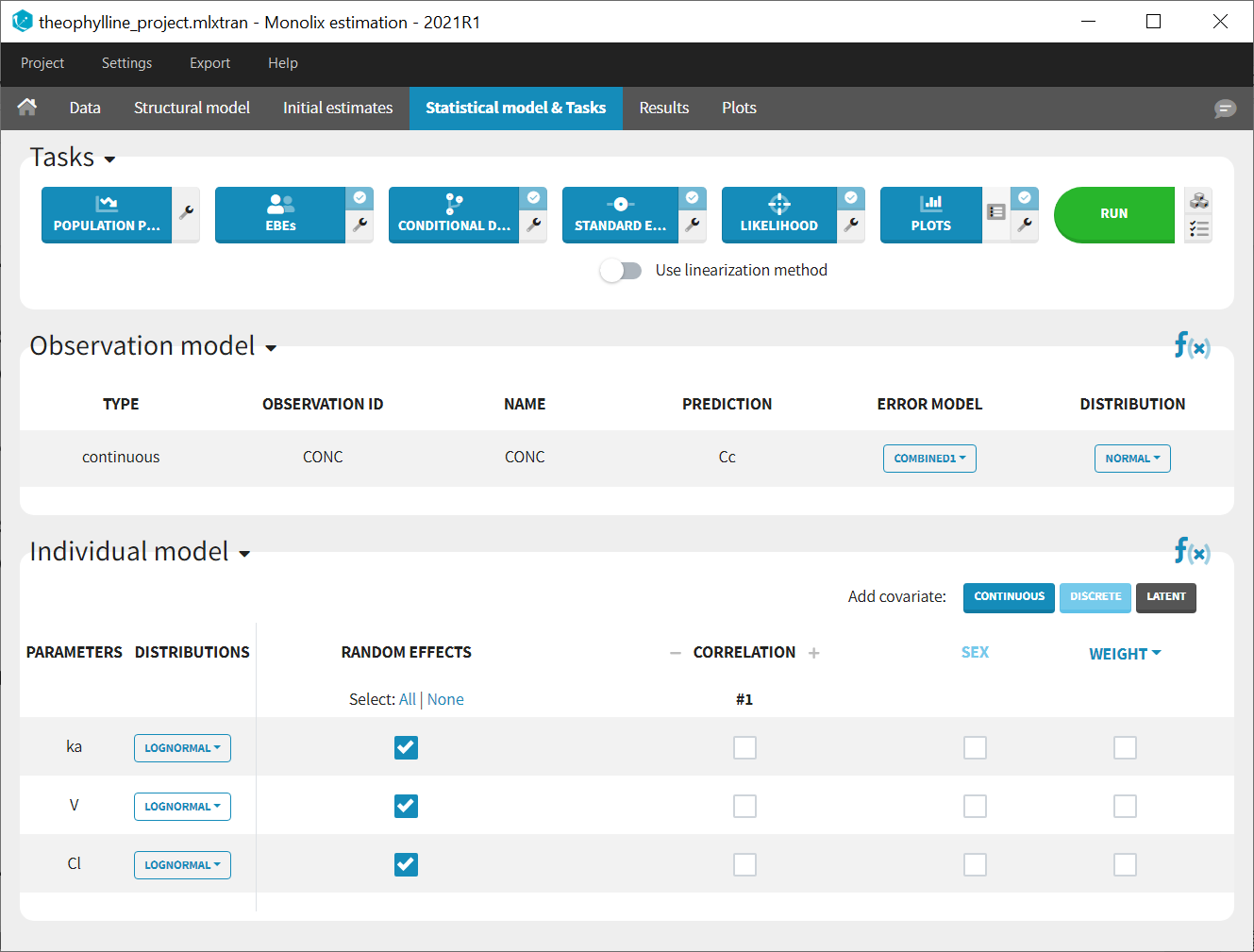

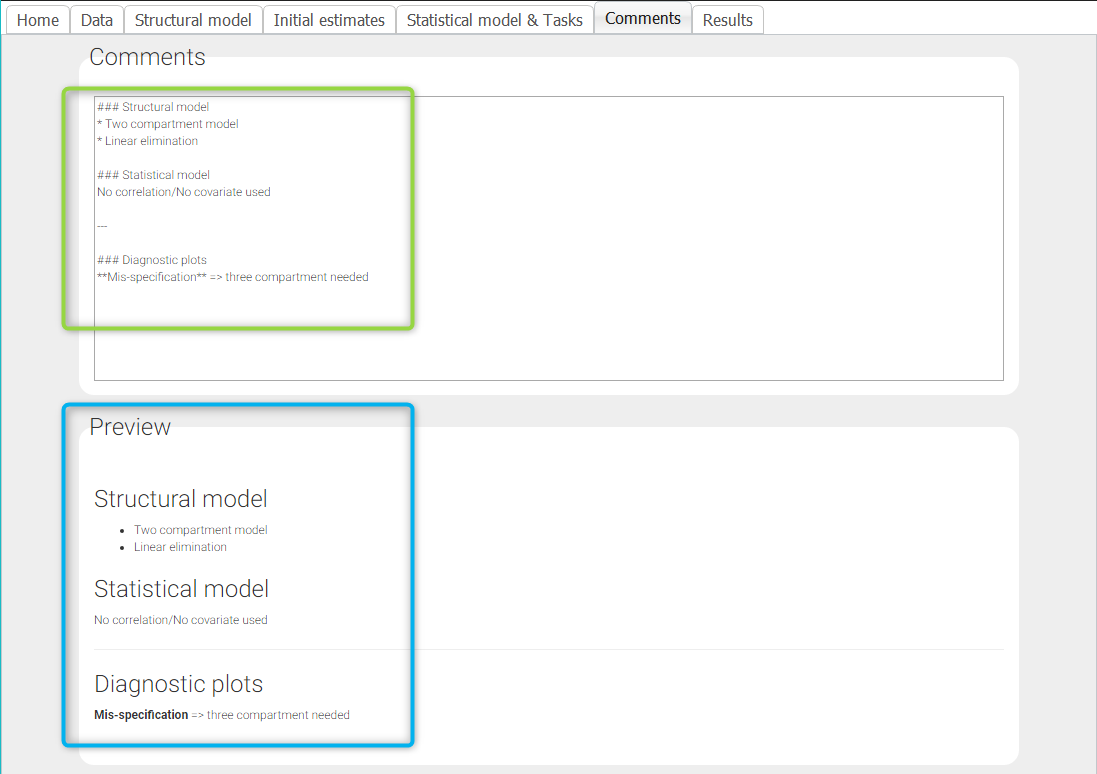

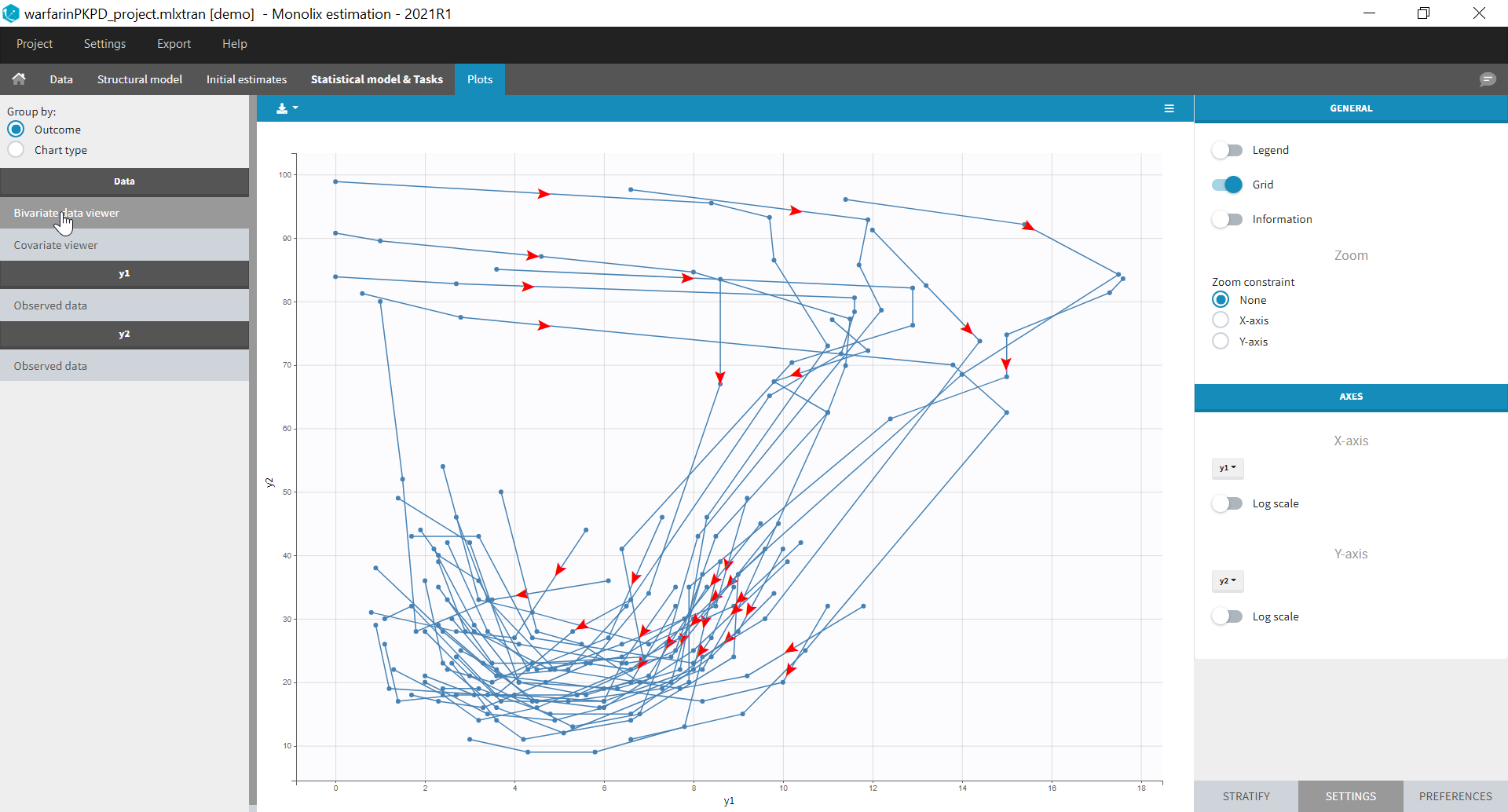

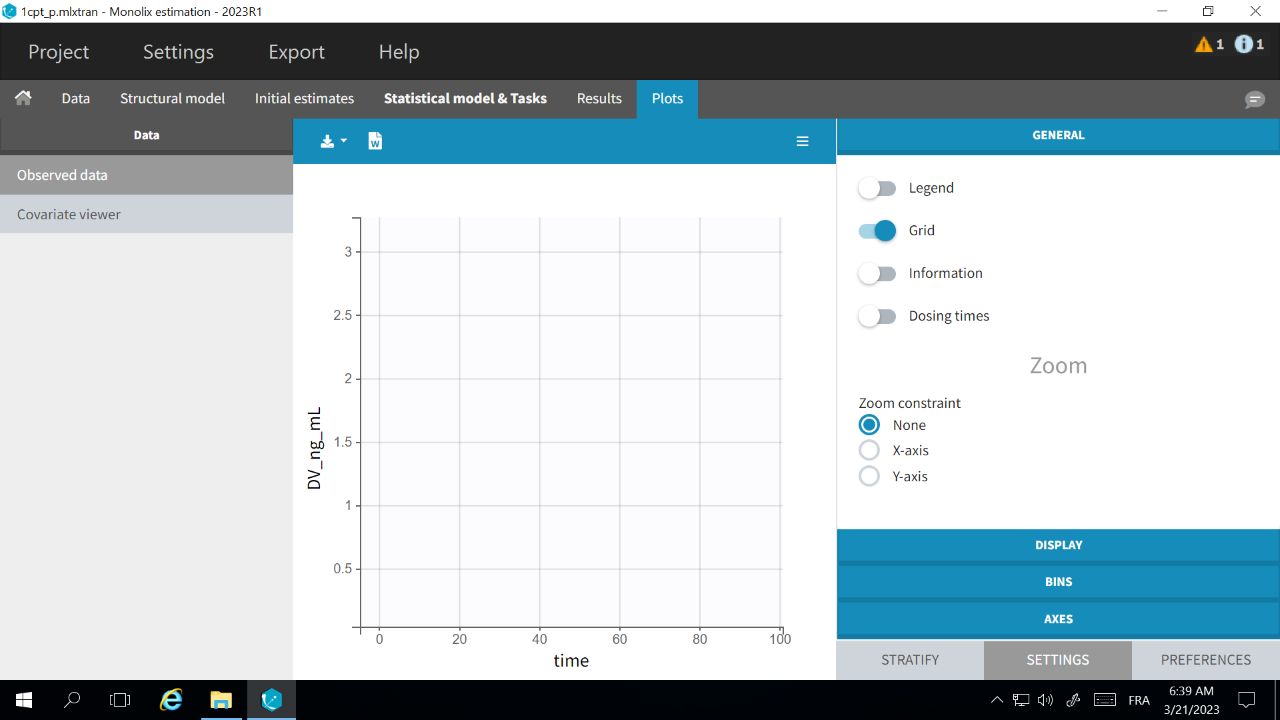

Monolix can be used either via a graphical user interface (GUI) or a command-line interface (CLI) for powerful scripting. This means less programming and more focus on exploring models and pharmacology to deliver in time. The interface is depicted as follows:

The GUI consists of 7 tabs.

- Welcome

- Data

- Structural model

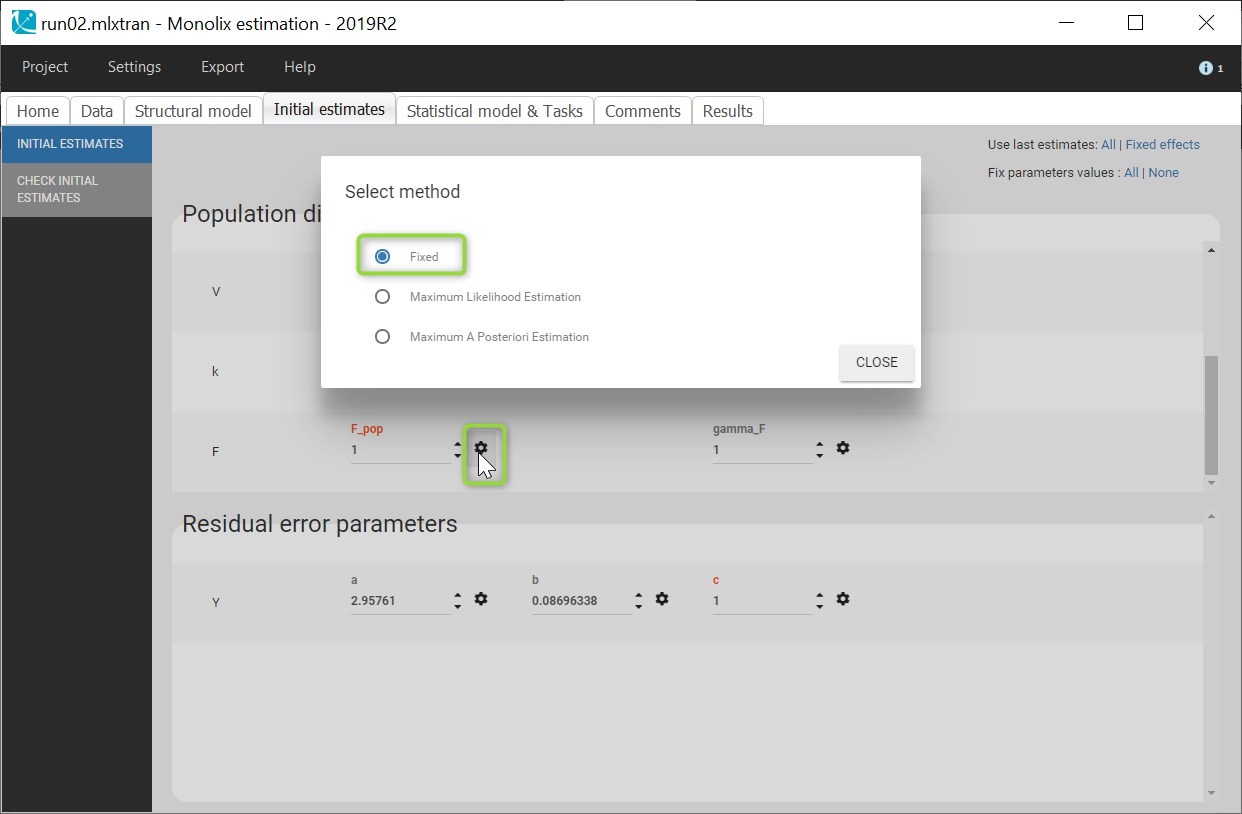

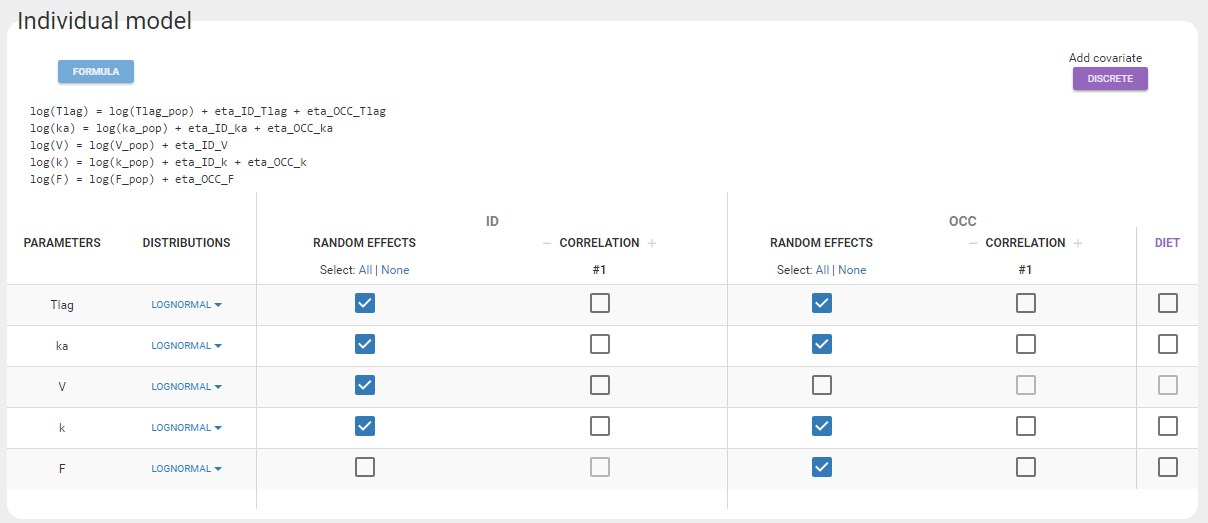

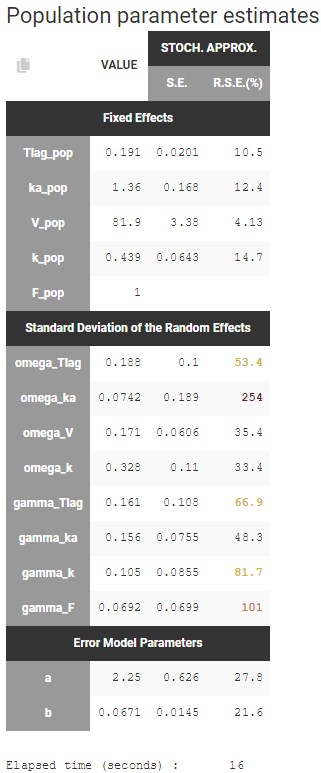

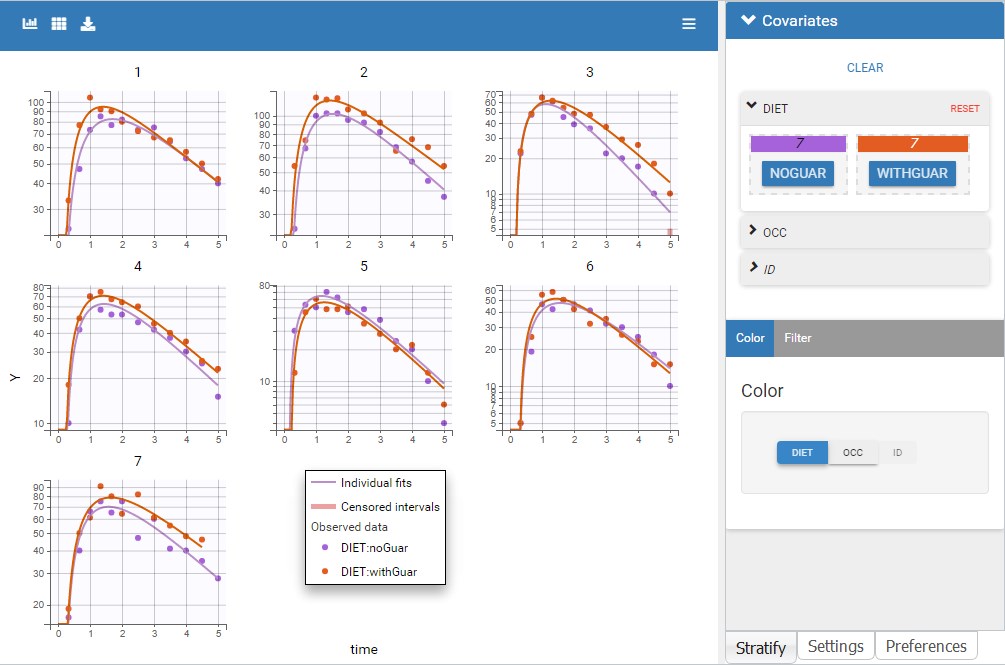

- Initial estimates

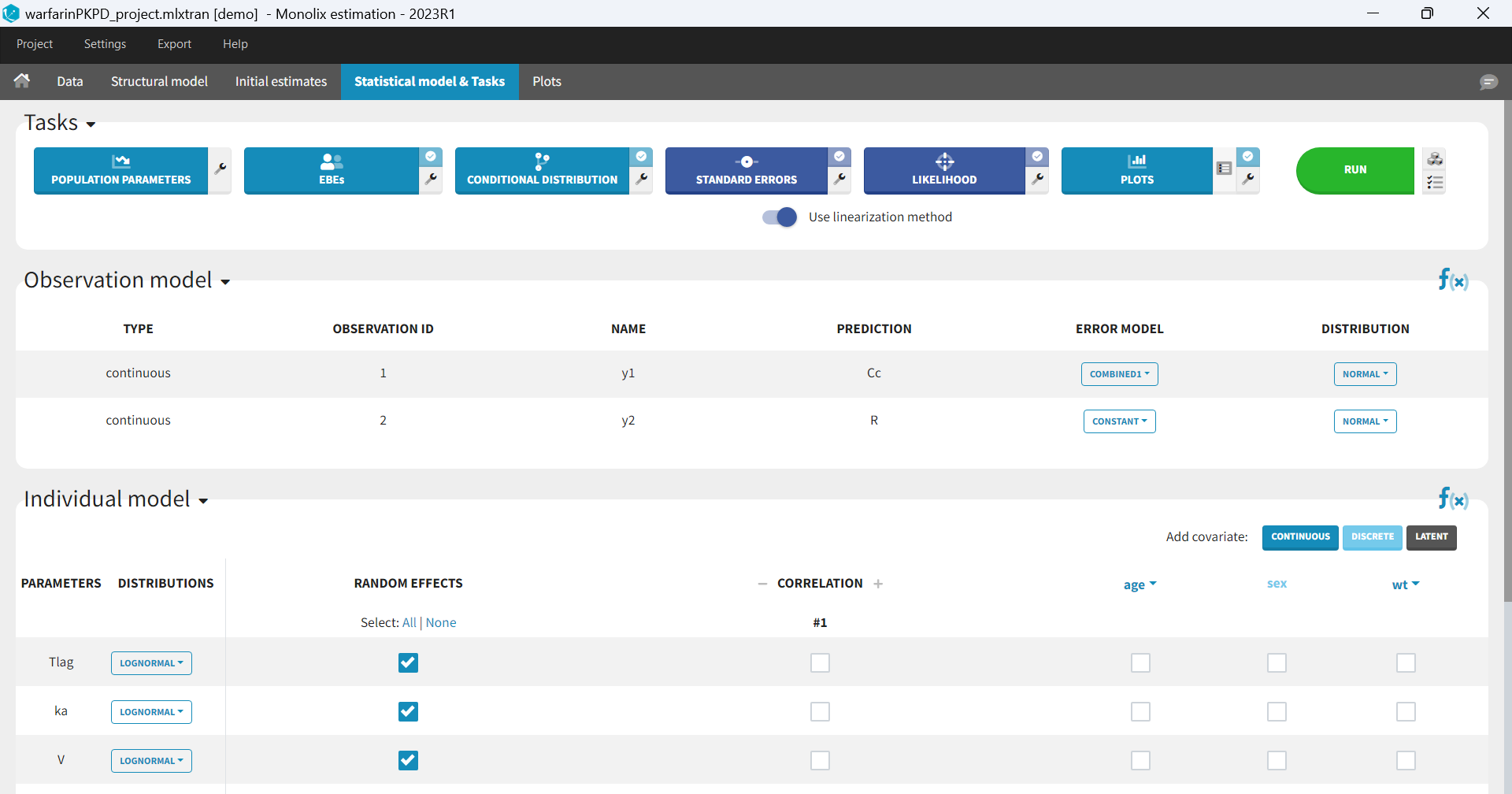

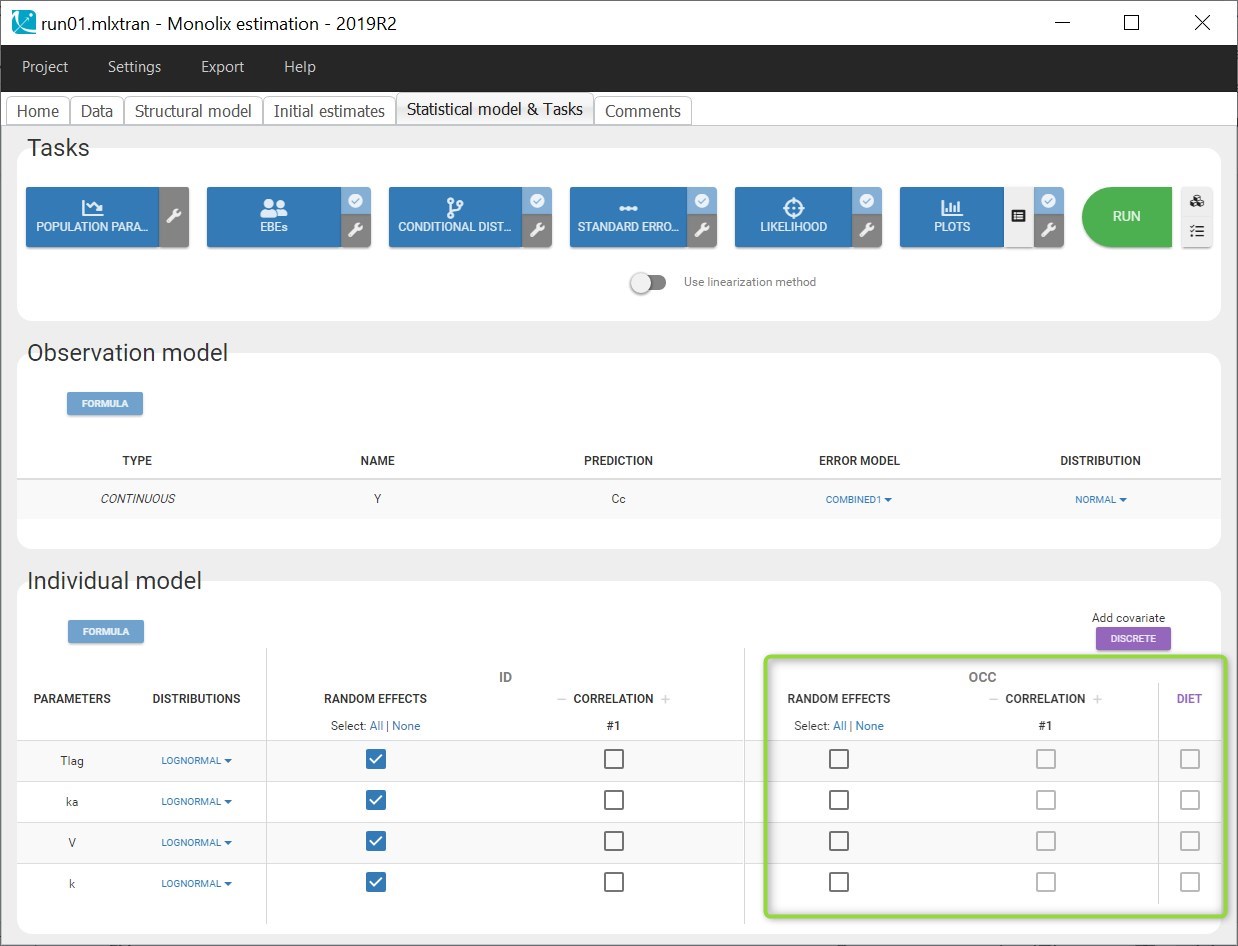

- Tasks and statistical model

- Results

- Plots

Each of these tabs refer to a specific section on this website. An advanced description of available plots is also provided.

2.Data

2.1.Defining a data set

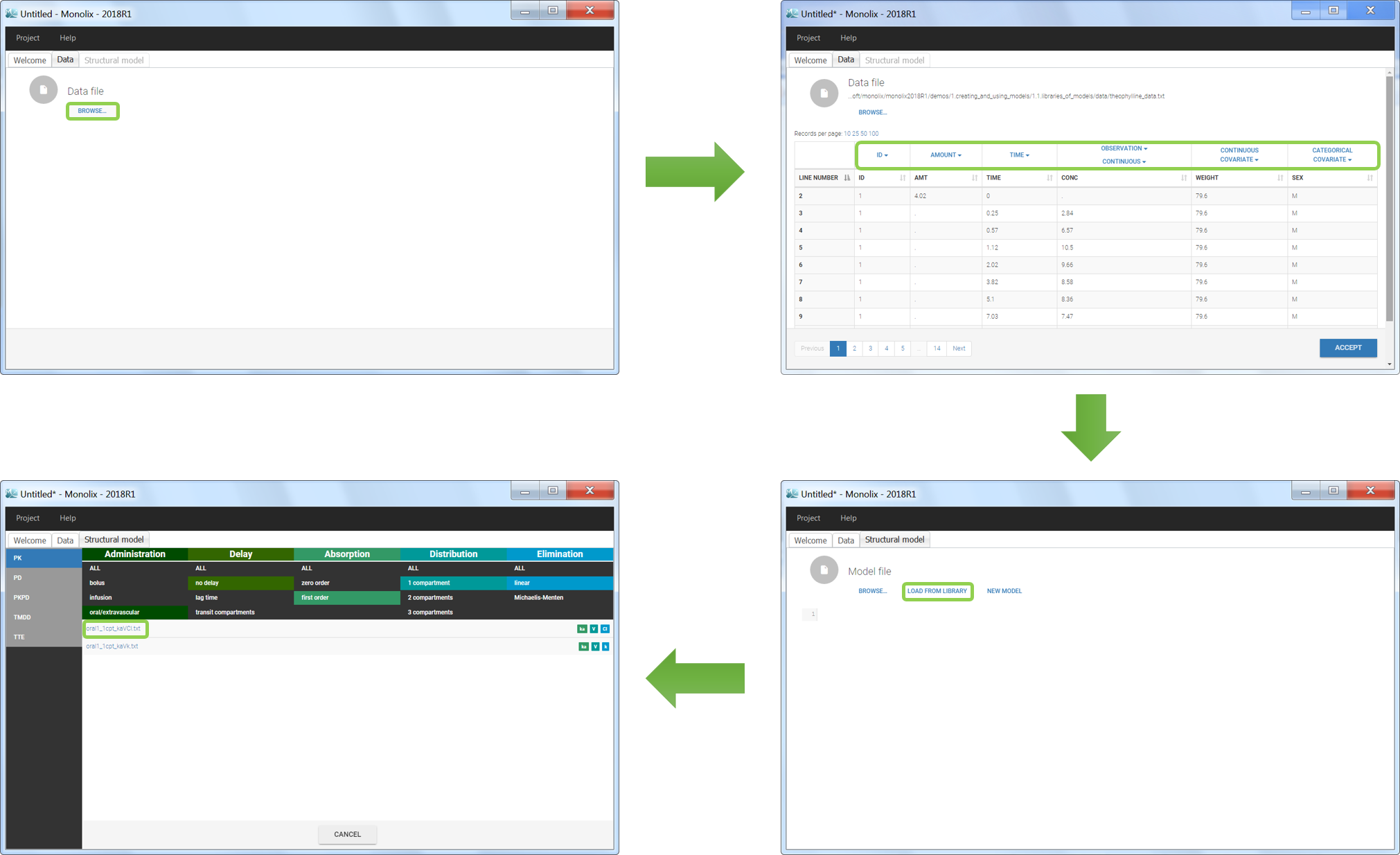

To start a new Monolix project, you need to define a dataset by loading a file in the Data tab, and load a model in the structural model tab. The project can be saved only after defining the data and the model.

Supported file types: Supported file types include .txt, .csv, and .tsv files. Starting with version 2024, additional Excel and SAS file types are supported: .xls, .xlsx, .sas2bdat, and .xpt files in addition to .txt, .csv, and .tsv files.

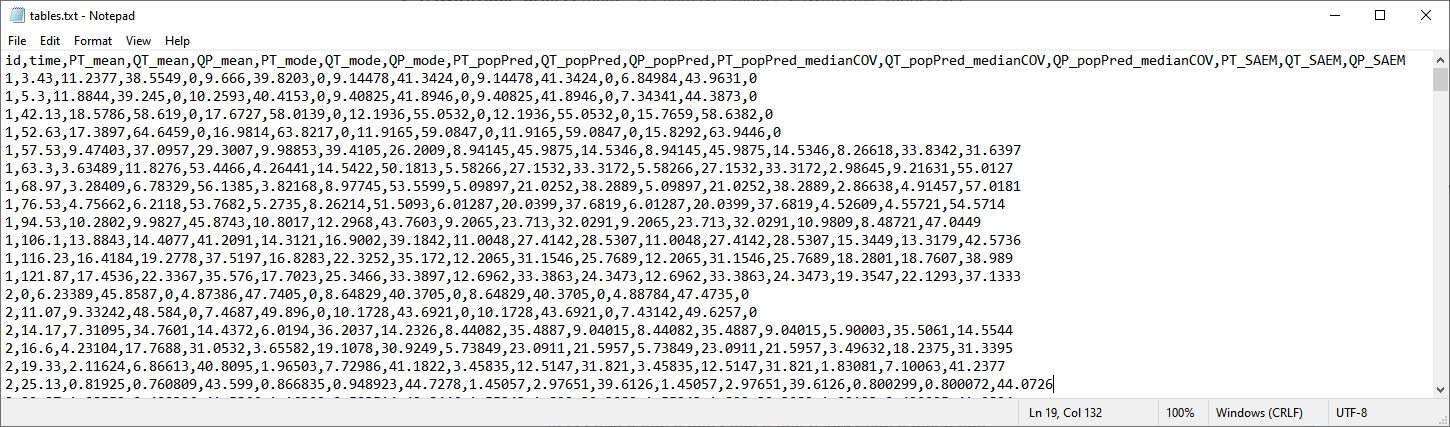

The data set format expected in the Data tab is the same as for the entire MonolixSuite, to allow smooth transitions between applications. The columns available in this format and example datasets are detailed on this page. Briefly:

- Each line corresponds to one individual and one time point

- Each line can include a single measurement (also called observation), or a dose amount (or both a measurement and a dose amount)

- Dosing information should be indicated for each individual, even if it is identical for all.

Your dataset may not be originally in this format, and you may want to add information on dose amounts, limits of quantification, units, or filter part of the dataset. To do so, you should proceed in this order:

- Formatting: If needed, format your data first by loading the dataset in the Data Formatting tab. Briefly, it allows to:

- to deal with several header lines

- merge several observation columns into one

- add censoring information based on tags in the observation column

- add treatment information manually or from external sources

- add more columns based on another file

- Loading a new data set: If the data is already in the right format, load it directly in the Data tab (otherwise use the formatted dataset created by data formatting).

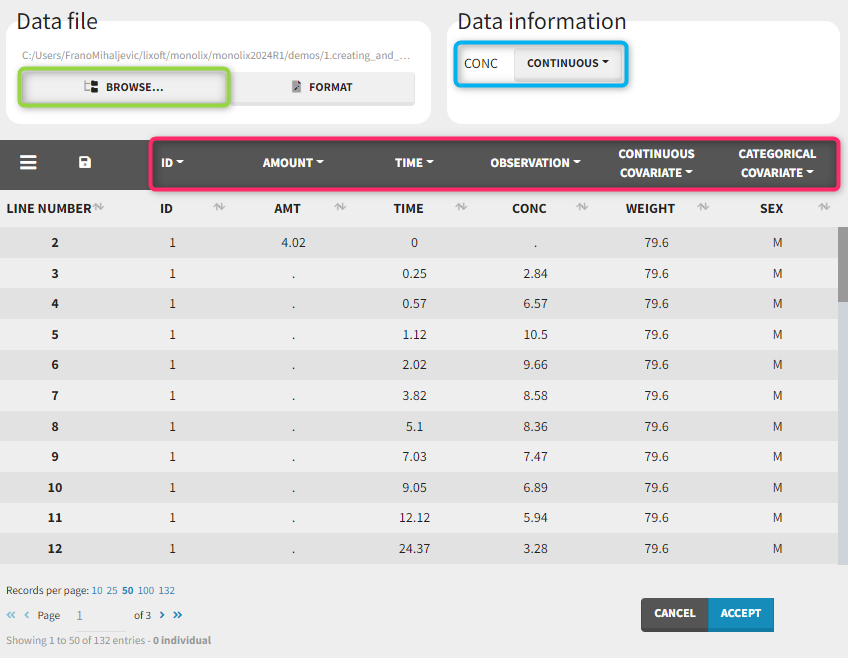

- Observation types: Specify if the observation is of type continuous, count/categorical or event.

- Labeling: label the columns not recognized automatically to indicate their type and click on ACCEPT.

- Filtering: If needed, filter your dataset to use only part of it in the Filters tab

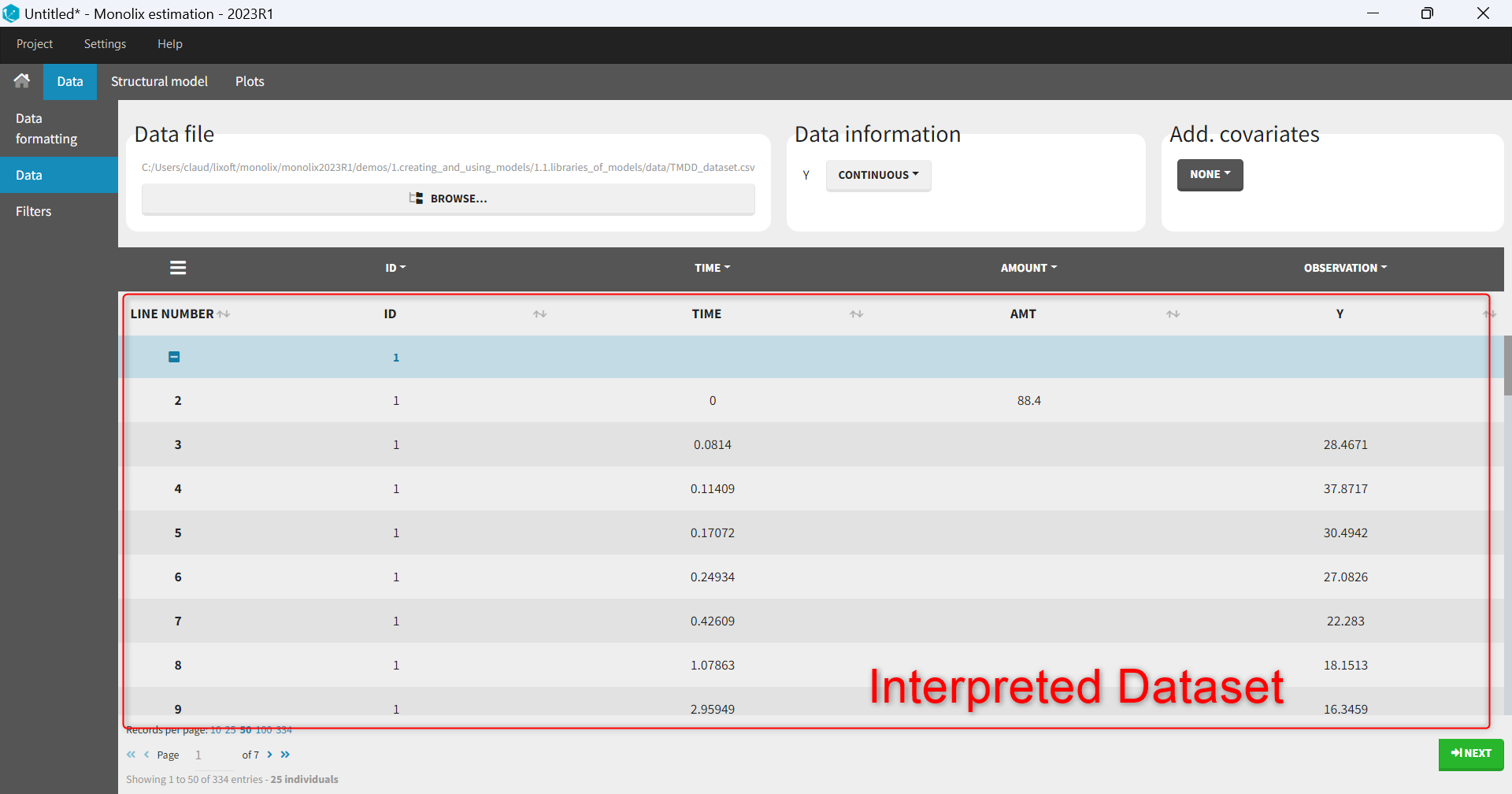

- Explore: The interpreted dataset is displayed in Data, and Plots and covariate statistics are generated.

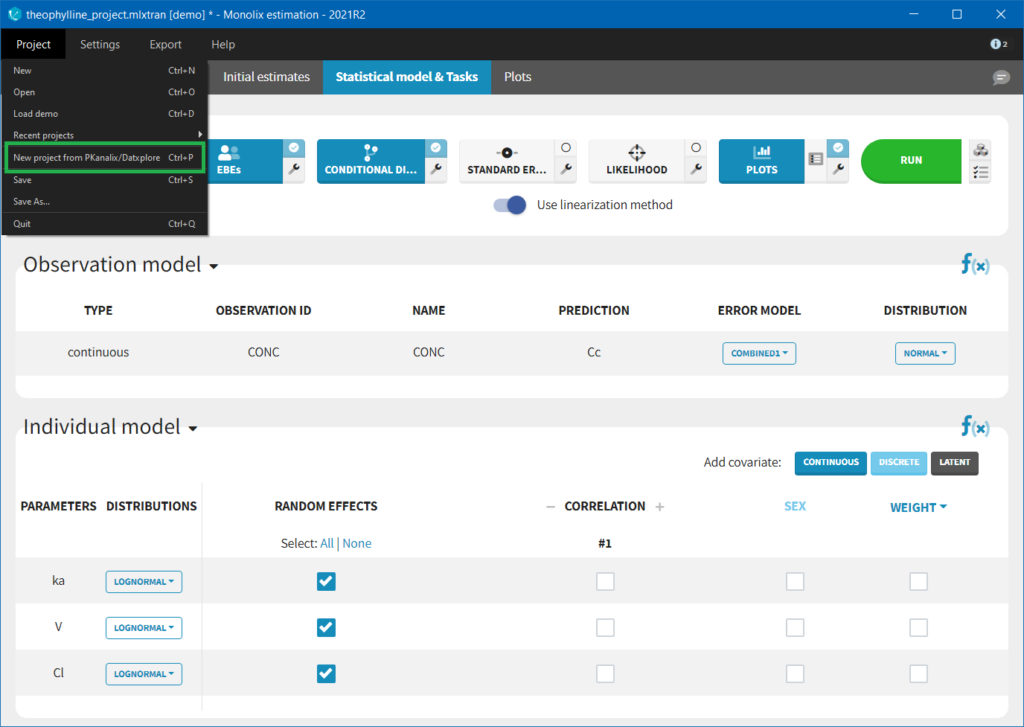

If you have already defined a dataset in Datxplore or in PKanalix, you can skip all those steps in Monolix and create a new project by importing a project from Datxplore or PKanalix.

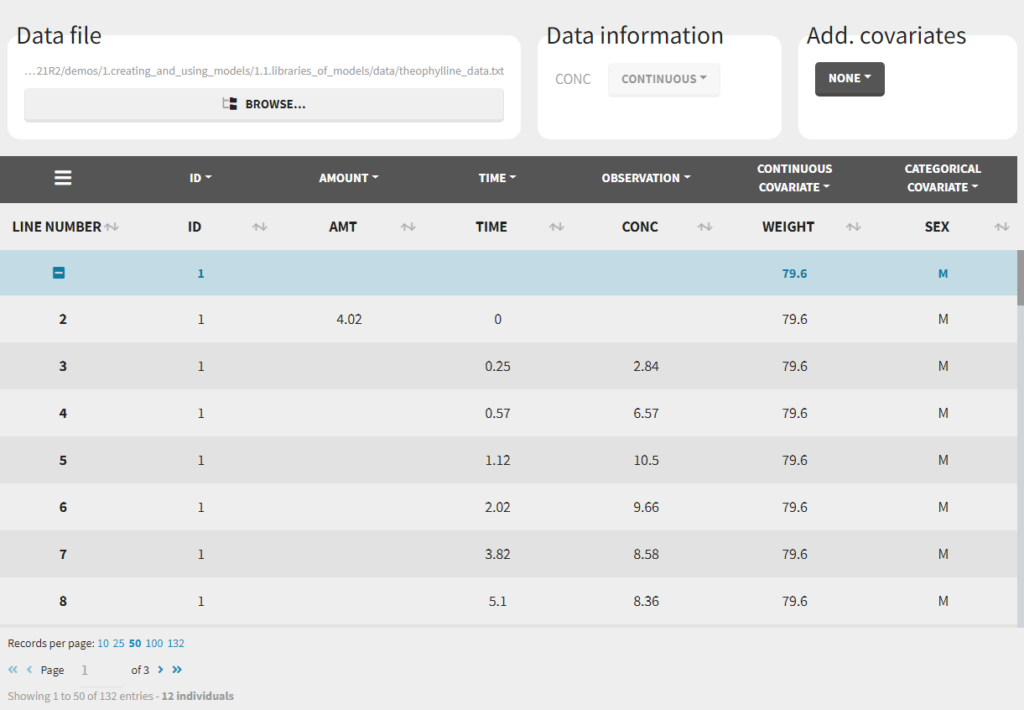

Loading a new data set

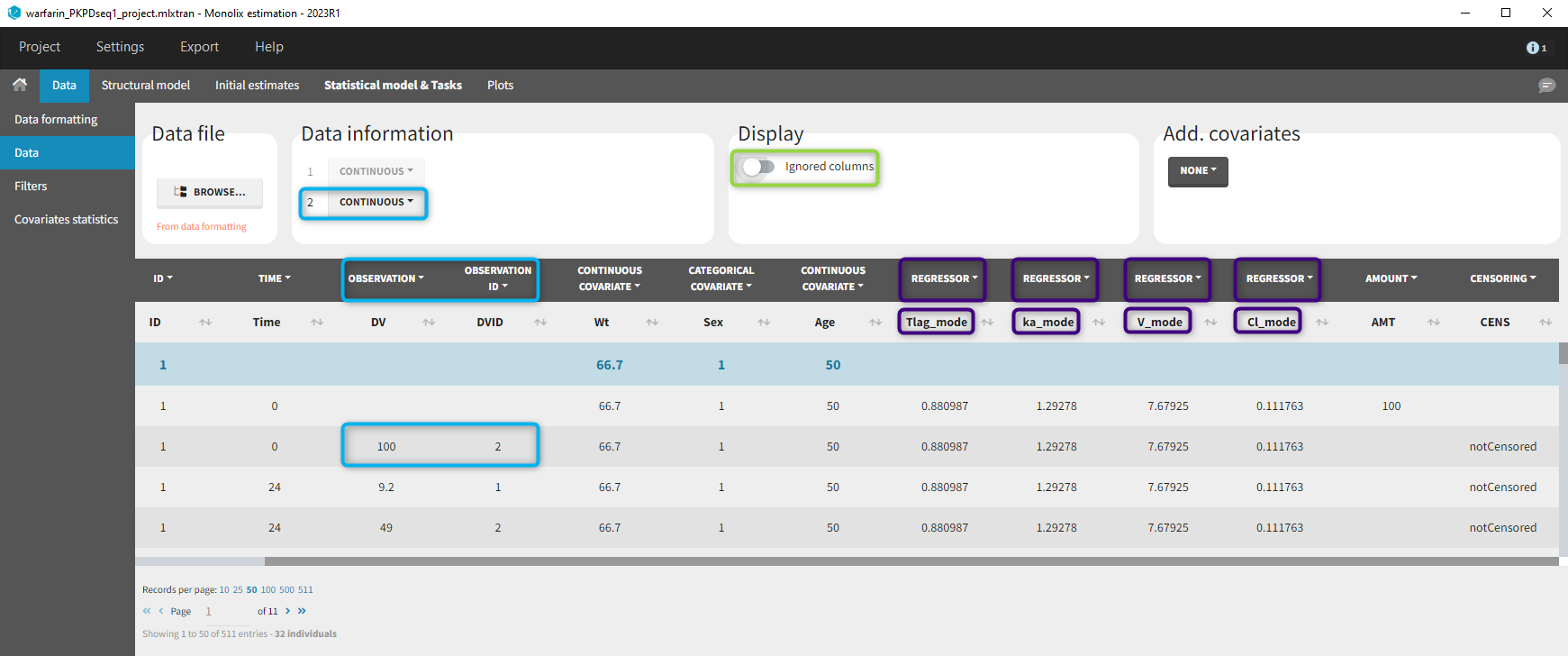

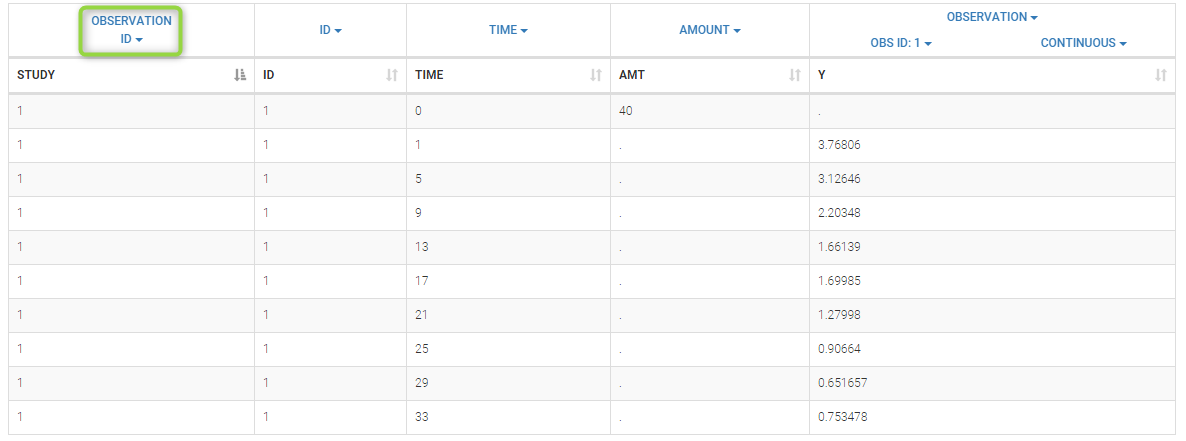

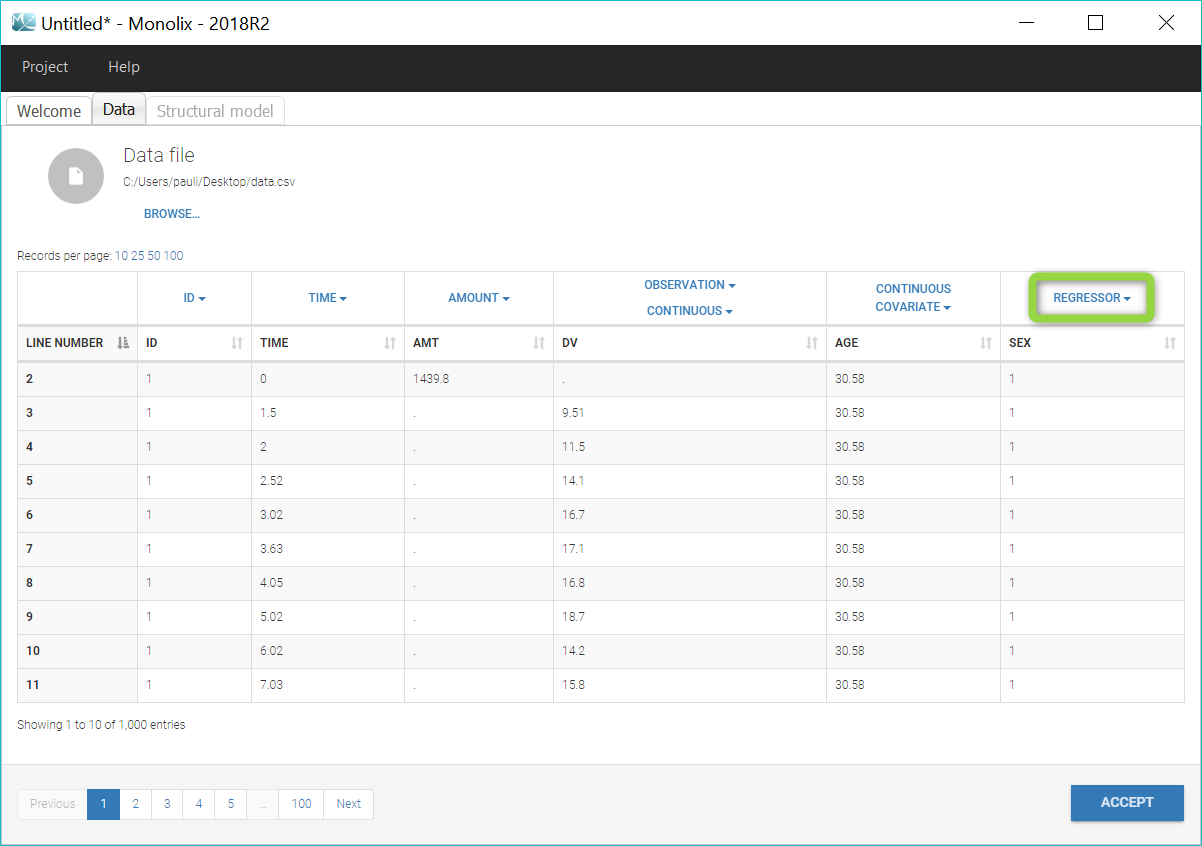

To load a new data set, you have to go to “Browse” your data set (green frame), tag all the columns (purple frame), define the observation types in Data Information (blue frame), and click on the blue button ACCEPT as on the following. If the dataset does not follow a formatting rule, the dataset will not be accepted, but errors will guide you to find what is missing and could be added by data formatting.

Observation types

There are three types of observations:

- continuous: The observation is continuous and can take any value within a range. For example, a concentration is a continuous observation.

- count/categorical: The observation values can take values only in a finite categorical space. For example, the observation can be a categorical observation (an effect can be observed as “low”, “medium”, or “high”) or a count observation over a defined time (the number of epileptic crisis in a week).

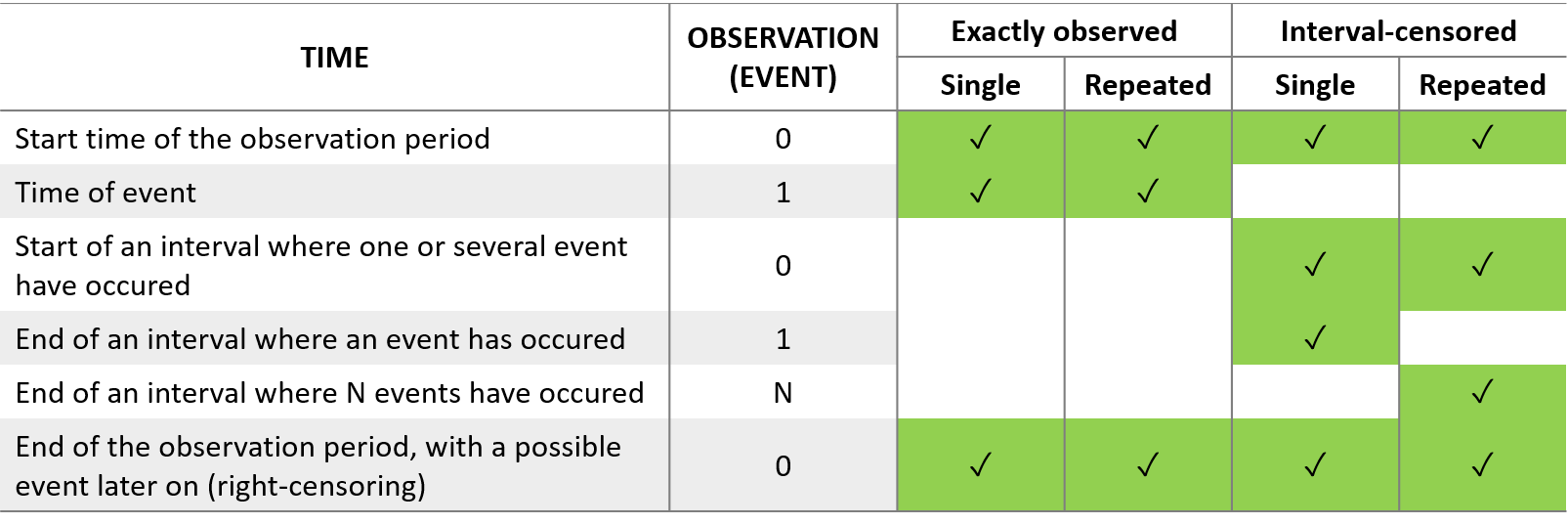

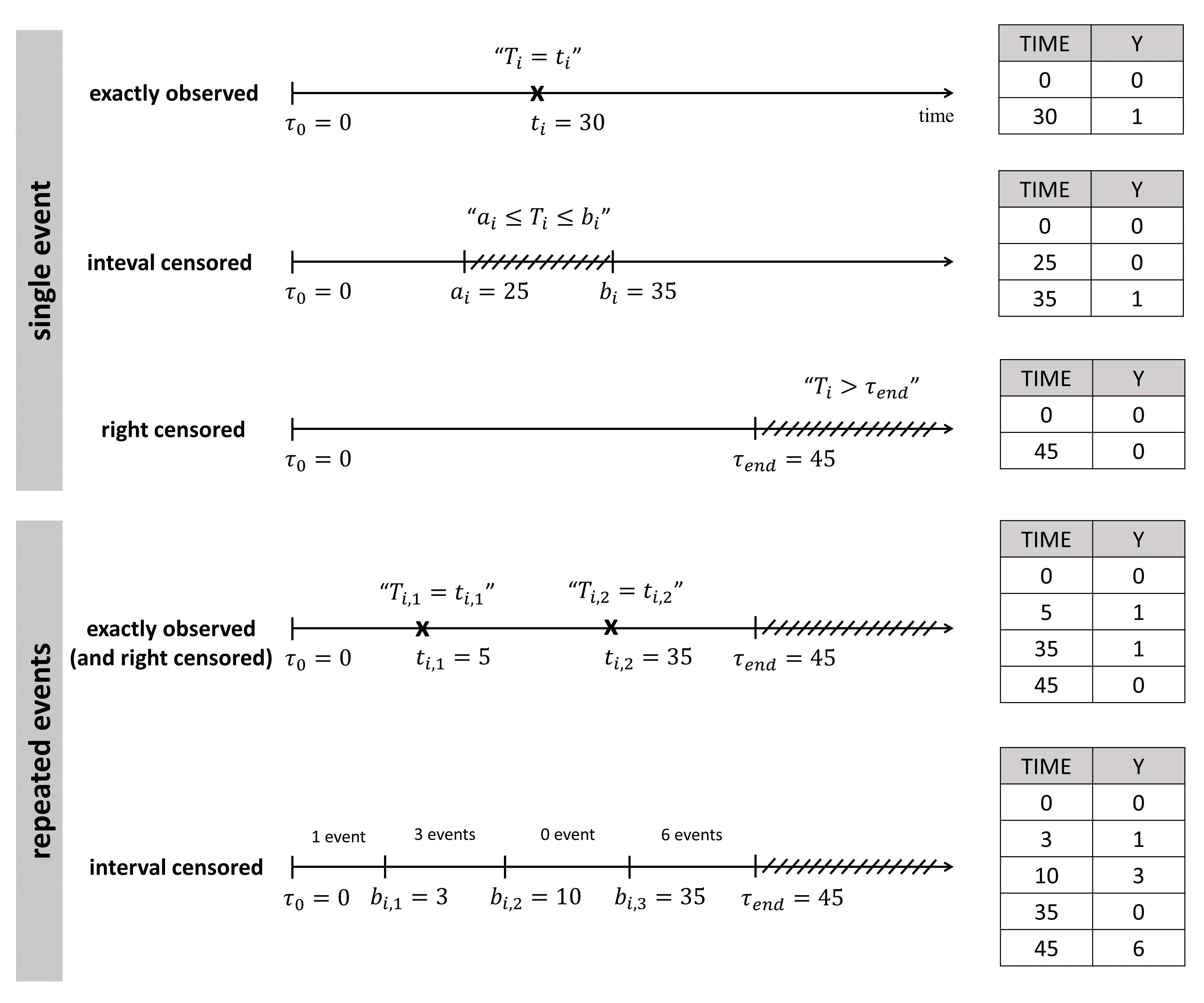

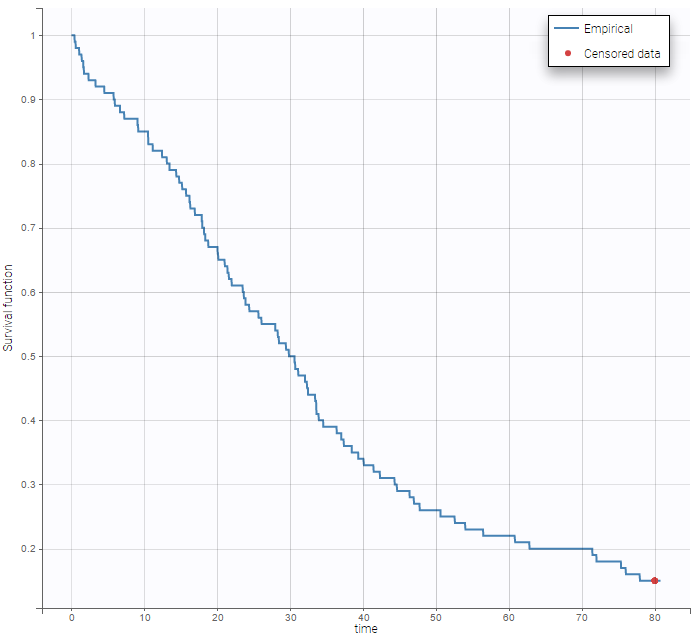

- event: The observation is an event, for example the time of death.

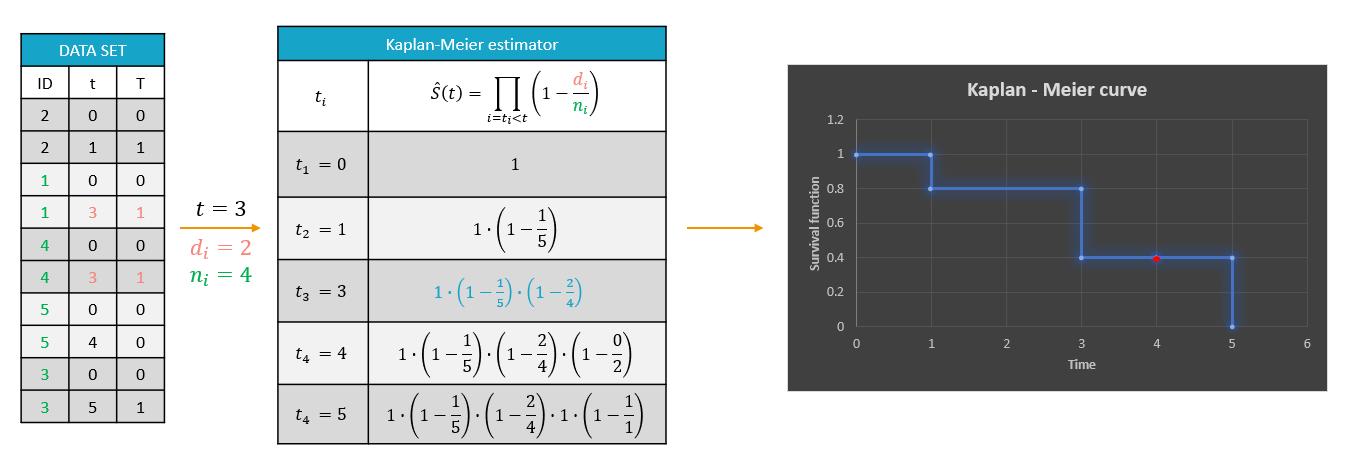

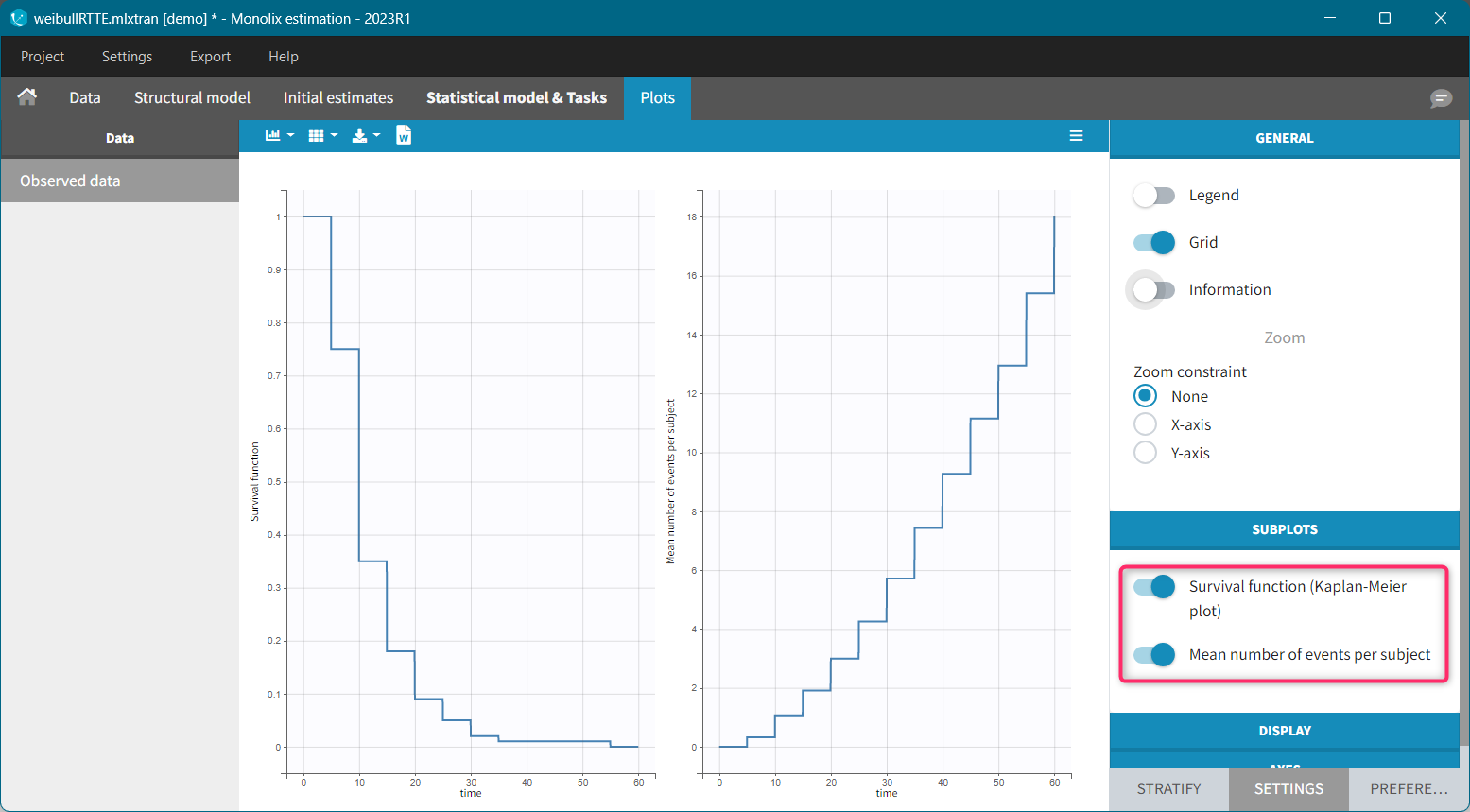

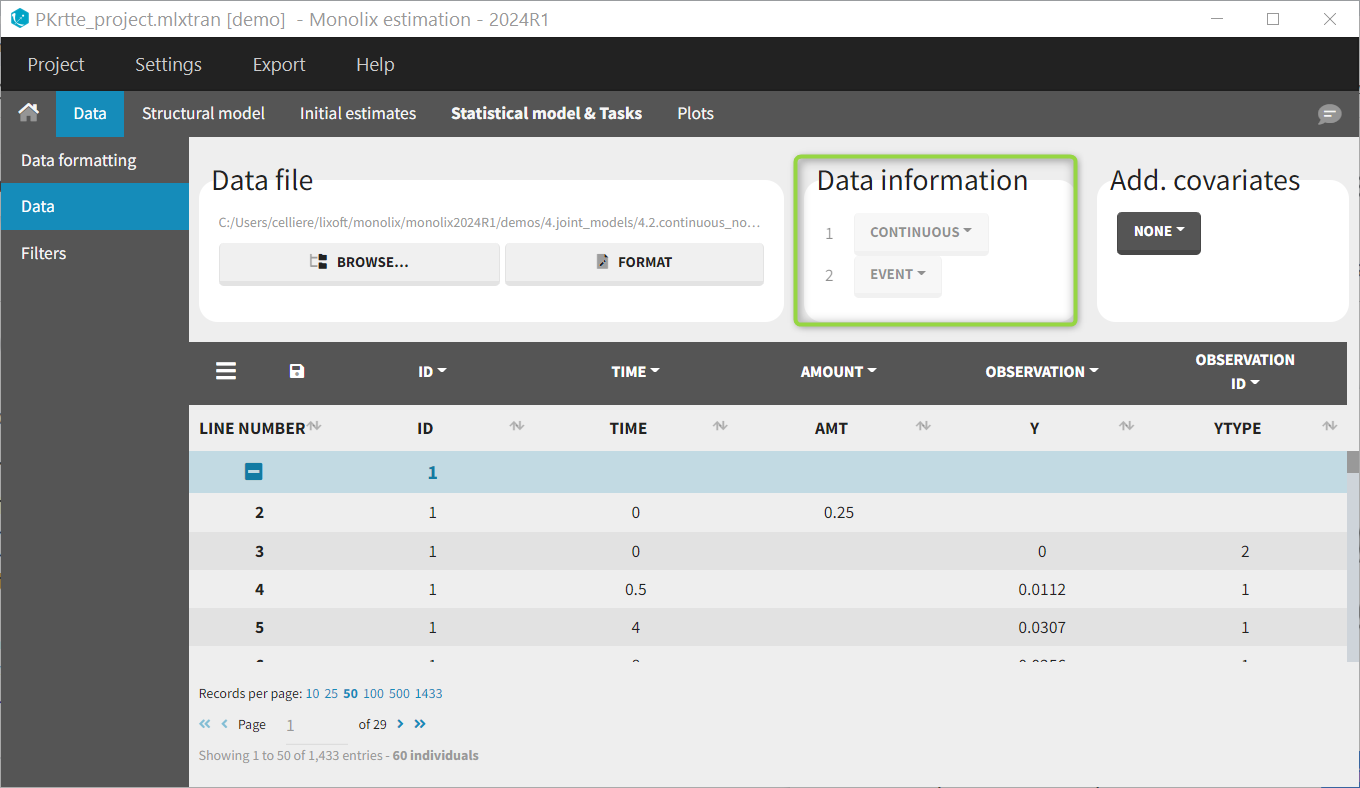

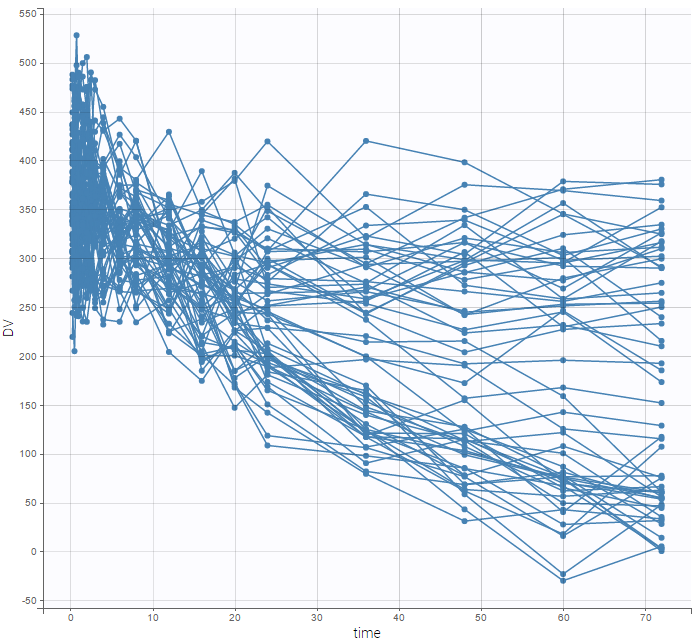

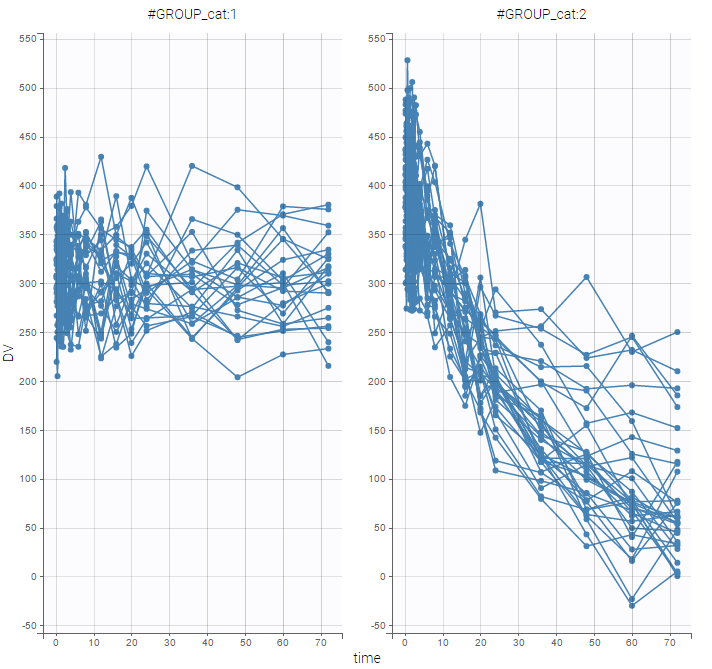

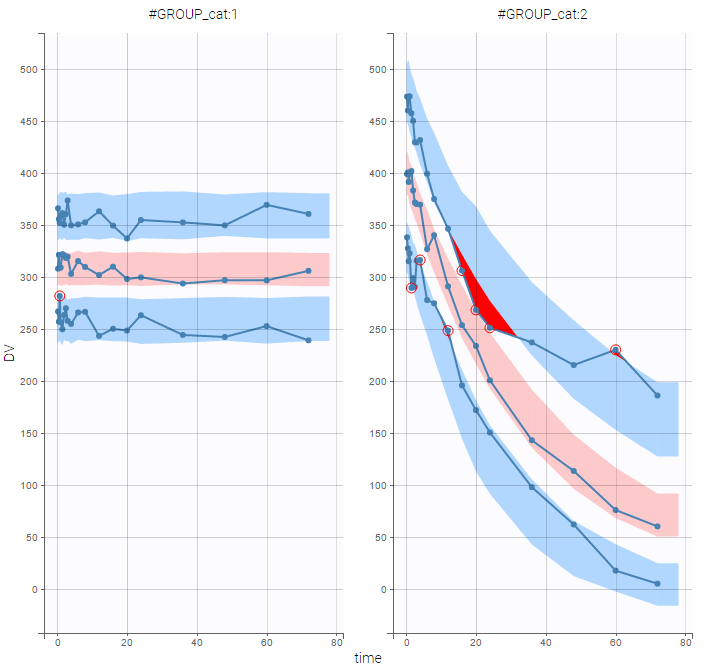

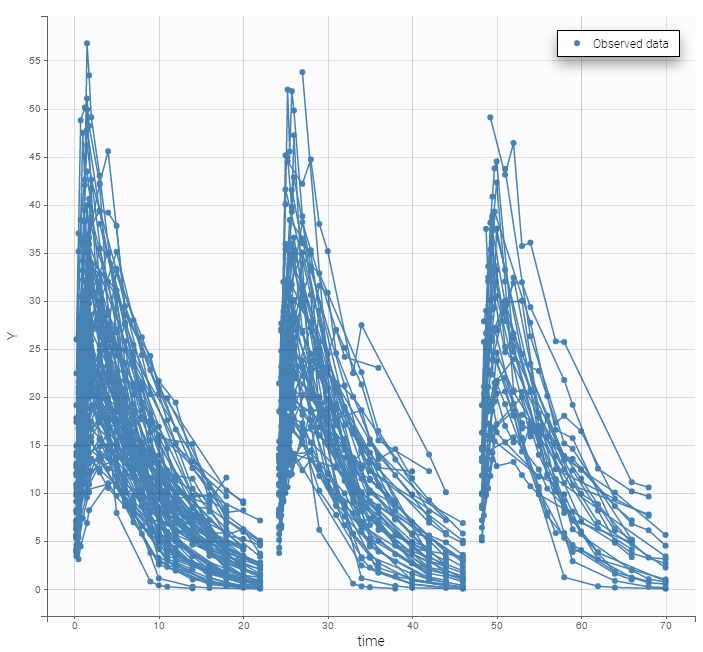

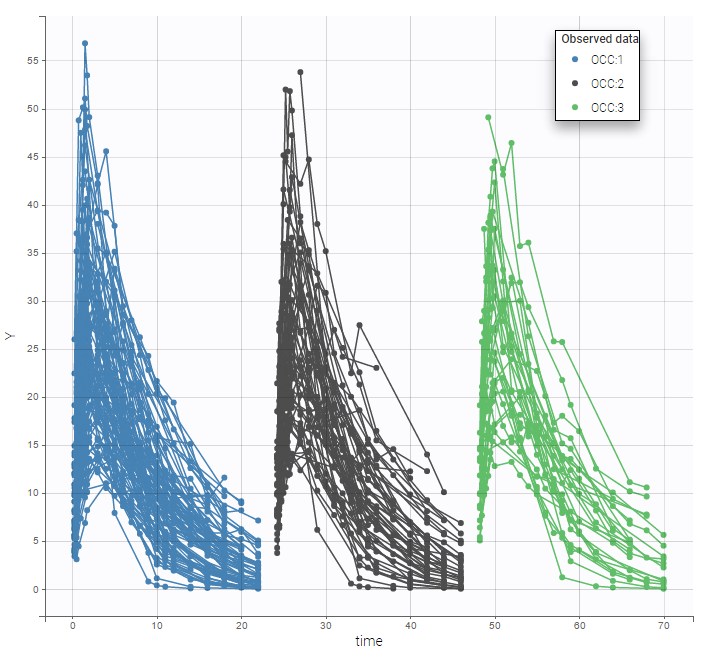

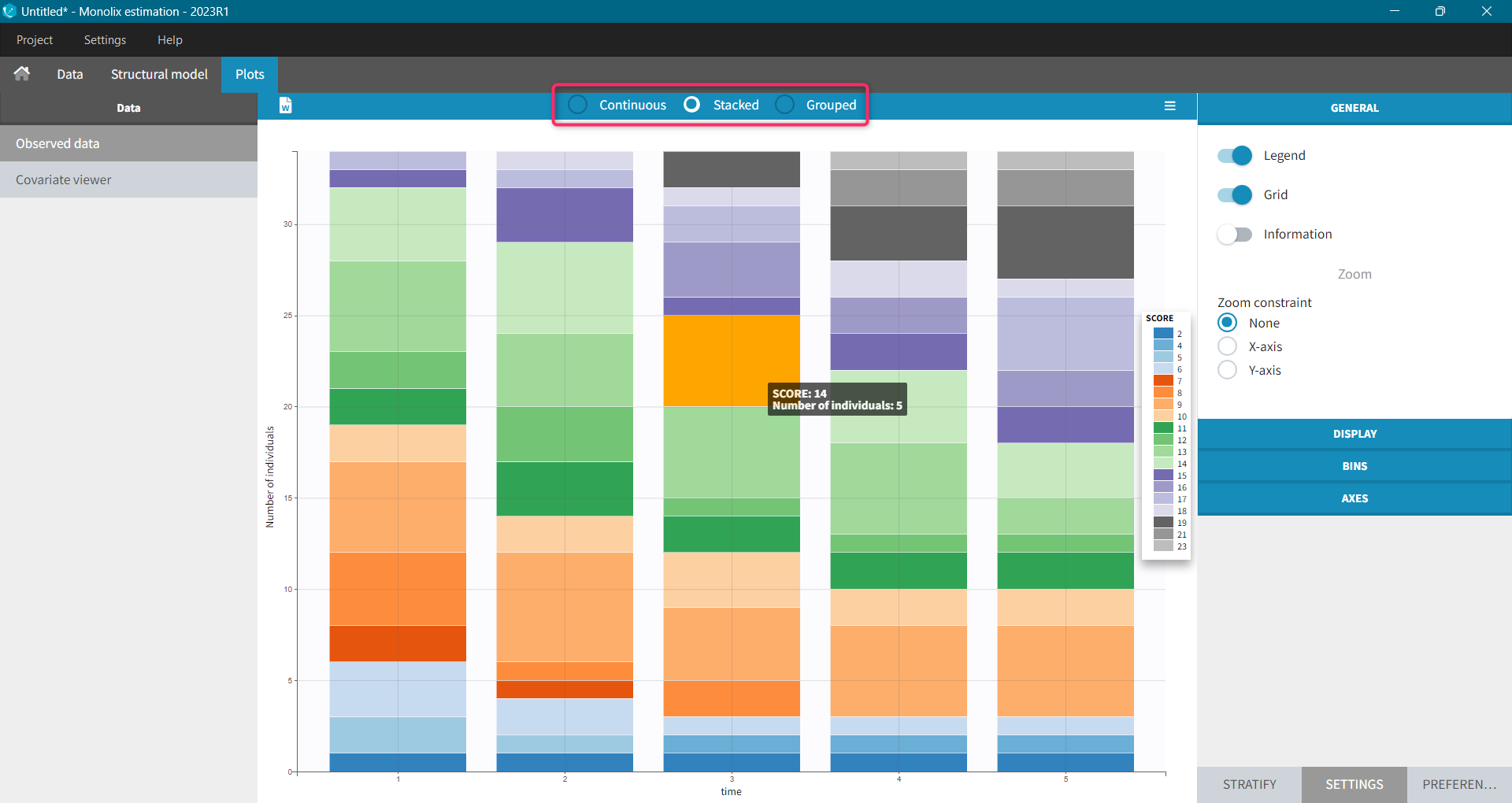

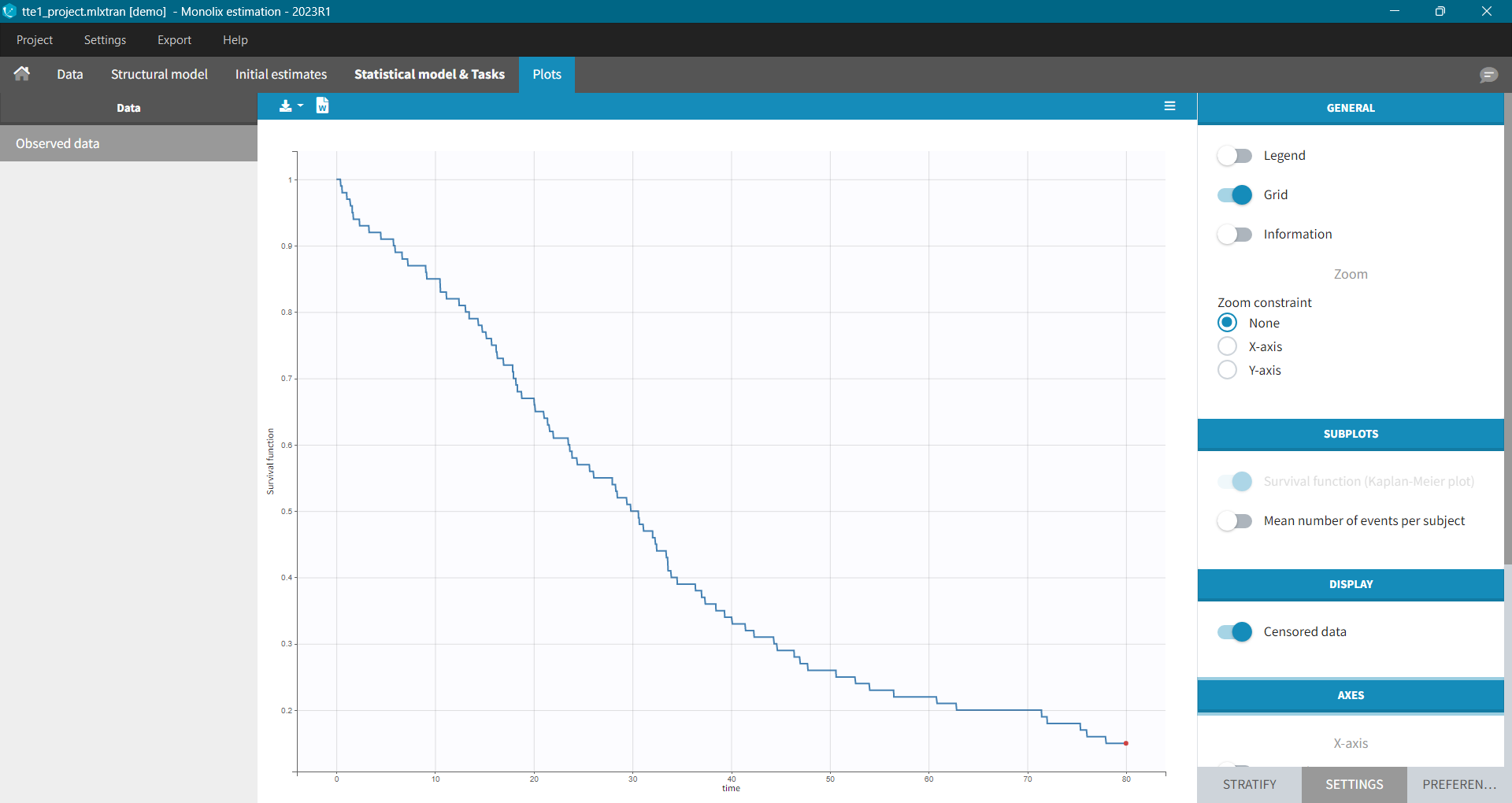

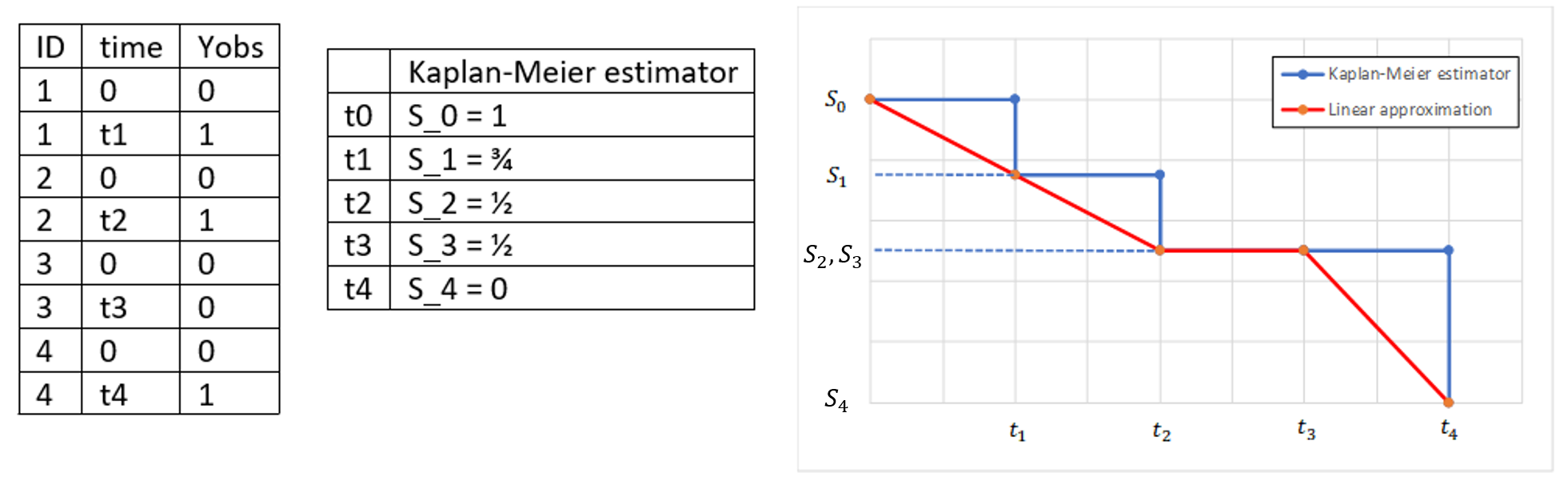

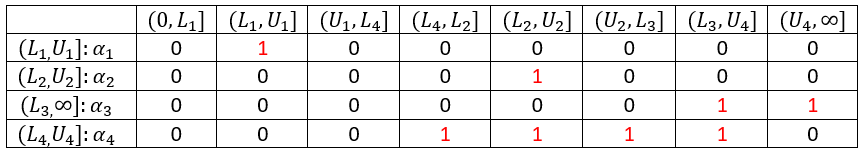

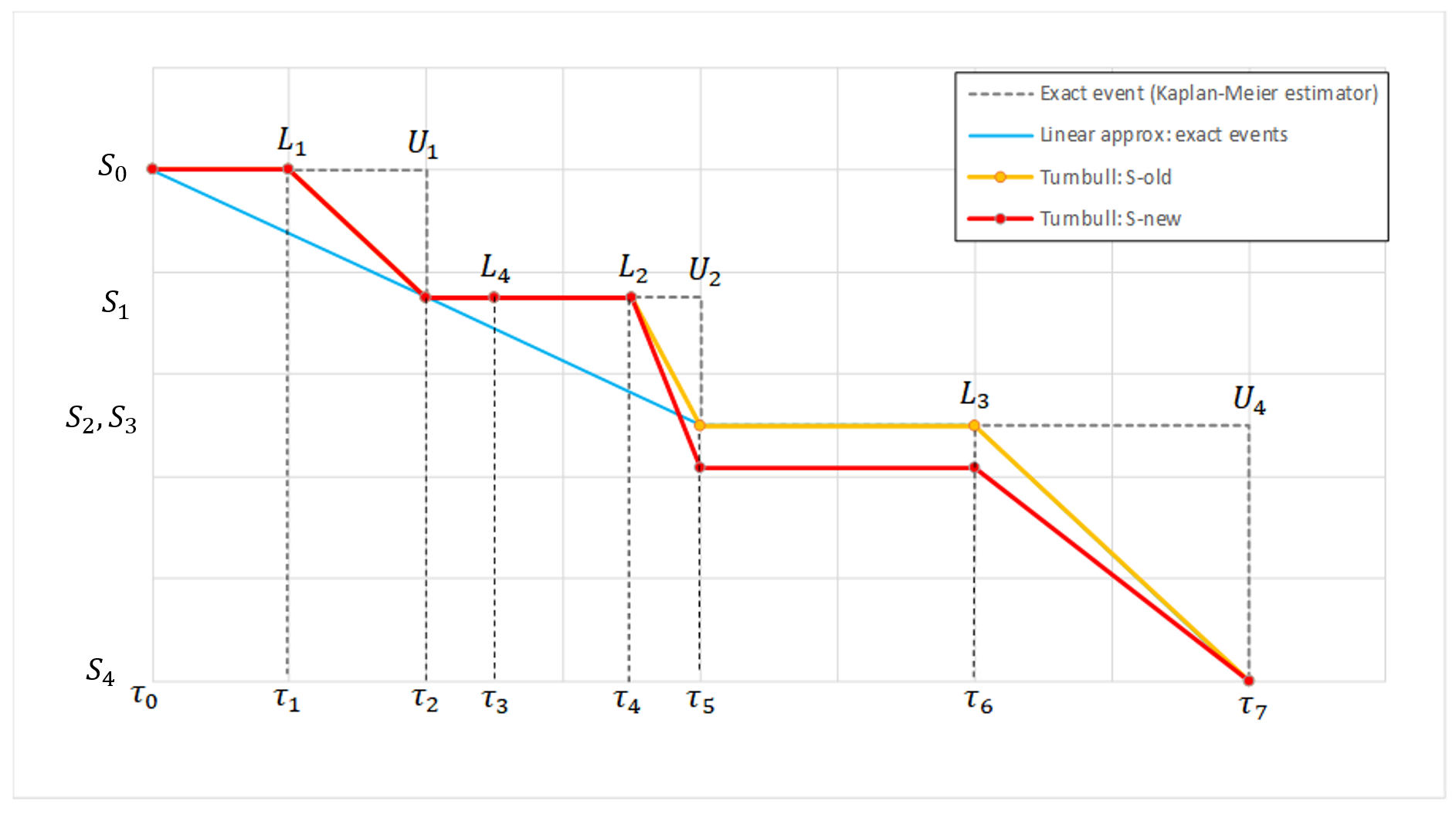

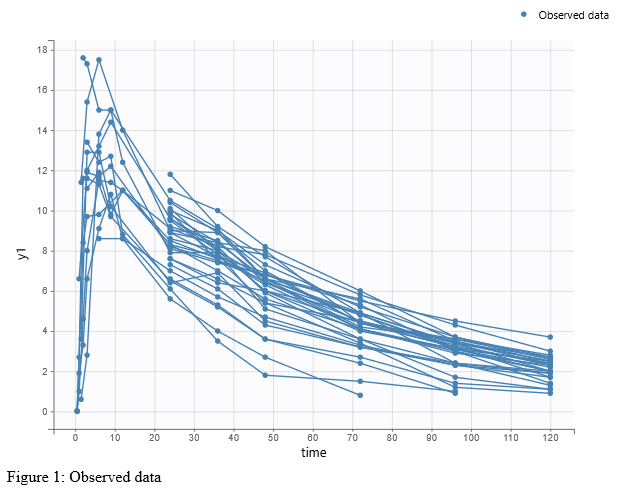

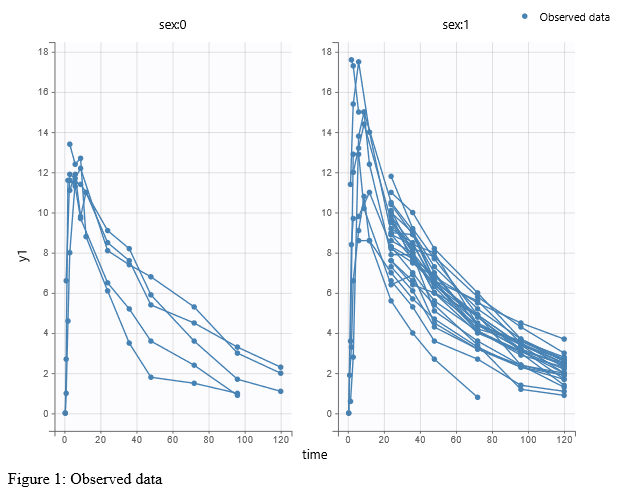

For each OBSERVATION ID, the type of observations must be specified by the user in the interface. Depending on the choice, the data will be displayed in the Observed Data plot in different ways (e.g spaghetti plot for continuous data and Kaplan-Meier plot for event data). The mapping of model outputs and observations from the dataset will also take into account the data type (e.g a model outptu of type “event” can only be mapped to an observation that is also an “event”). Once a model has been selected, the choice of the data types are locked (because they are enforced by the model output type).

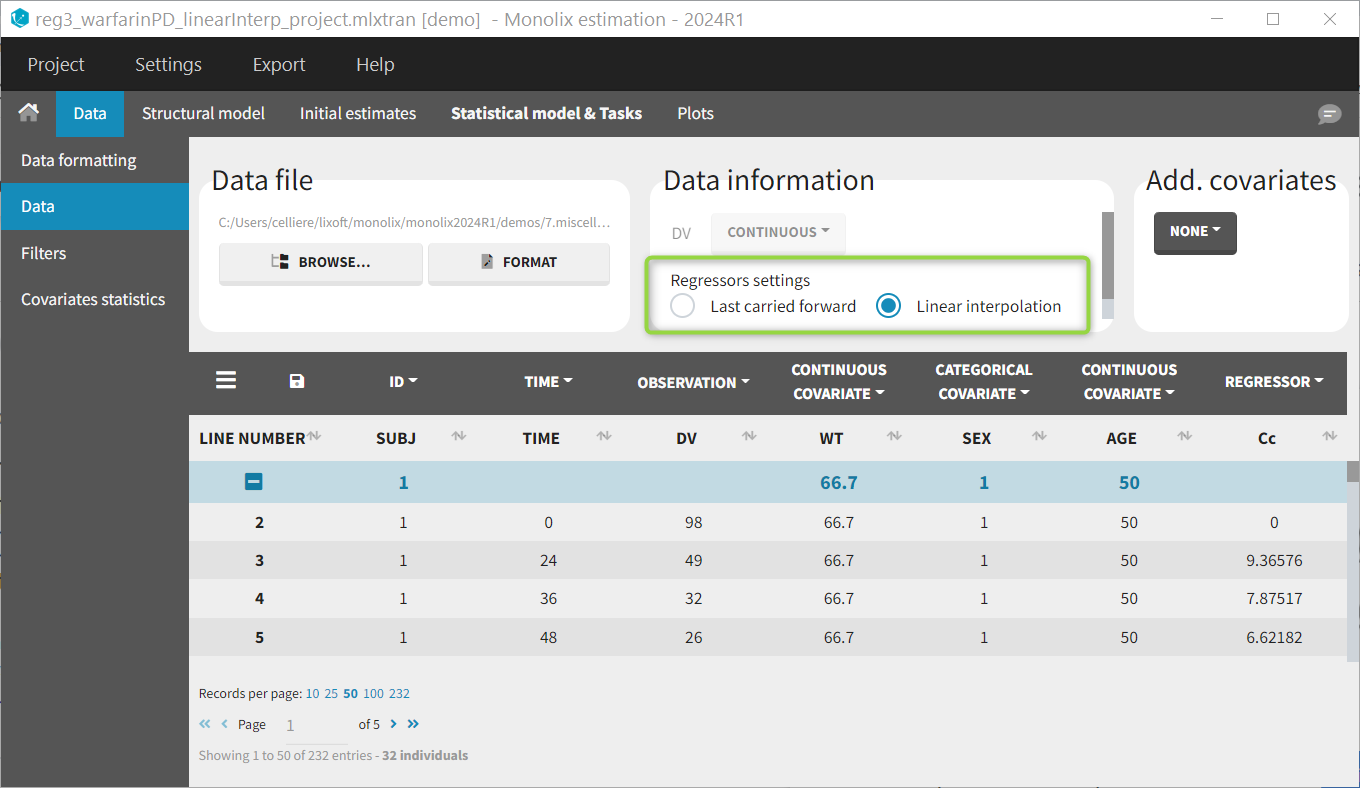

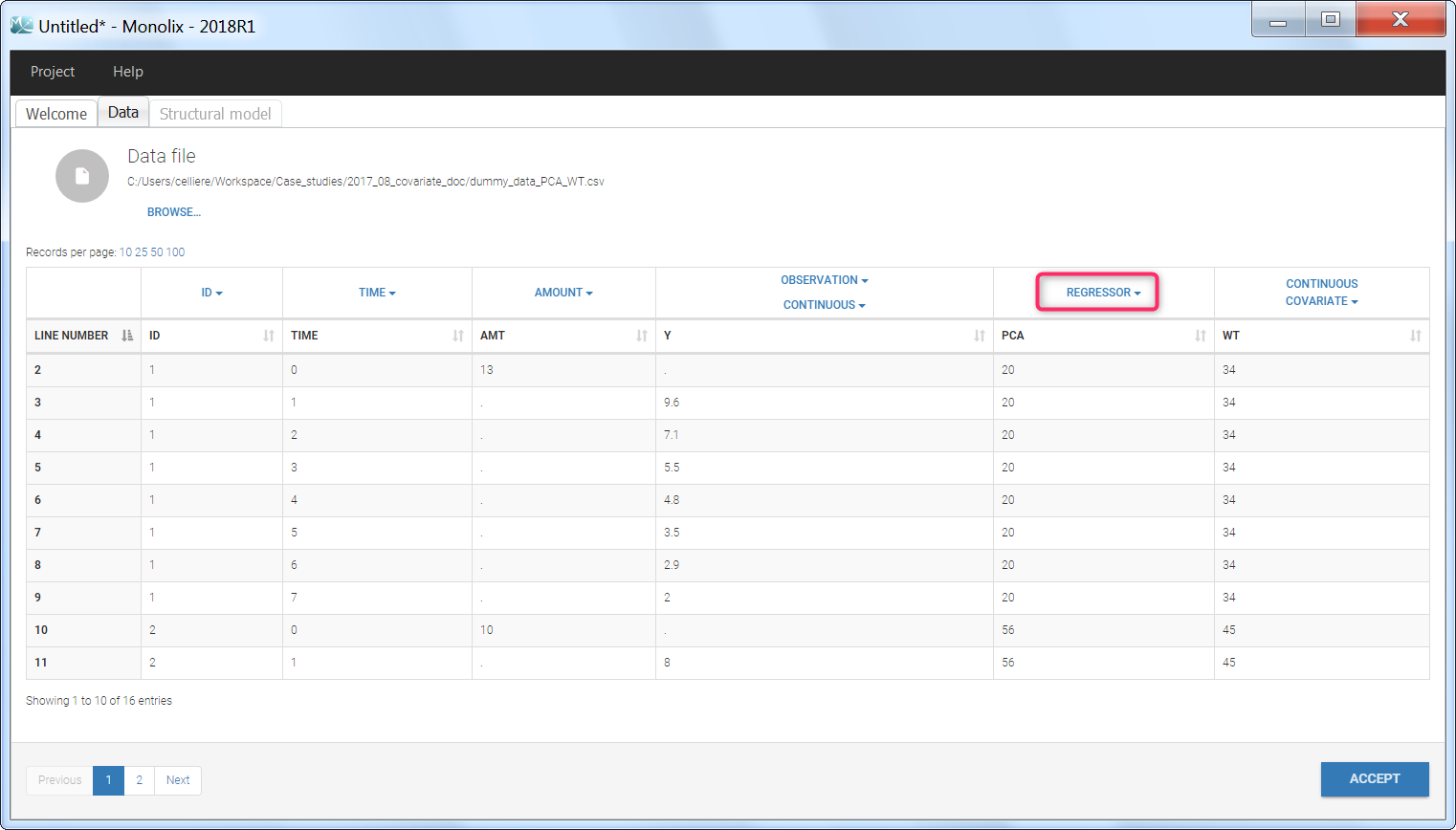

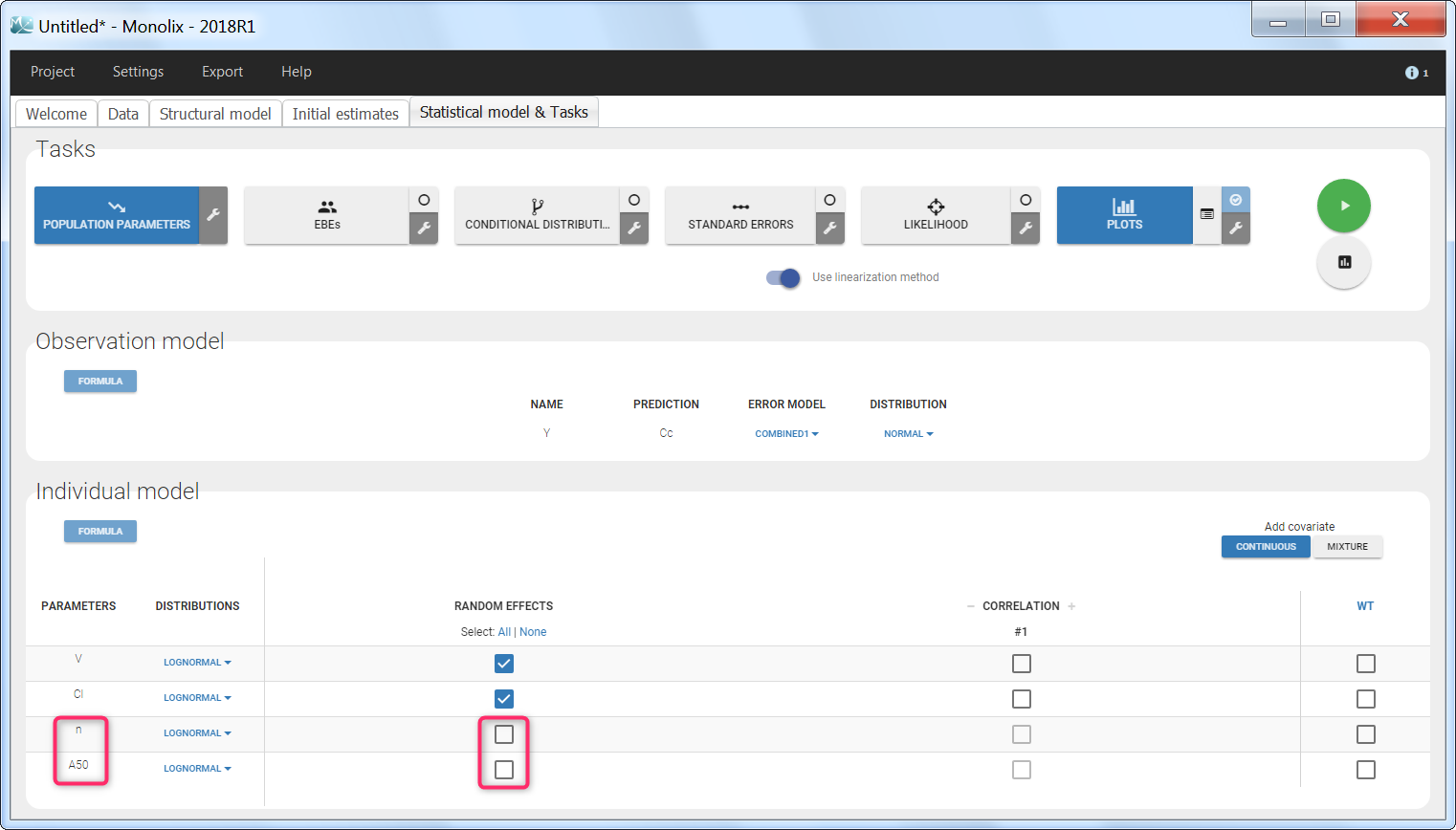

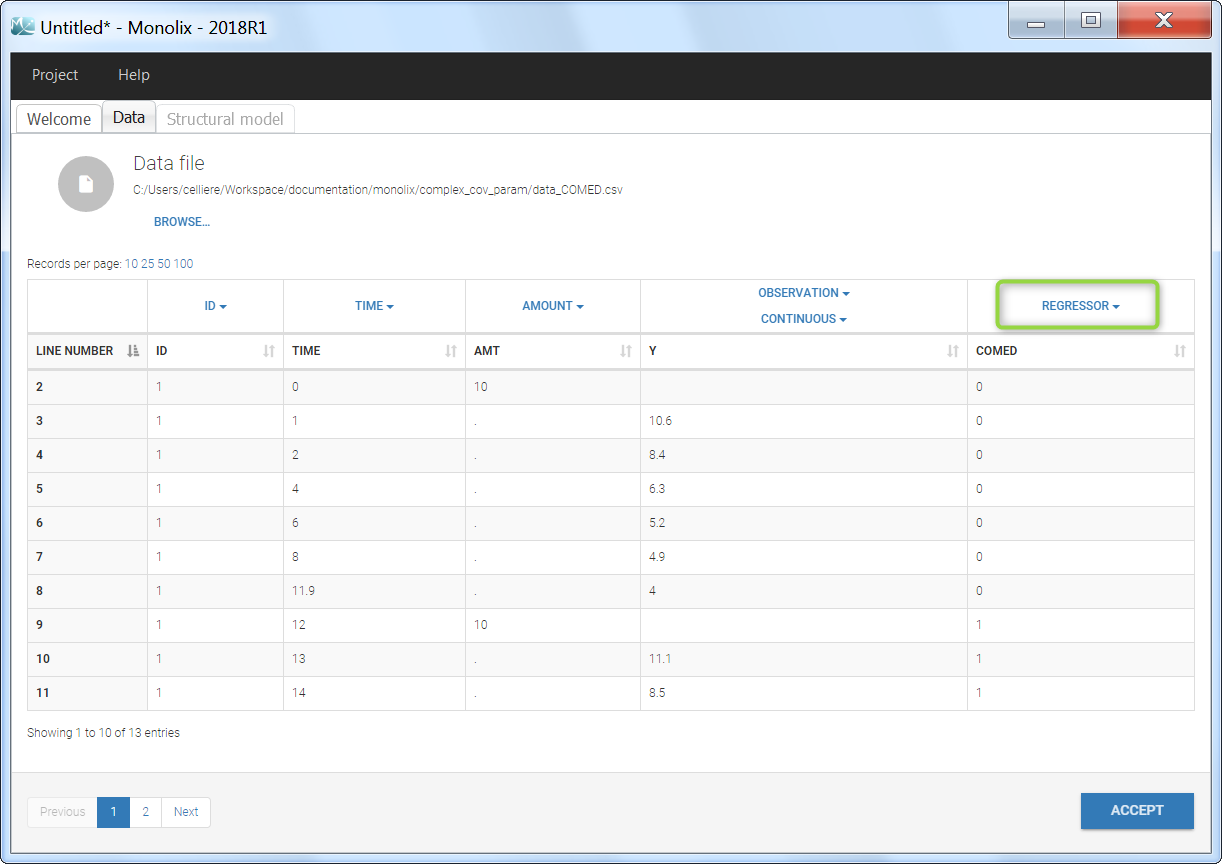

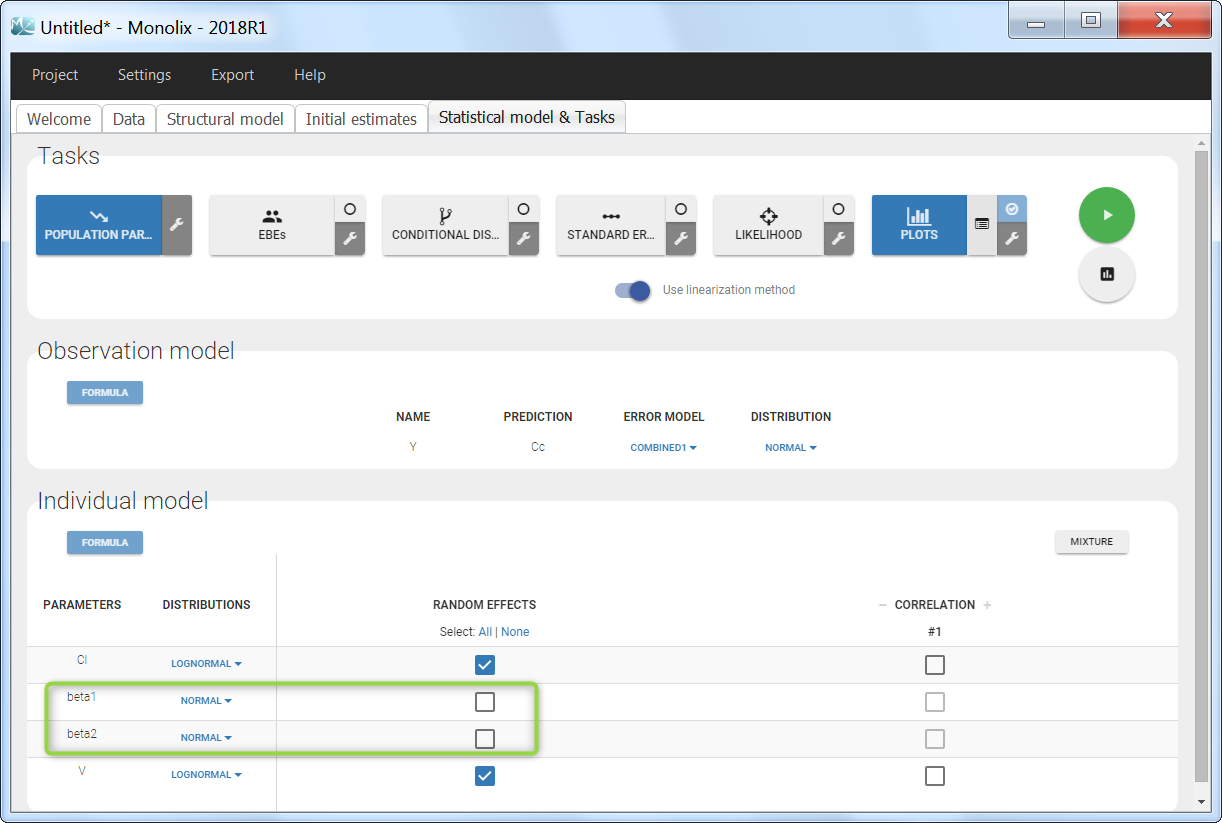

Regressor settings

If columns have been tagged as REGRESSORS, the interpolation method for the regressors can be chosen. In the dataset, regressors are defined only for a finite number of time points. In between those time points, the regressor values can be interpolated in two different ways:

- last carried forward: if we have defined in the dataset two times for each individual with \(reg_A\) at time \(t_A\) and \(reg_B\) at time \(t_B\)

- for \(t\le t_A\), \(reg(t)=reg_A\) [first defined value is used]

- for \(t_A\le t<t_B\), \(reg(t)=reg_A\) [previous value is used]

- for \(t>t_B\), \(reg(t)=reg_B\) [previous value is used]

- linear interpolation: the interpolation is:

- for \(t\le t_A\), \(reg(t)=reg_A\) [first defined value is used]

- for \(t_A\le t<t_B\), \(reg(t)=reg_A+(t-t_A)\frac{(reg_B-reg_A)}{(t_B-t_A)}\) [linear interpolation is used]

- for \(t>t_B\), \(reg(t)=reg_B\) [previous value is used]

The interpolation is used to obtain the regressor value at times not defined in the dataset. This is necessary to integrate ODE-based models (which are using an internal adaptative time step), or obtain prediction on a fine grid for the plots (e.g in the Individuals fits) for instance.

When some dataset lines have a missing regressor value (dot “.”), the same interpolation method is used.

Labeling (column tagging)

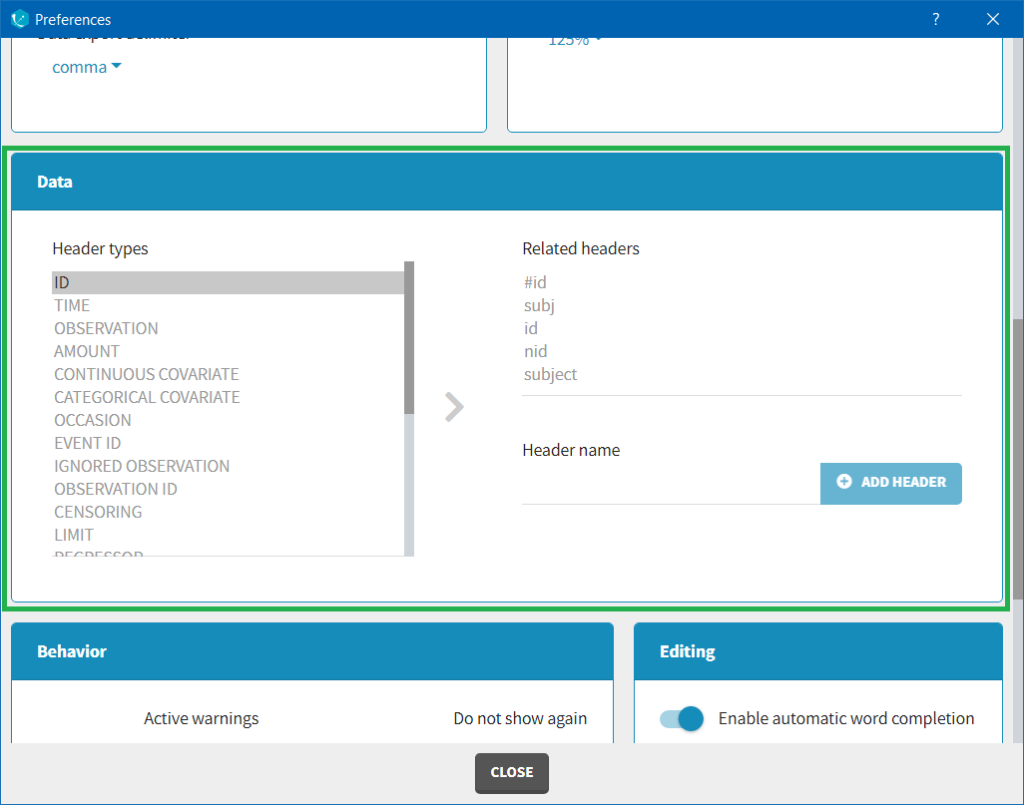

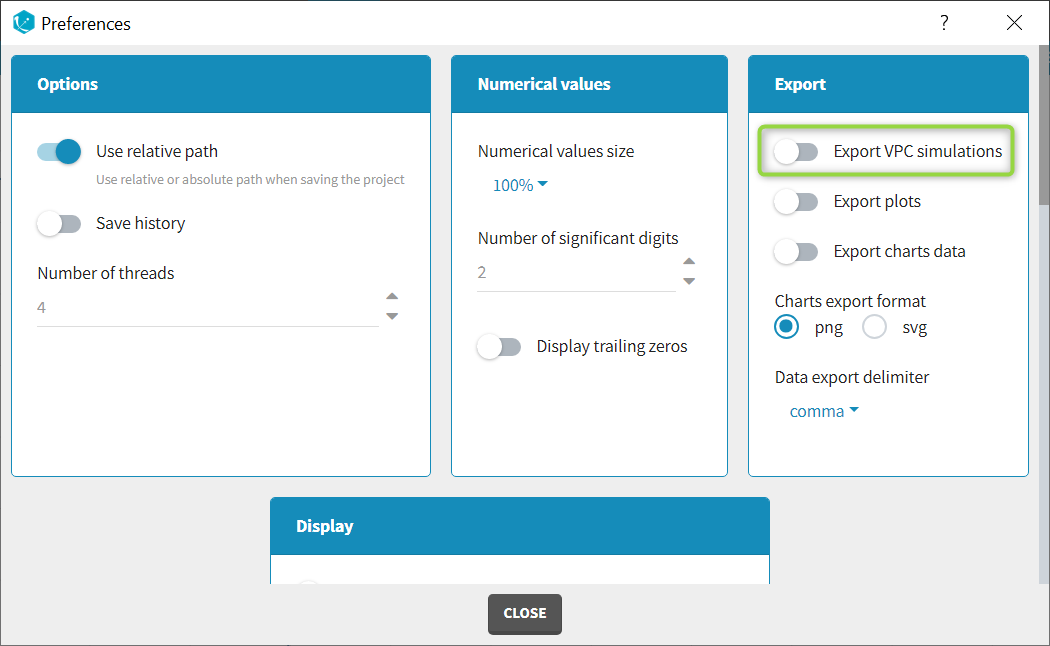

The column type suggested automatically by Monolix based on the headers in the data can be customized in the preferences. By clicking on Settings>Preferences, the following windows pops up.

In the DATA frame, you can add or remove preferences for each column.

To remove a preference, double-click on the preference you would like to remove. A confirmation window will be proposed.

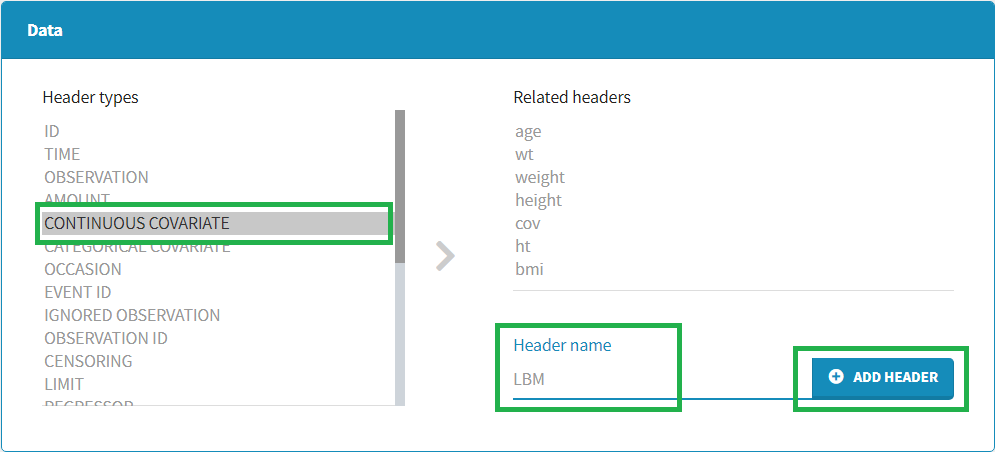

To add a preference, click on the header type you consider, add a name in the header name and click on “ADD HEADER” as on the following figure.

Notice that all the preferences are shared between Monolix, Datxplore, and PKanalix.

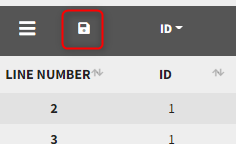

Starting from the version 2024, it is also possible to update the preferences with the columns tagged in the opened project, by clicking on the icon in the top left corner of the table:

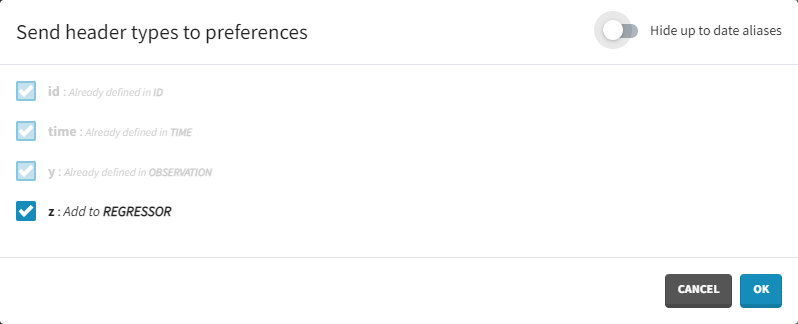

Clicking on the icon will open a modal with the option to choose which of the tagged headers a user wants to add to preferences:

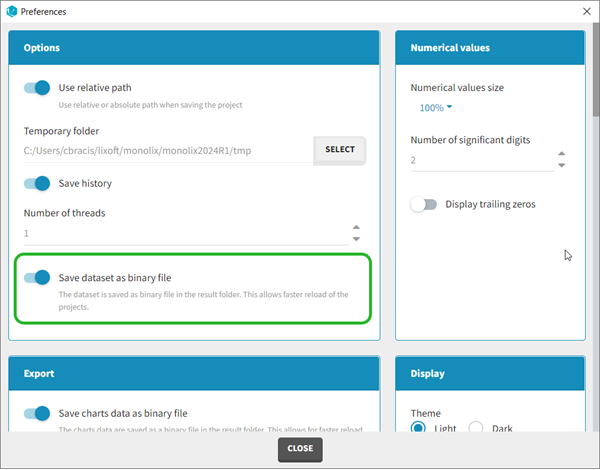

Dataset load times

Starting with the 2024 version, it is possible to improve the project load times, especially for projects with large datasets, but saving the data as a binary file. This option is available in Settings>Preferences and will save a copy of the data file in binary format in the results folder. When reloading a project, the dataset will be read from the binary file, which will be faster. If the original dataset file has been modified (compared to the binary), a warning message will appear, the binary dataset will not be used and the original dataset fiel will be loaded instead.

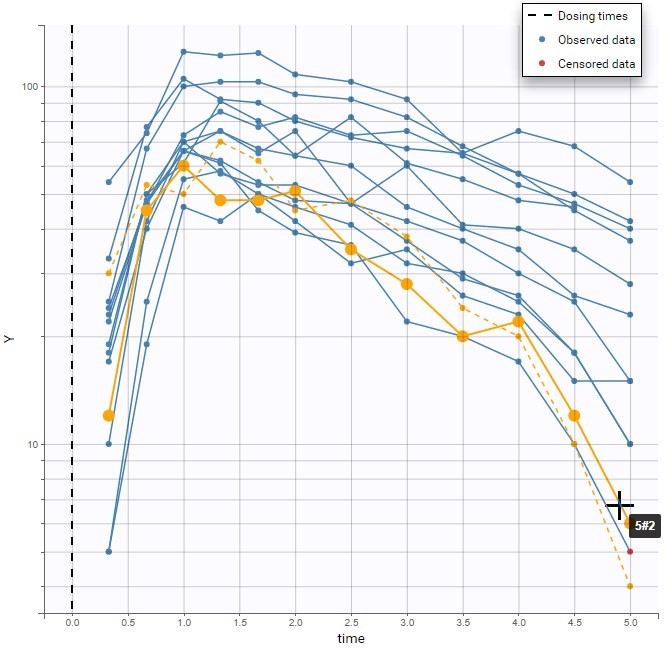

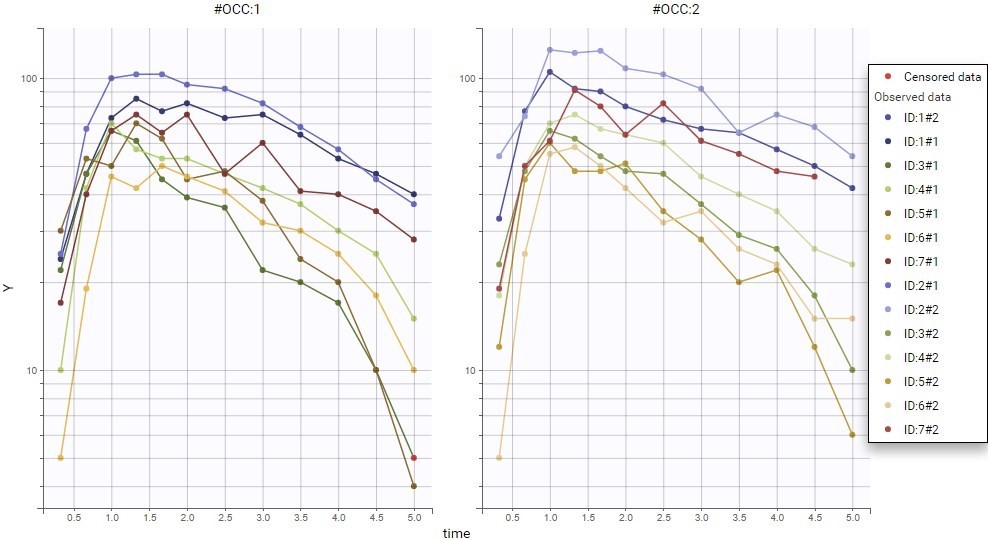

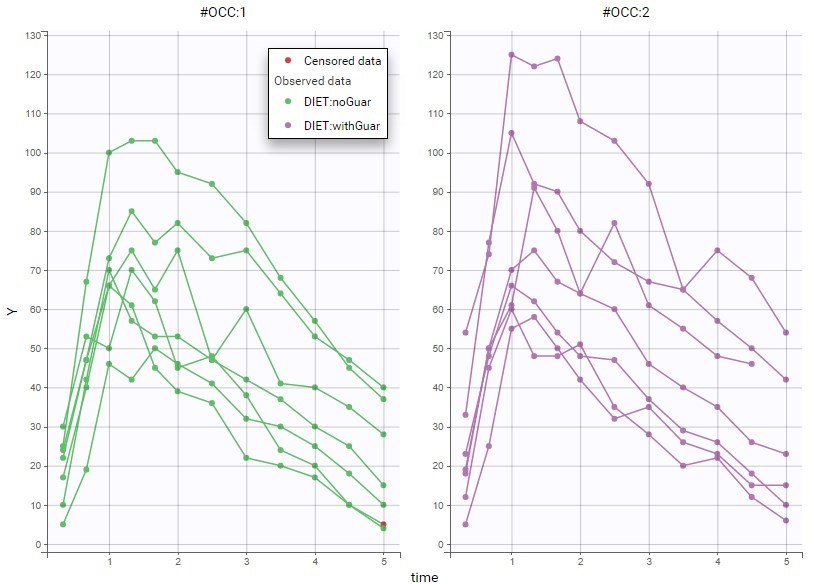

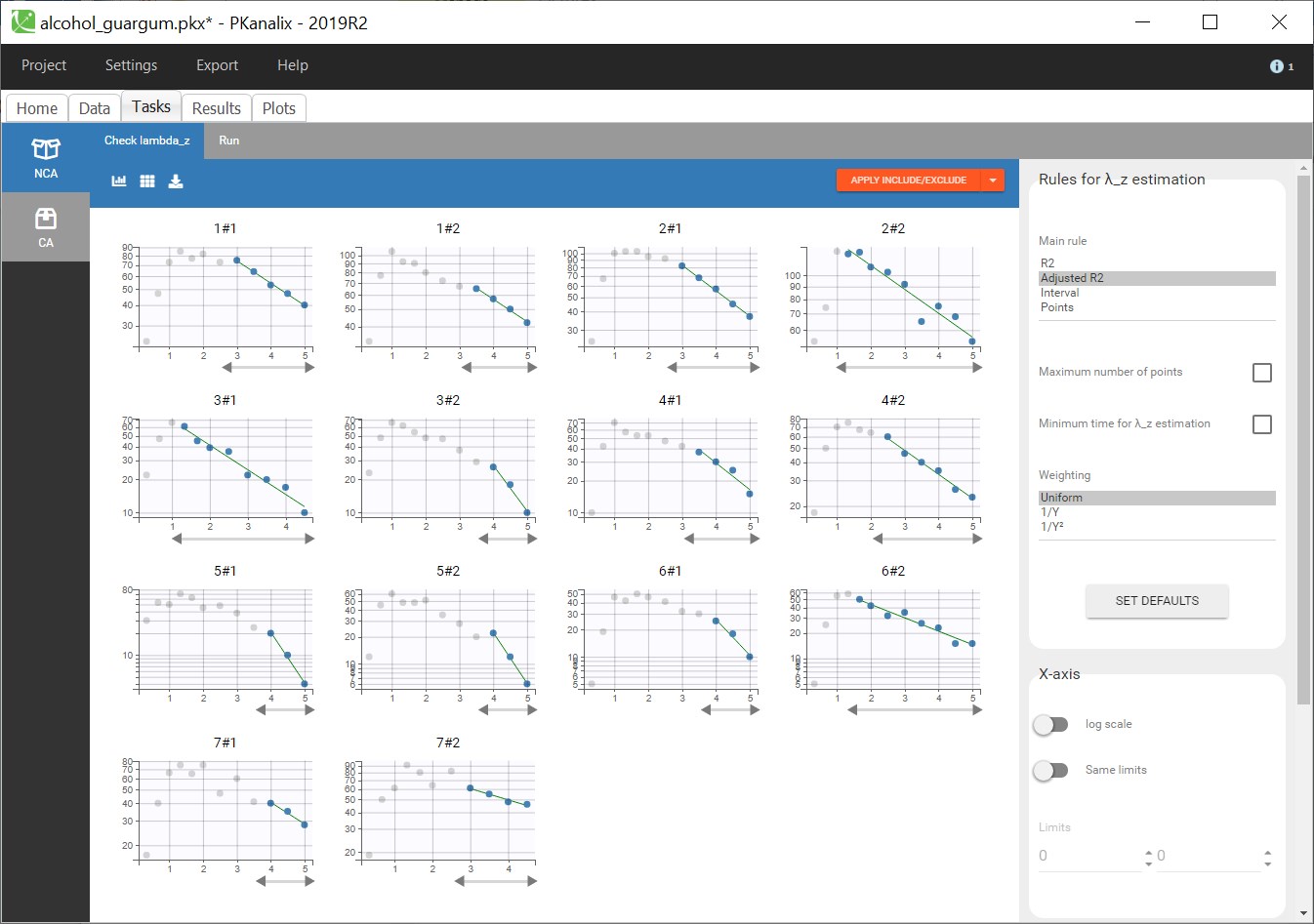

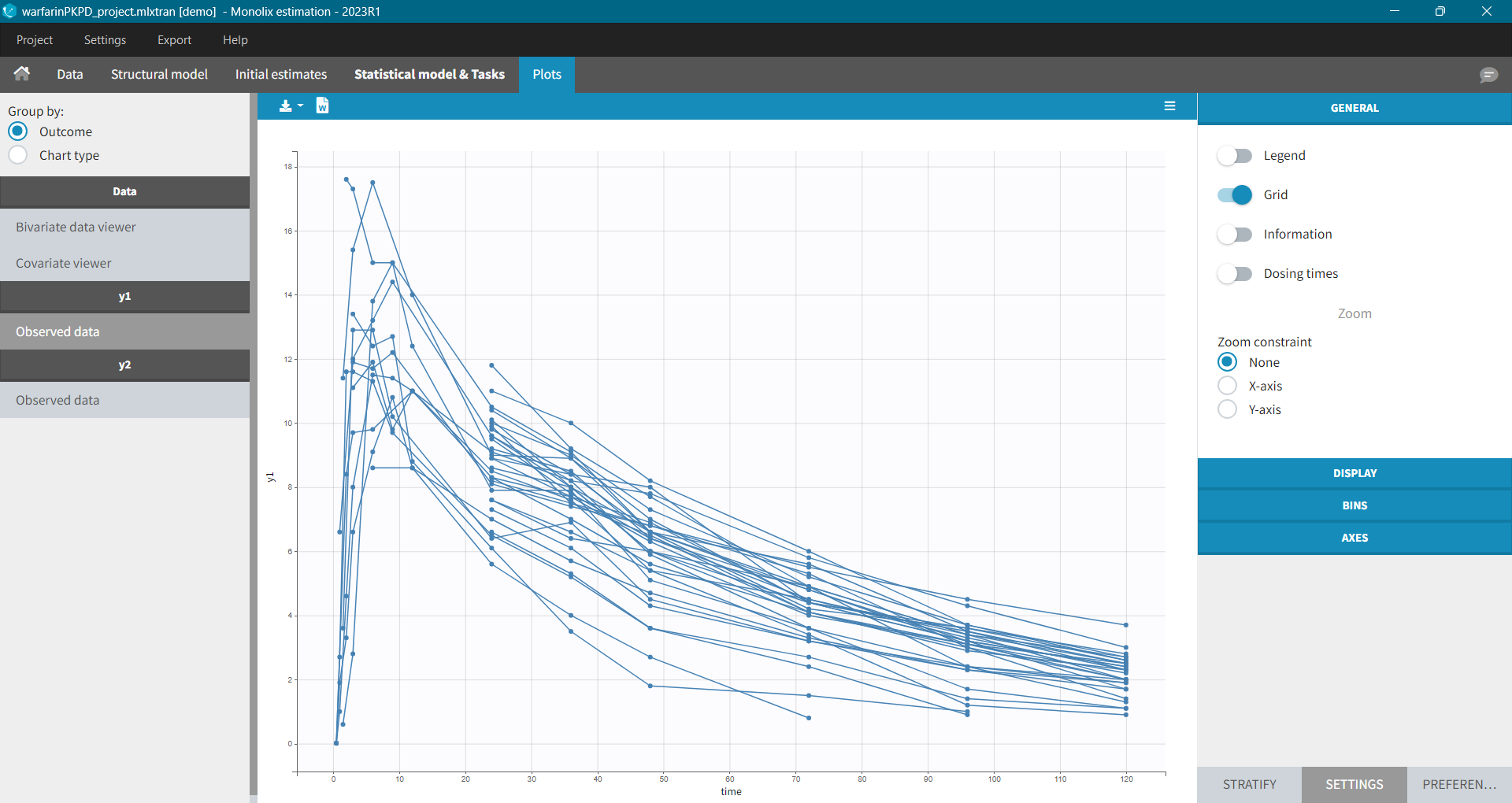

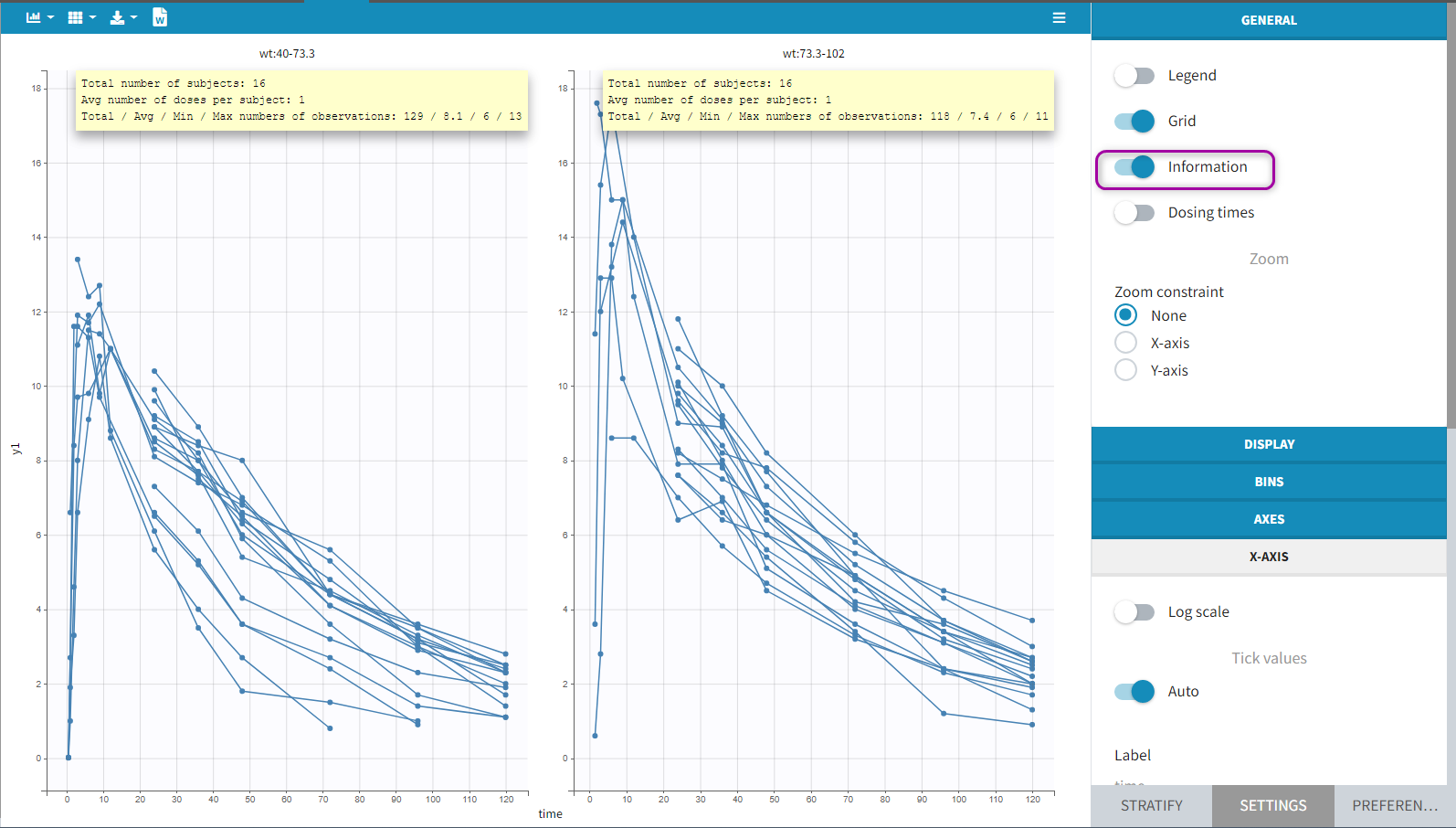

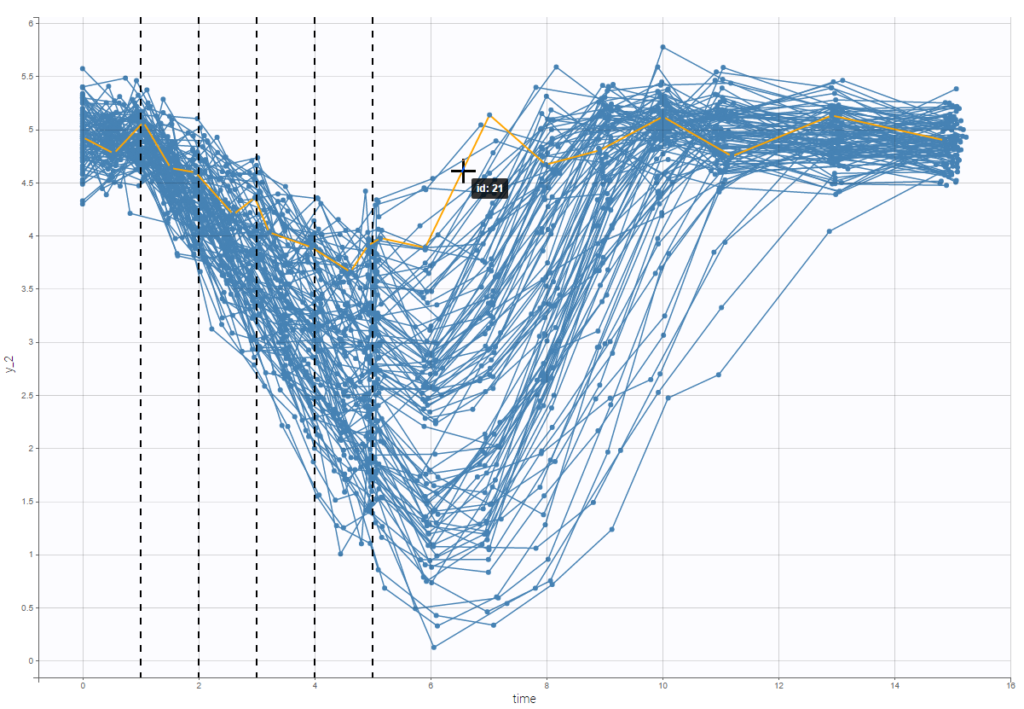

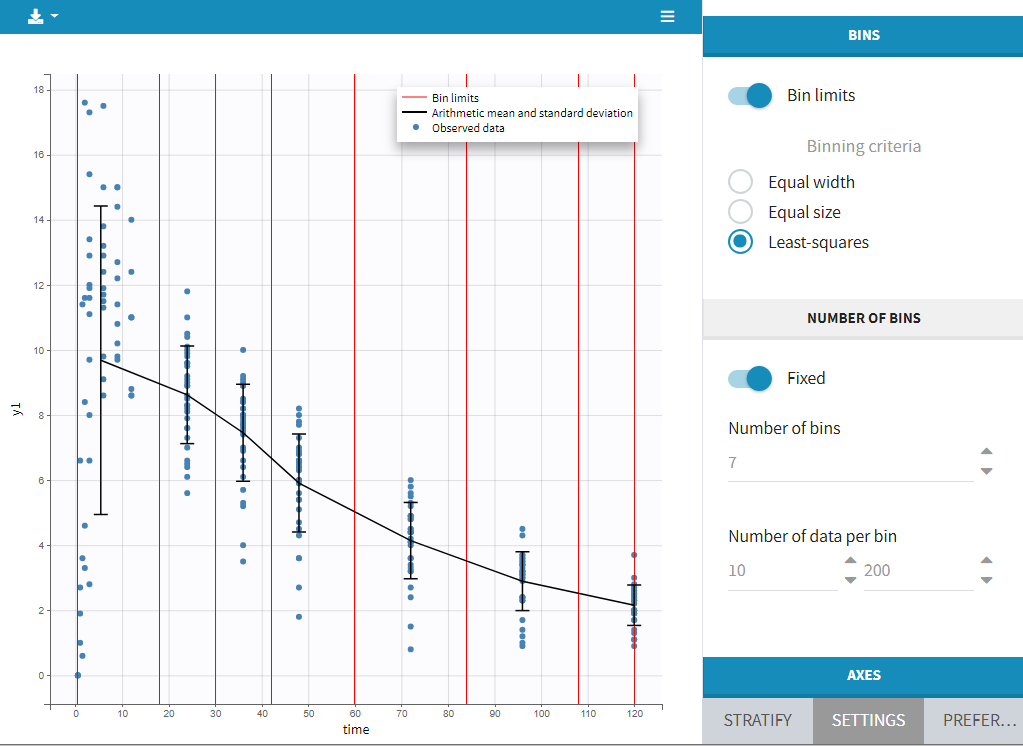

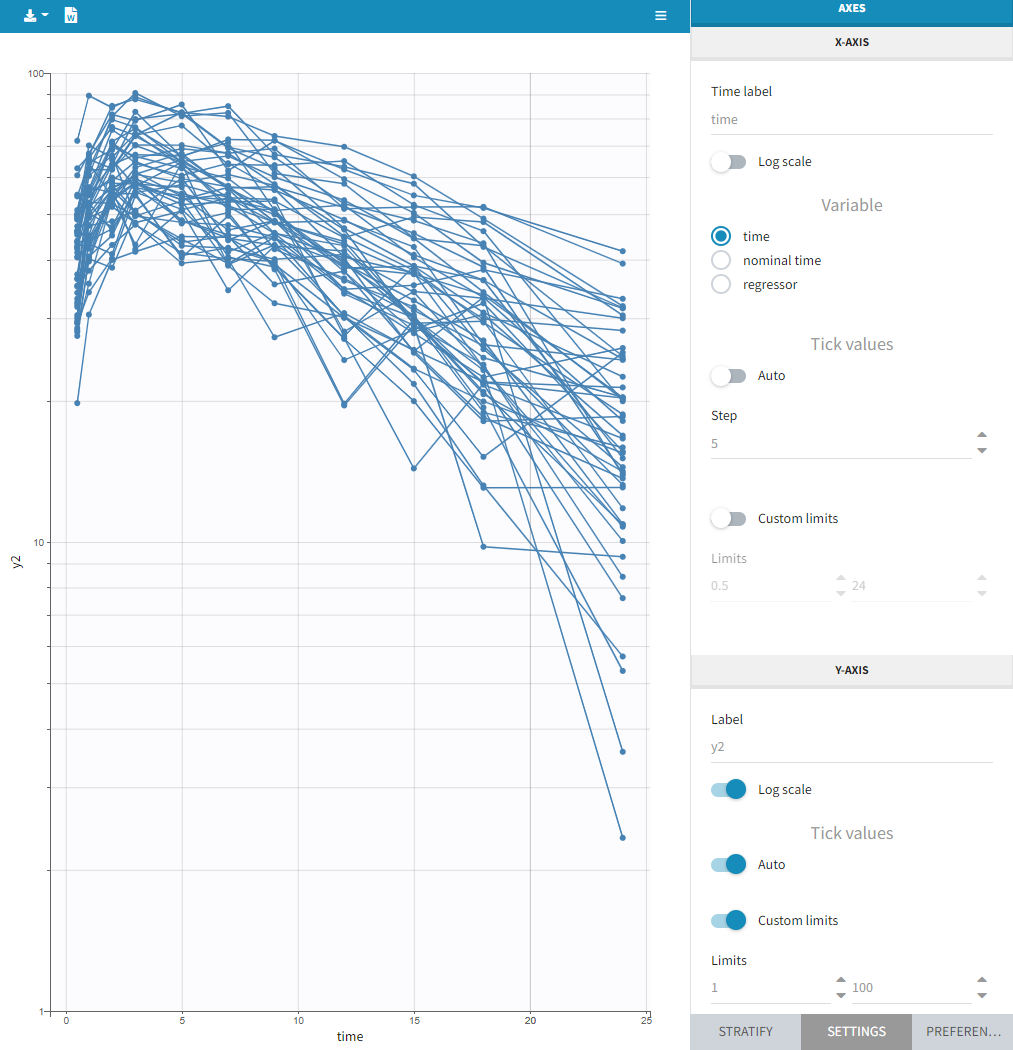

Resulting plots and tables to explore the data

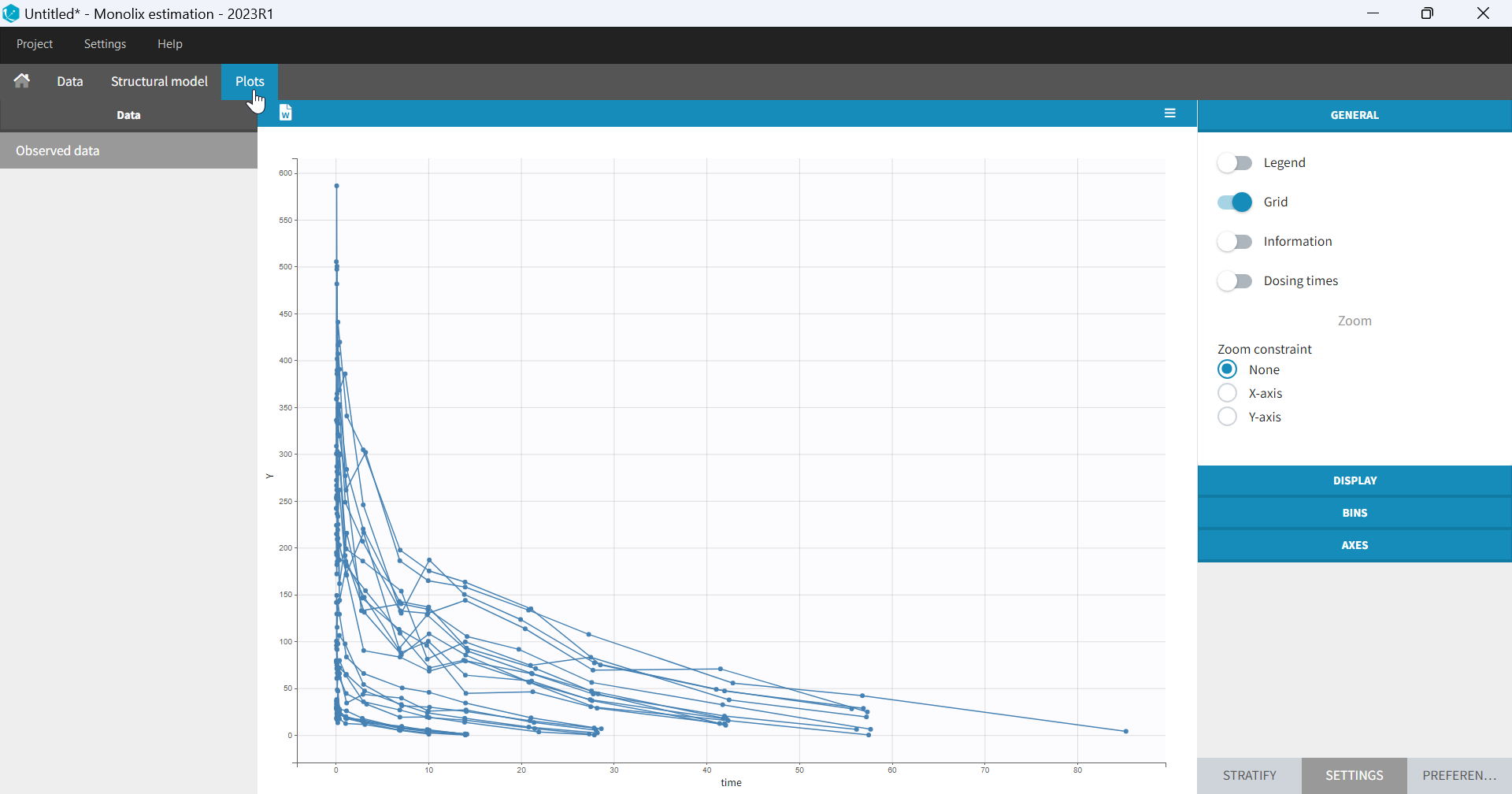

Once the dataset is accepted:

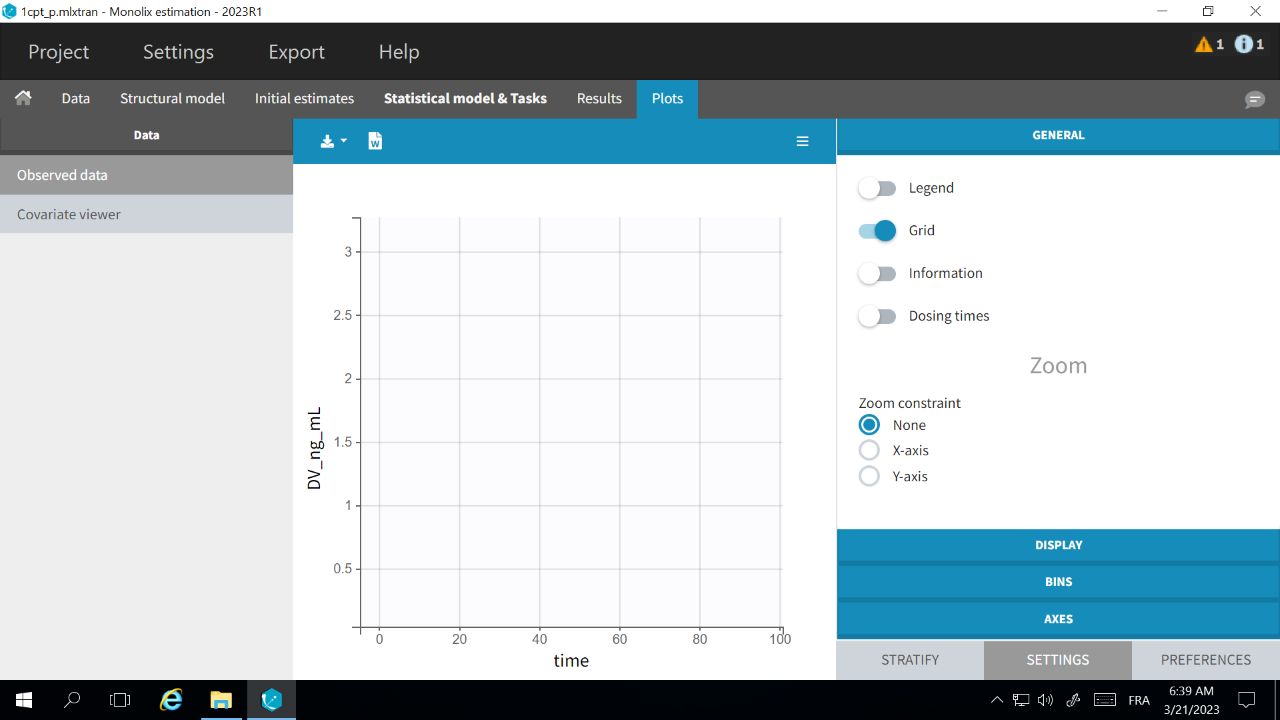

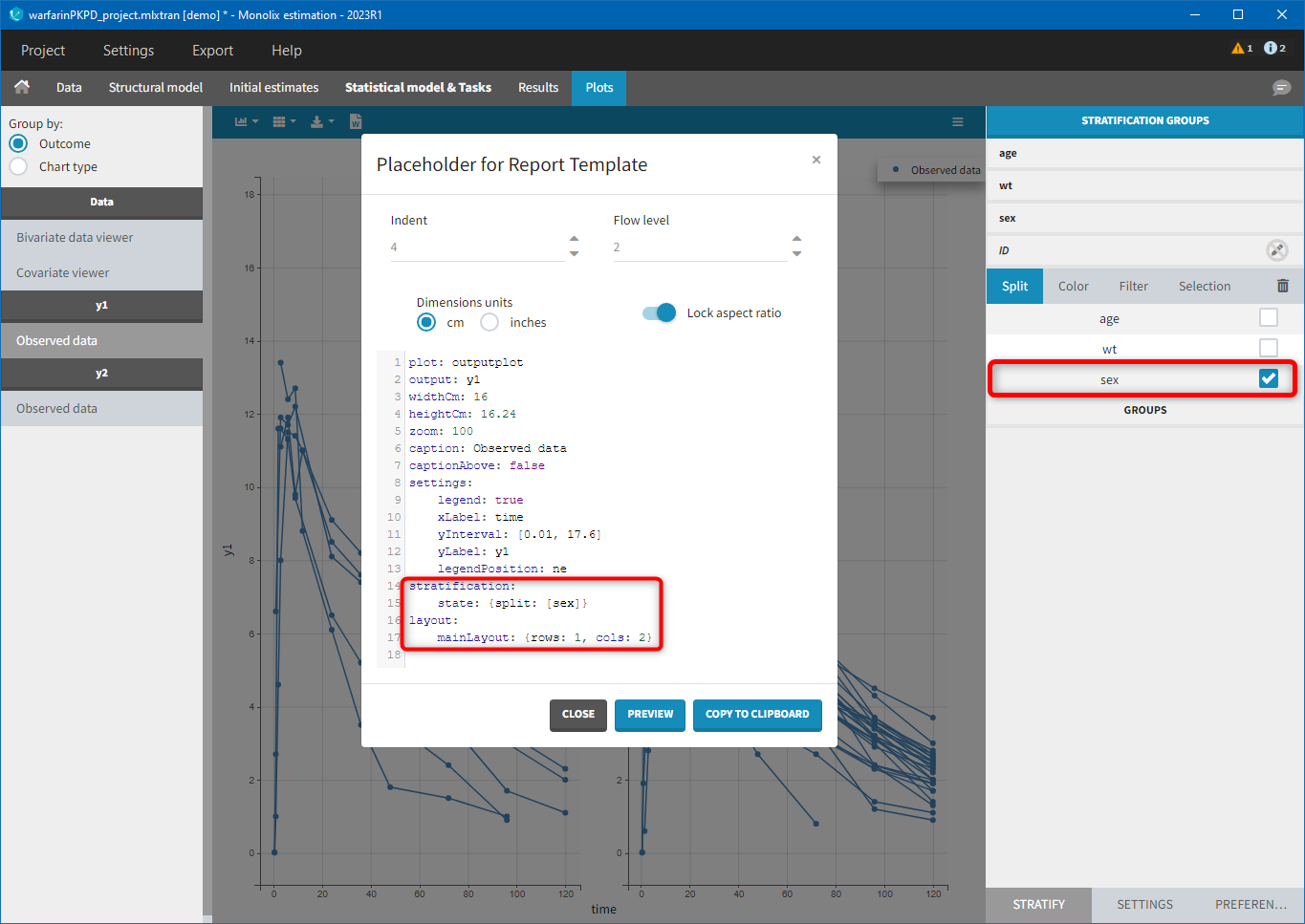

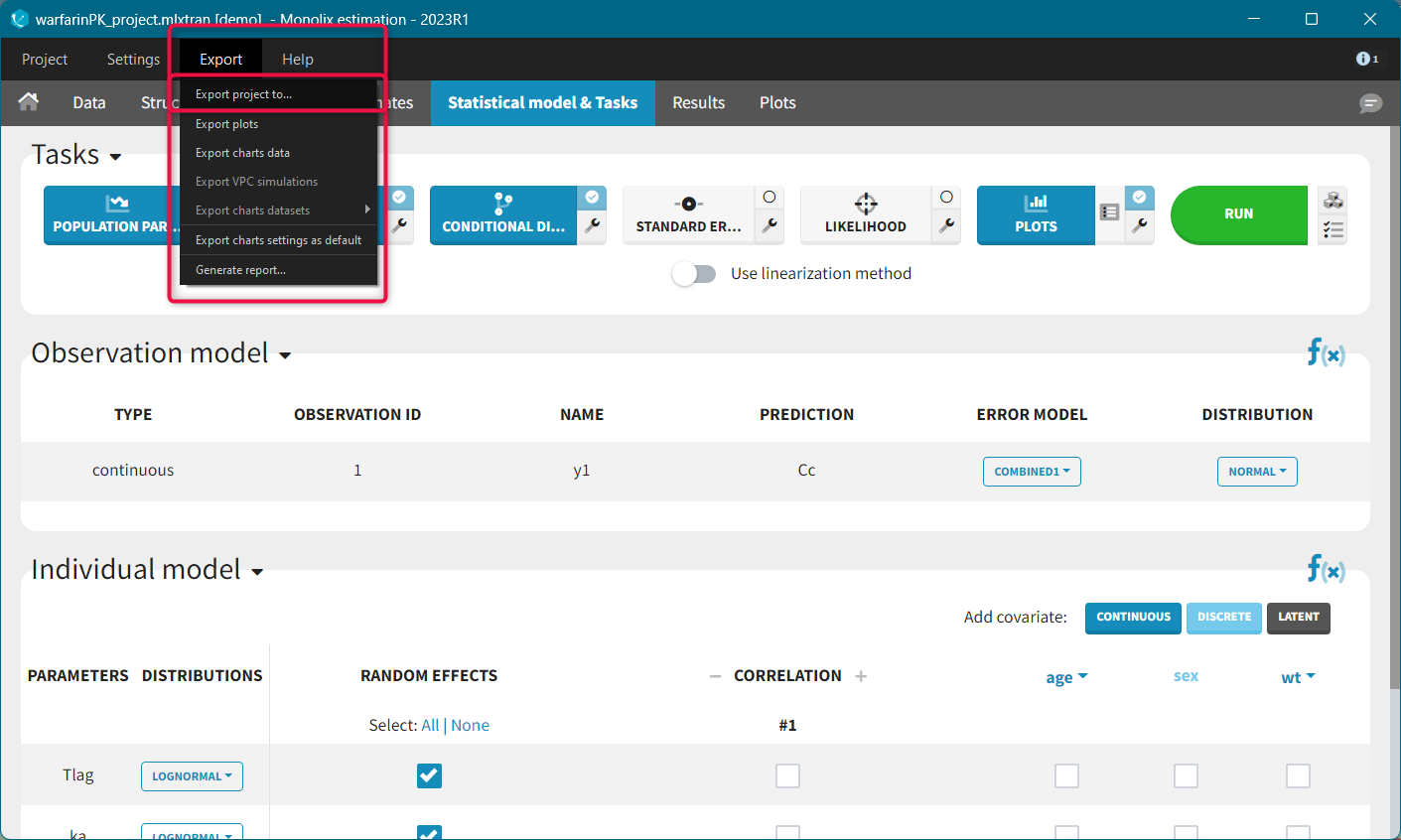

- Plots are automatically generated based on the interpreted dataset to help you proceed with a first data exploration before running any task.

- The interpreted dataset appears in Data tab, which incorporates all changes after formatting and filtering.

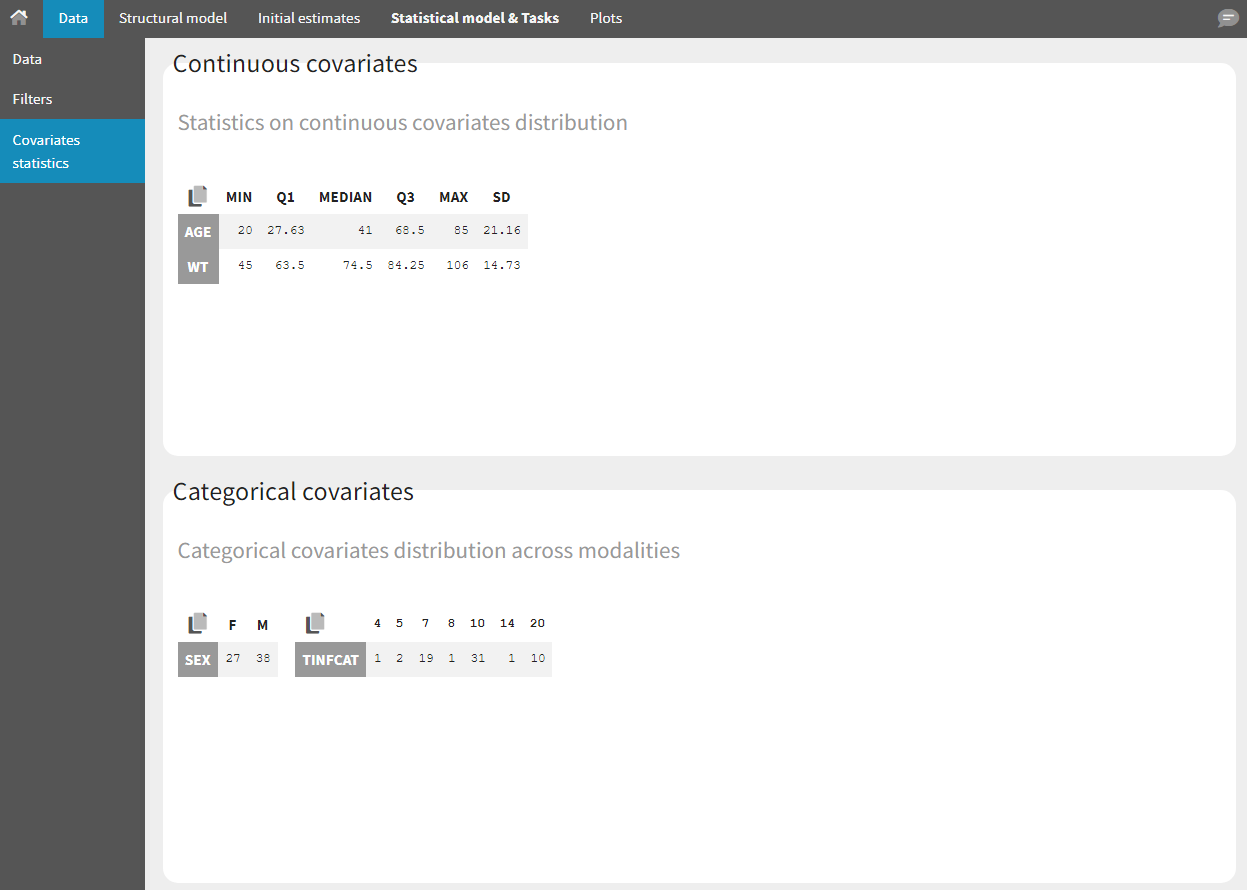

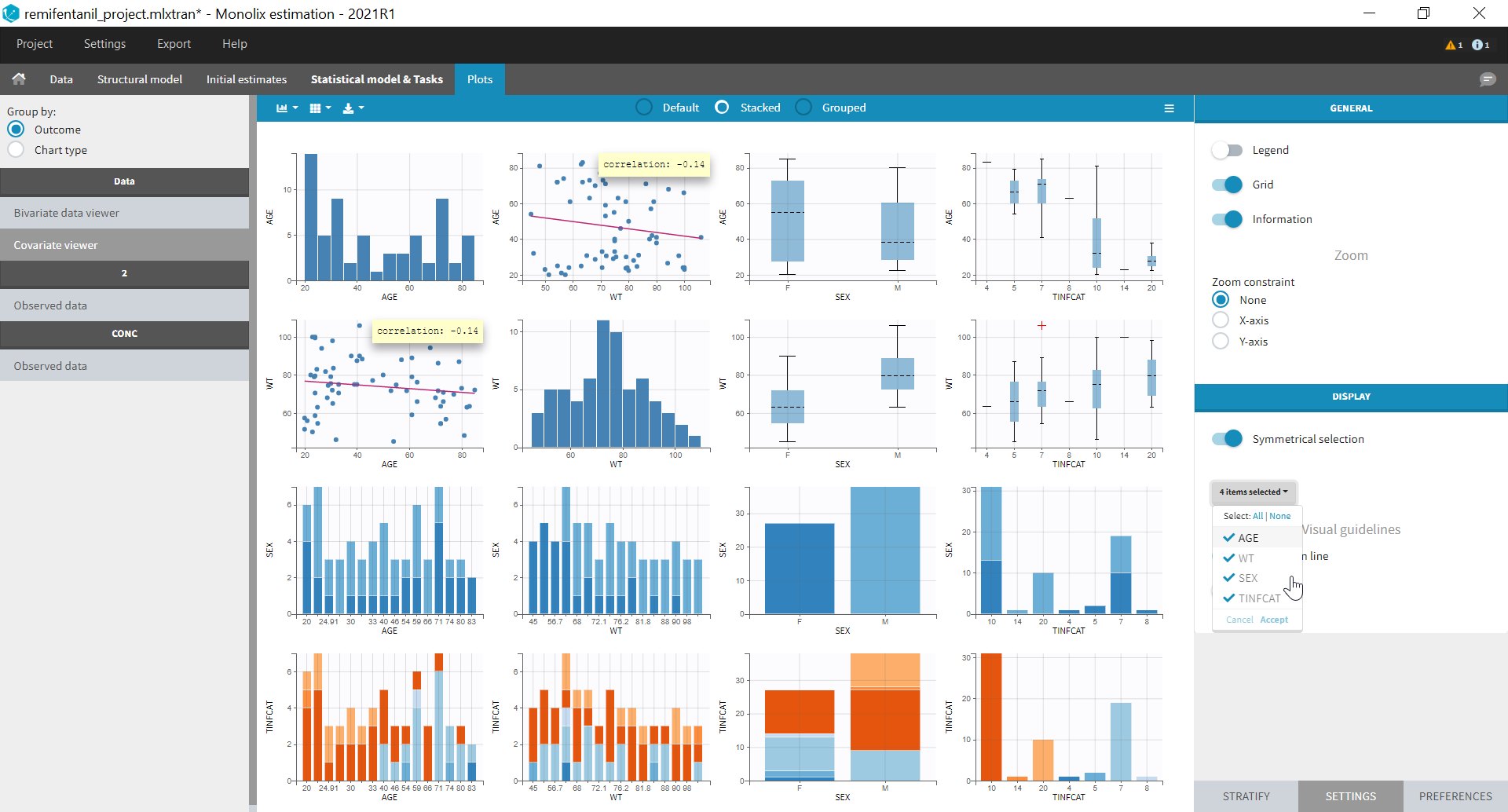

- Covariate Statistics appear in a section of the data tab.

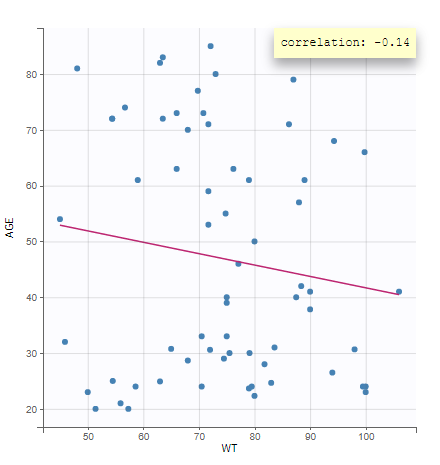

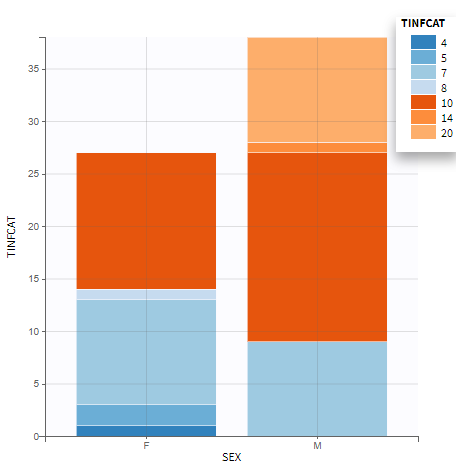

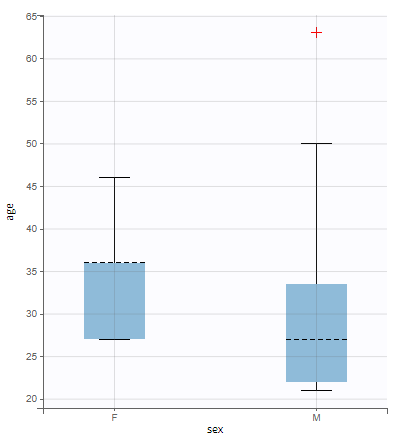

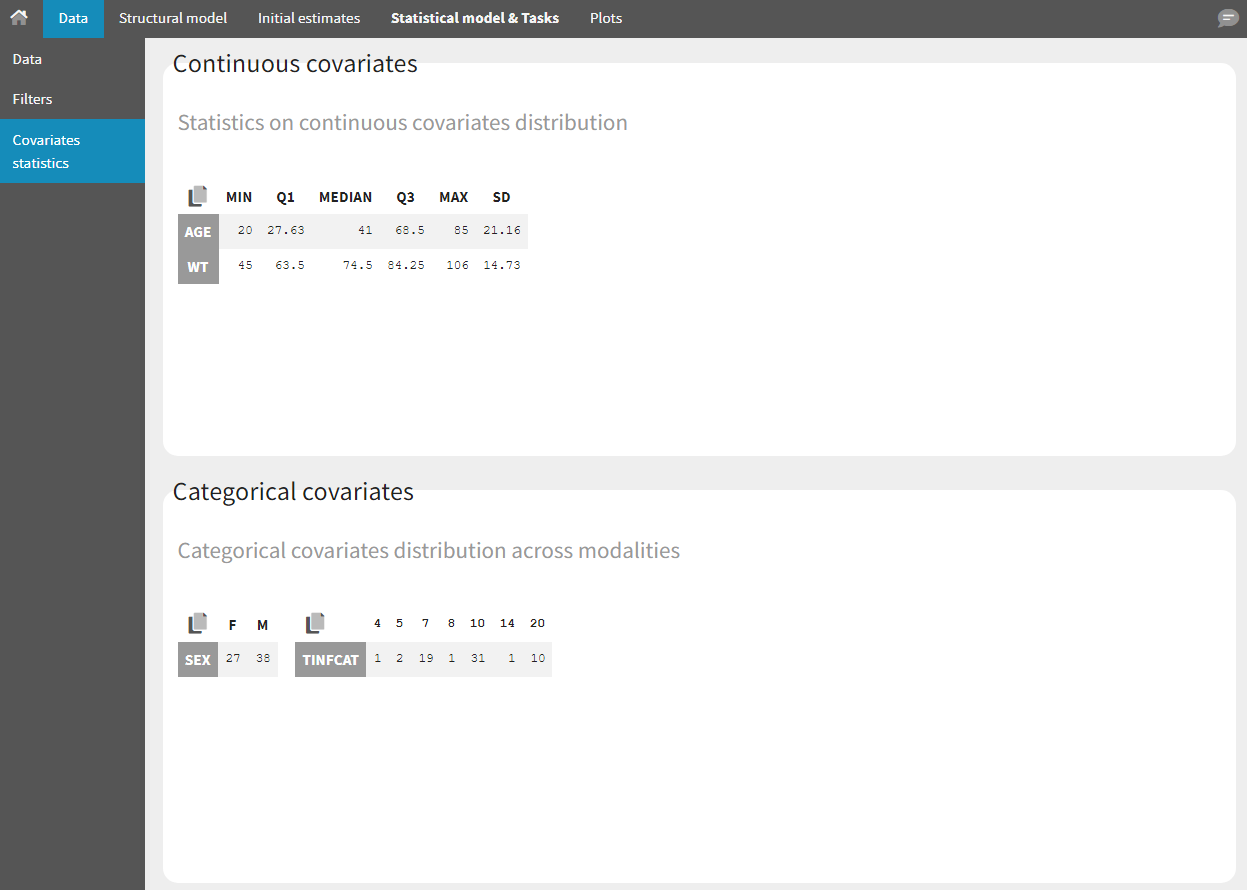

All the covariates (if any) are displayed and a summary of the statistics is proposed. For continuous covariates, minimum, median and maximum values are proposed along with the first and third quartile, and the standard deviation. For categorical covariates, all the modalities are displayed along with the number of each. Note the “Copy table” button that allows to copy the table in Word and Excel. The format and the display of the table will be preserved.

Importing a project from Datxplore or PKanalix

It is possible to import a project from Datxplore or PKanalix. For that, go to Project>New project for Datxplore/PKanalix (as in the green box of the following figure). In that case, a new project will be created and all the DATA frame will already be filled by the information from the Datxplore or PKanalix project.

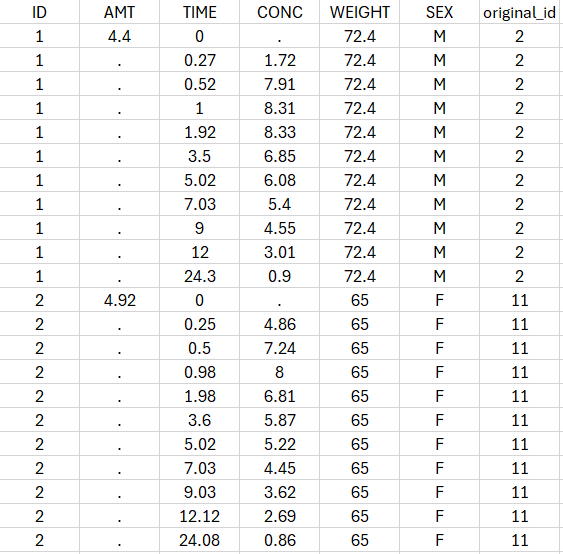

2.2.Data Format

- Each line corresponds to one individual and one time point.

- Each line can include a single measurement (also called observation), or a dose amount (or both a measurement and a dose amount).

- Dosing information should be indicated for each individual in a specific column, even if it is the same treatment for all individuals.

- Headers are free but there can be only one header line.

- Different types of information (dose, observation, covariate, etc) are recorded in different columns, which must be tagged with a column type (see below).

Notice that Monolix often provides an initial guess of the type of the column depending on the name.

Notice that Monolix often provides an initial guess of the type of the column depending on the name.

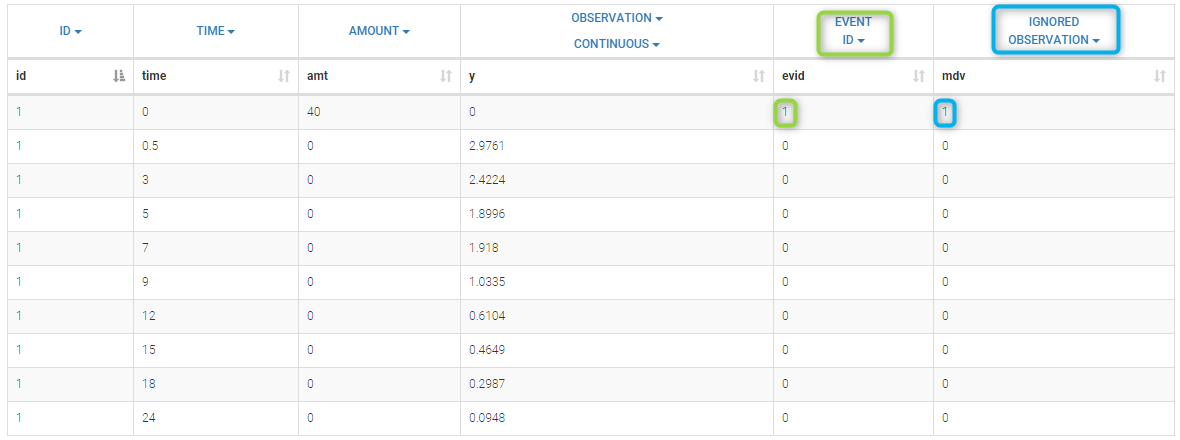

Description of column-types

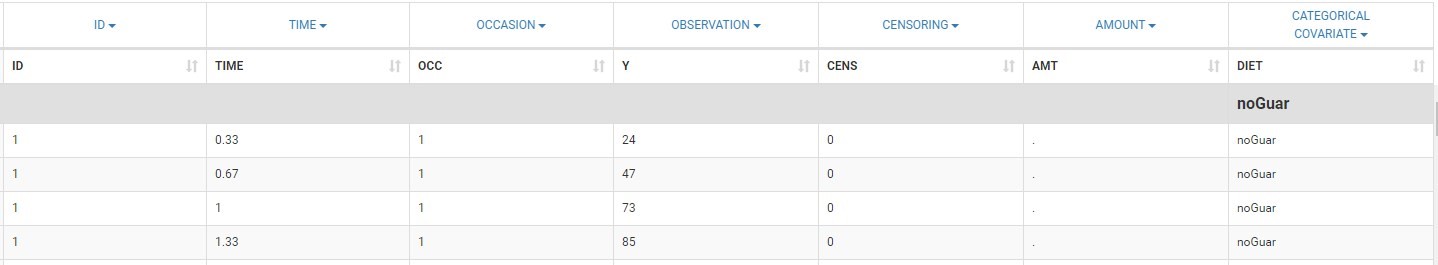

The first line of the data set must be a header line, defining the names of the columns. The columns names are completely free. In the MonolixSuite applications, when defining the data, the user will be asked to assign each column to a column-type (see here for an example of this step). The column type will indicate to the application how to interpret the information in that column. The available column types are given below. Column-types used for all types of lines:- ID (mandatory): identifier of the individual

- OCCASION (formerly OCC): identifier (index) of the occasion

- TIME: time of the dose or observation record

- DATE/DAT1/DAT2/DAT3: date of the dose or observation record, to be used in combination with the TIME column

- EVENT ID (formerly EVID): identifier to indicate if the line is a dose-line or a response-line

- IGNORED OBSERVATION (formerly MDV): identifier to ignore the OBSERVATION information of that line

- IGNORED LINE (from 2019 version): identifier to ignore all the information of that line

- CONTINUOUS COVARIATE (formerly COV): continuous covariates (which can take values on a continuous scale)

- CATEGORICAL COVARIATE (formerly CAT): categorical covariate (which can only take a finite number of values)

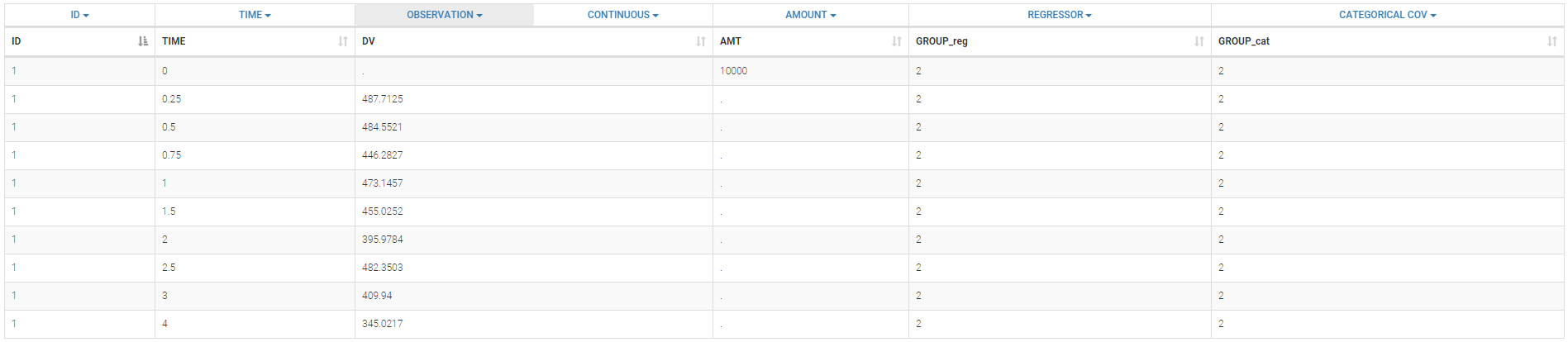

- REGRESSOR (formerly X): defines a regression variable, i.e a variable that can be used in the structural model (used e.g for time-varying covariates)

- IGNORE: ignores the information of that column for all lines

- OBSERVATION (mandatory, formerly Y): records the measurement/observation for continuous, count, categorical or time-to-event data

- OBSERVATION ID (formerly YTYPE): identifier for the observation type (to distinguish different types of observations, e.g PK and PD)

- CENSORING (formerly CENS): marks censored data, below the lower limit or above the upper limit of quantification

- LIMIT: upper or lower boundary for the censoring interval in case of CENSORING column

- AMOUNT (formerly AMT): dose amount

- ADMINISTRATION ID (formerly ADM): identifier for the type of dose (given via different routes for instance)

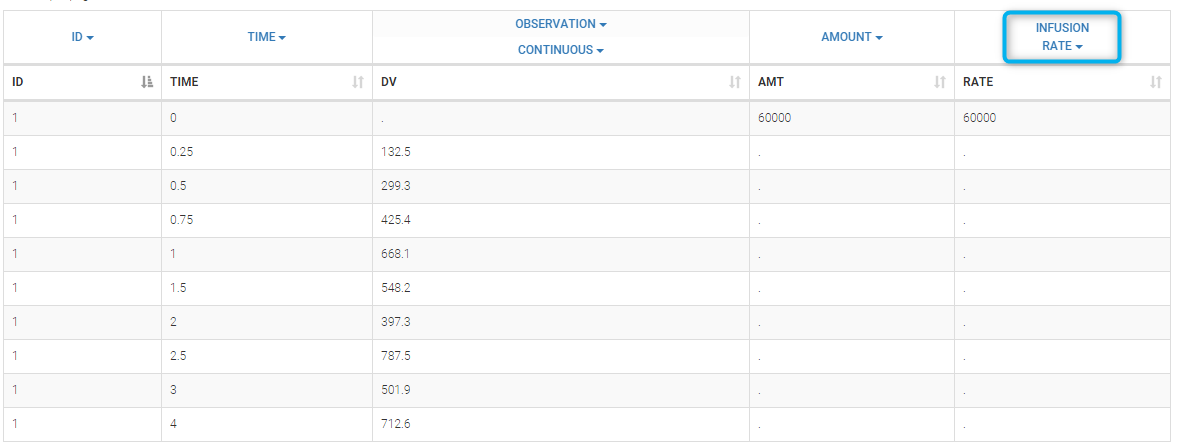

- INFUSION RATE (formerly RATE): rate of the dose administration (used in particular for infusions)

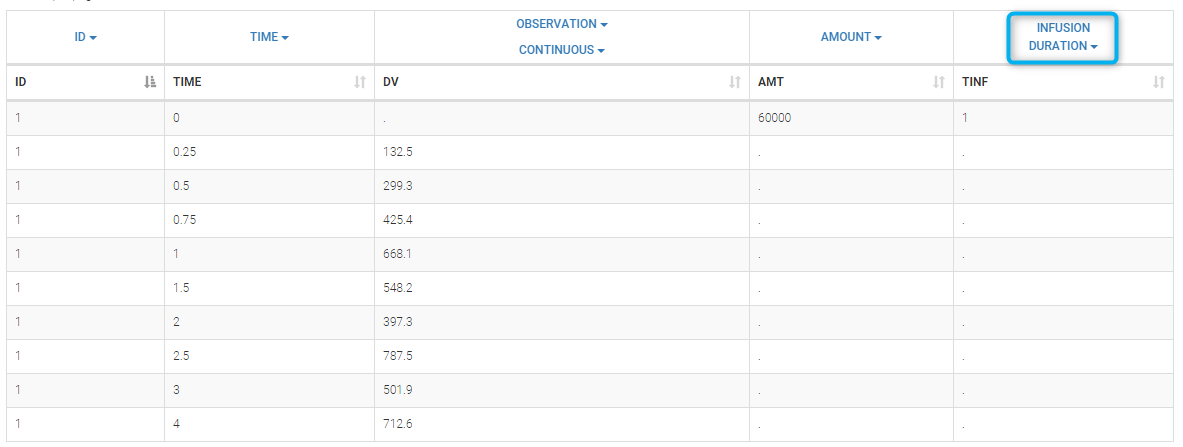

- INFUSION DURATION (formerly TINF): duration of the dose administration (used in particular for infusions)

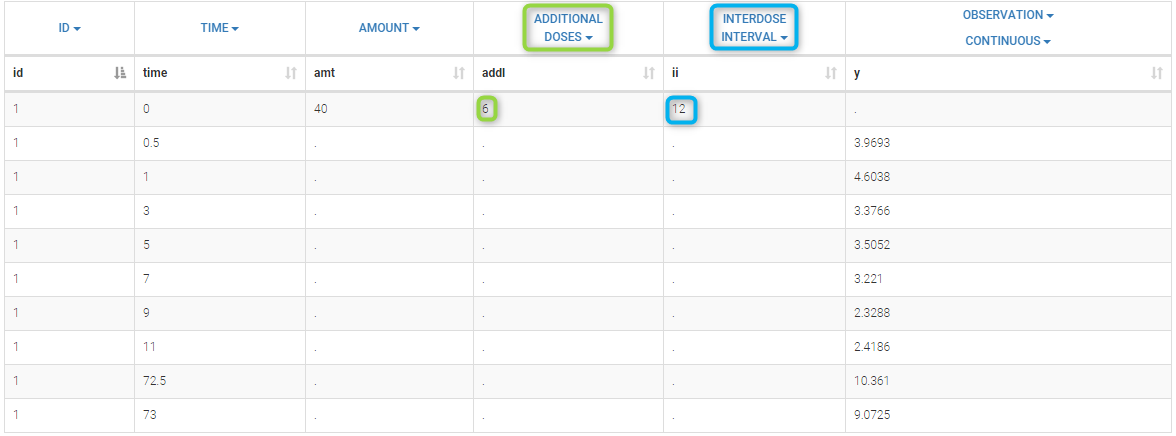

- ADDITIONAL DOSES (formerly ADDL): number of doses to add in addition to the defined dose, at intervals INTERDOSE INTERVAL

- INTERDOSE INTERVAL (formerly II): interdose interval for doses added using ADDITIONAL DOSES or STEADY-STATE column types

- STEADY STATE (formerly SS): marks that steady-state has been achieved, and will add a predefined number of doses before the actual dose, at interval INTERDOSE INTERVAL, in order to achieve steady-state

Order of events

There are prioritization rules in place in case of various event types occurring at the same time. The order of row numbers in the data set is not important, and same is true for the order of administration and empty/reset macros in model files. The sequence of events will always be the following:- regressors are updated,

- reset done by EVID=3 or EVID=4 is performed,

- dose is administered,

- empty/reset done by macros is performed,

- observation is made.

2.3.Data formatting

The dataset format that is used in Monolix is the same as for the entire MonolixSuite, to allow smooth transitions between applications. In this format, some rules have to be fullfilled, for example:

- Each line corresponds to one individual and one time point.

- Each line can include a single measurement (also called observation), or a dose amount (or both a measurement and a dose amount).

- Dose amount should be indicated for each individual dose in a column AMOUNT, even if it is identical for all.

- Headers are free but there can be only one header line.

If your dataset is not in this format, in most cases, it is possible to format it in a few steps in the data formatting tab, to incorporate the missing information.

In this case, the original dataset should be loaded in the “Format data” box, or directly in the “Data Formatting” tab, instead of the “Data” tab. In the data formatting module, you will be guided to build a dataset in the MonolixSuite format, starting from the loaded csv file. The resulting formatted dataset is then loaded in the Data tab as if you loaded an already-formatted dataset in “Data” directly. Then as for defining any dataset, you can tag columns, accept the dataset, and once accepted, the Filters tab can be used to select only parts of this dataset for analysis. Note that units and filters are neither information to be included in the data file, nor part of the data formatting process.

Jump to:

- Data formatting workflow

- Dataset initialization (mandatory step)

- Selecting header lines or lines to exclude to merge header lines or exclude a line

- Tagging mandatory columns such as ID and TIME

- Initialization example

- Creating occasions from a SORT column to distinguish different sets of measurements within each subject, (eg formulations).

- Selecting an observation type (required to add a treatment)

- Merging observations from several columns

- As observation ids to map them to several outputs of a joint model

- As occasions

- Option “Duplicate information from undefined columns”

- As observation ids to map them to several outputs of a joint model

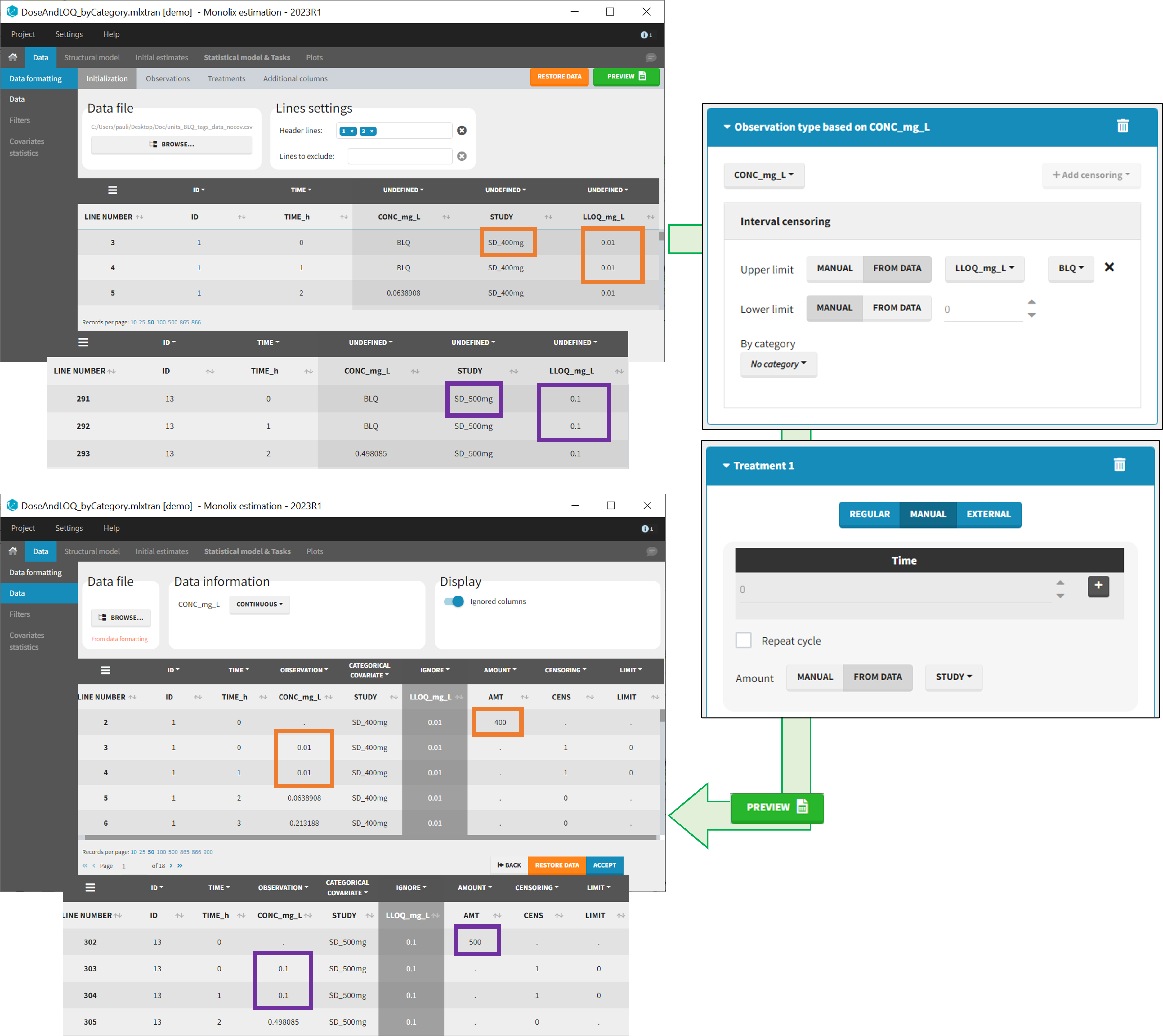

- Specifying censoring from censoring tags eg “BLQ” instead of a number in an observation column. Demo project DoseAndLOQ_manual.mlxtran

- Adding doses in the dataset Demo project DoseAndLOQ_manual.mlxtran

- Reading censoring limits or dosing information from the dataset “by category” or “from data”. Demo projects DoseAndLOQ_byCategory.mlxtran and DoseAndLOQ_fromData.mlxtran

- Creating occasions from dosing intervals to analyze separately the measurements following different doses.Demo project doseIntervals_as_Occ.mlxtran

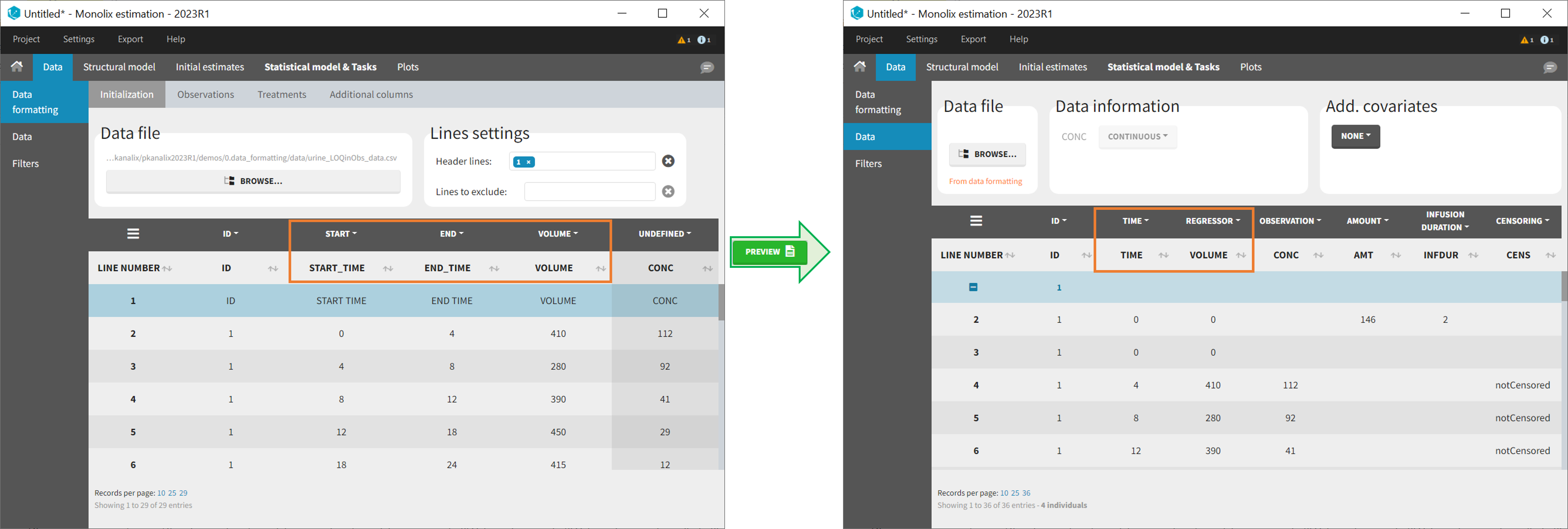

- Handling urine data to merge start and end times in a single column.

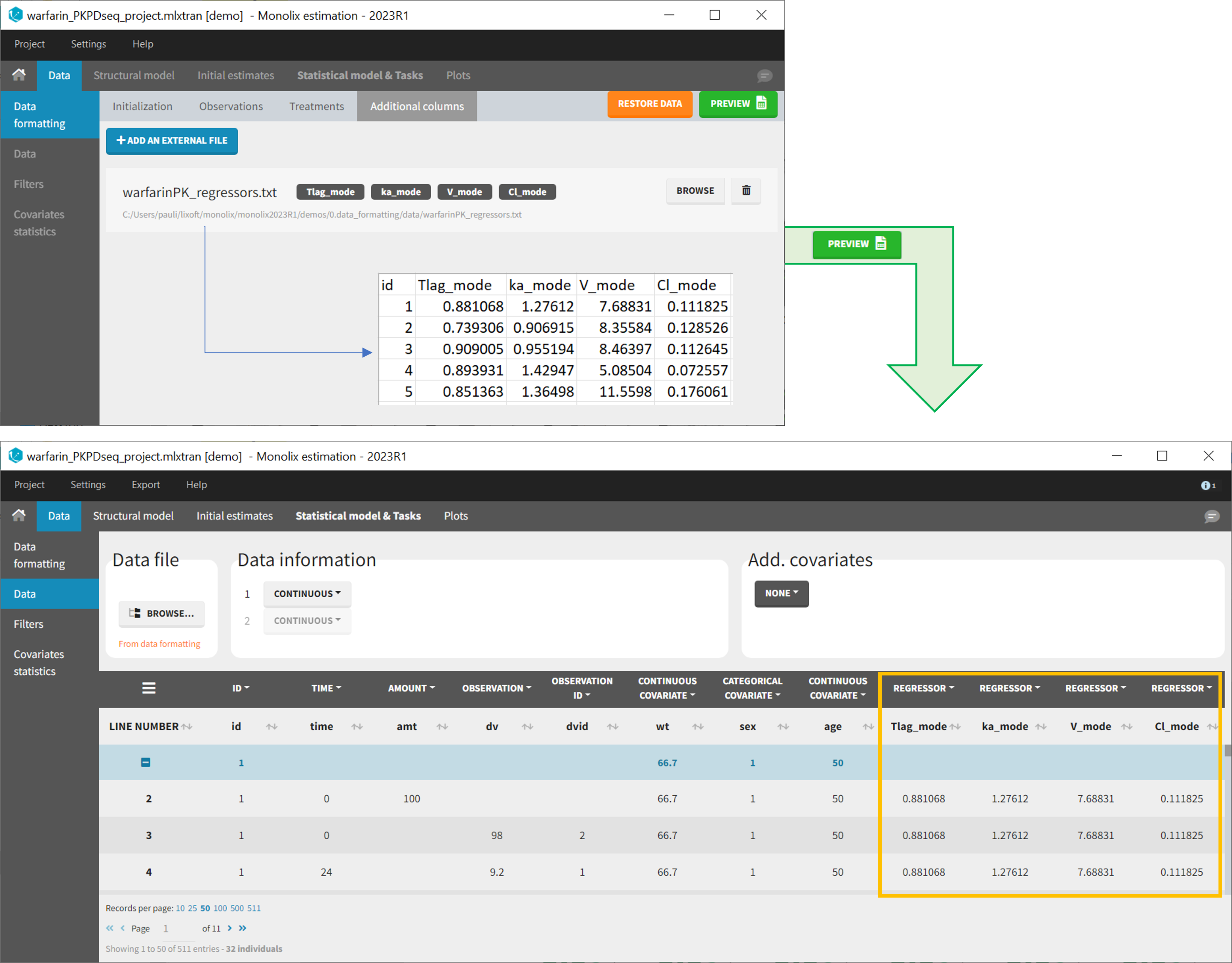

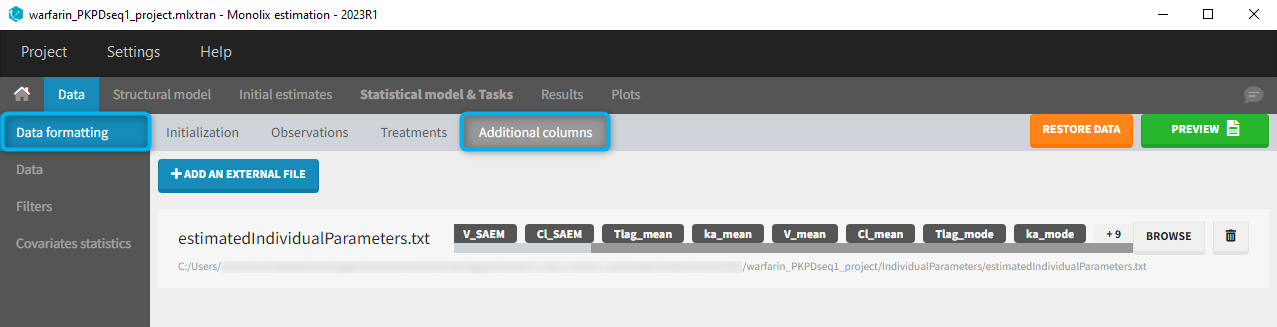

- Adding new columns from an external file, eg new covariates, or individual parameters estimated in a previous analysis. Demo warfarin_PKPDseq_project.mlxtran

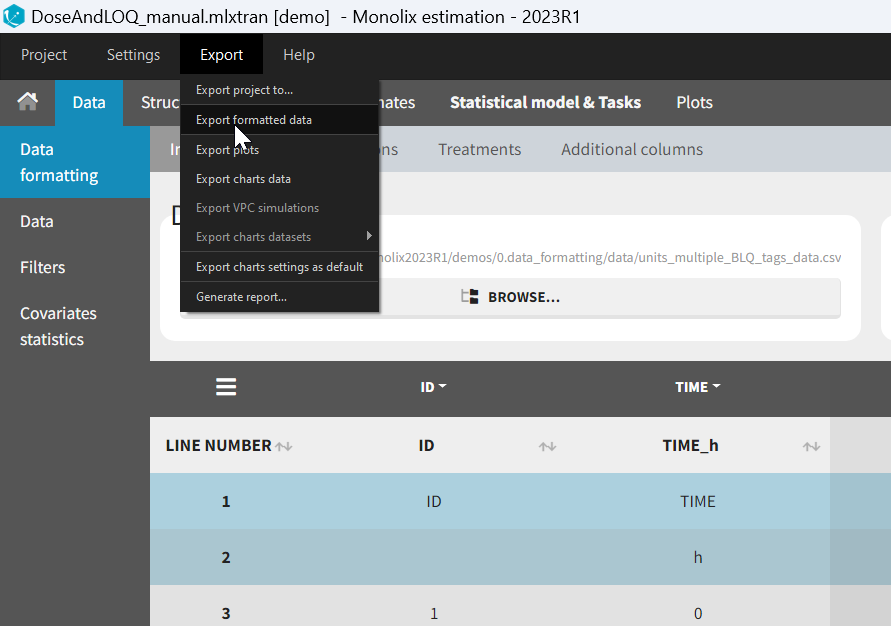

- Exporting the formatted dataset

1. Data formatting workflow

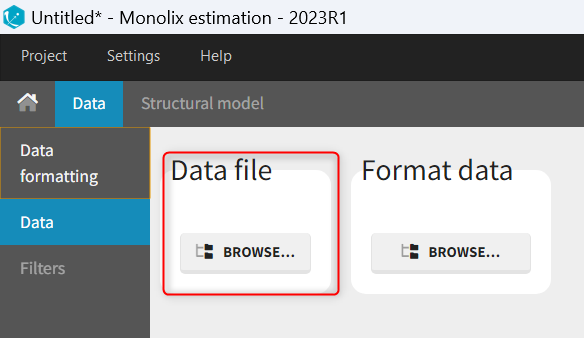

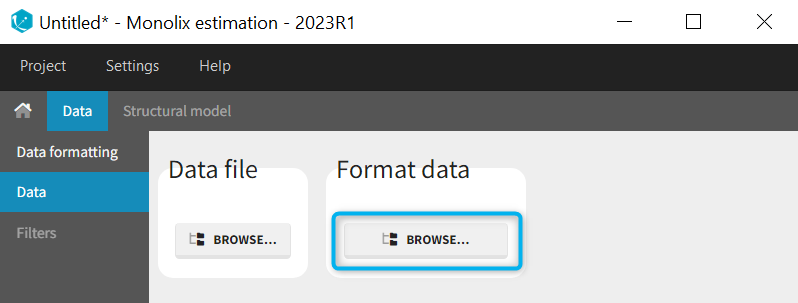

When opening a new project, two Browse buttons appear. The first one, under “Data file”, can be used to load a dataset already in a MonolixSuite-standard format, while the second one, under “Format data”, allows to load a dataset to format in the Data formatting module.

When opening a new project, two Browse buttons appear. The first one, under “Data file”, can be used to load a dataset already in a MonolixSuite-standard format, while the second one, under “Format data”, allows to load a dataset to format in the Data formatting module.

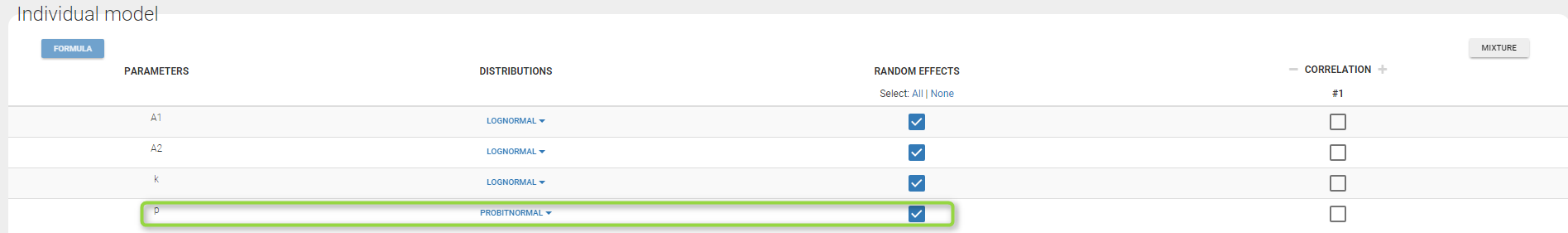

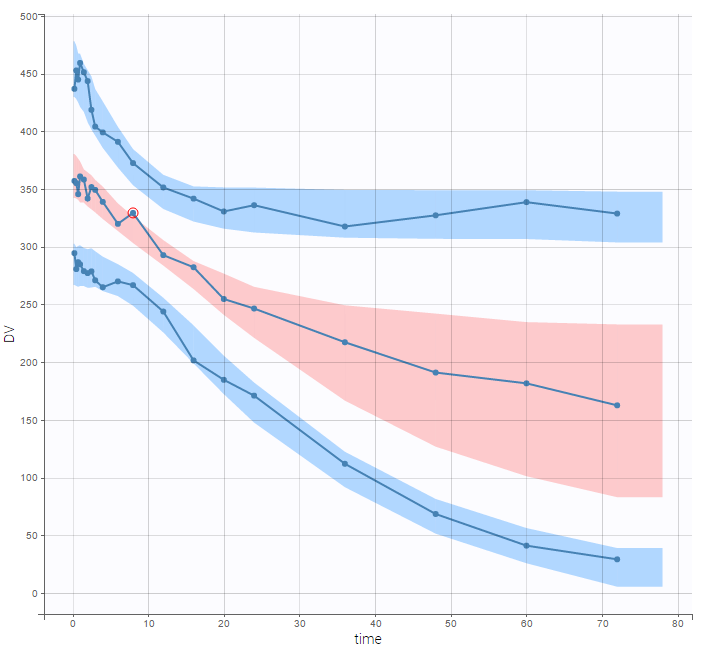

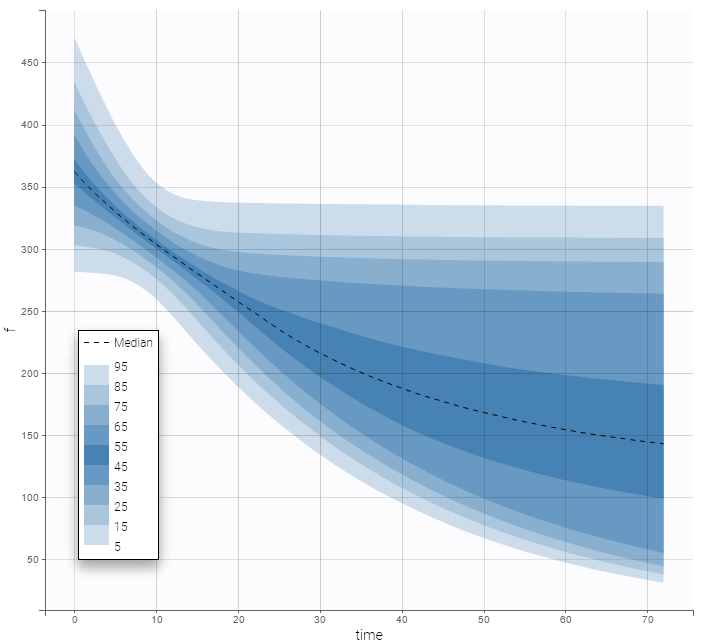

After loading a dataset to format, data formatting operations can be specified in several subtabs: Initialization, Observations, Treatments and Additional columns.

- Initialization is mandatory and must be filled before using the other subtabs.

- Observations is required to enable the Treatments tab.

After Initialization has been validated by clicking on “Next”, a button “Preview” is available from any subtab to view in the Data tab the formatted dataset based on the formatting operations currently specified.

2. Dataset initialization

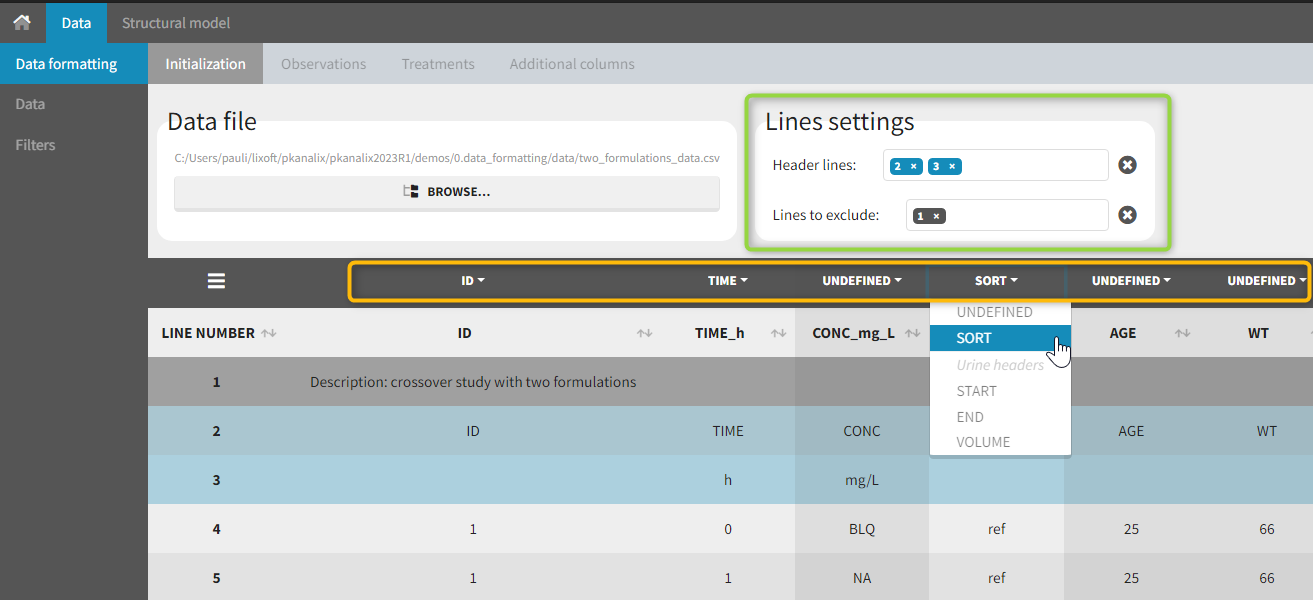

The first tab in Data formatting is named Initialization. This is where the user can select header lines or lines to exclude (in the blue area on the screenshot below) or tag columns (in the yellow area).

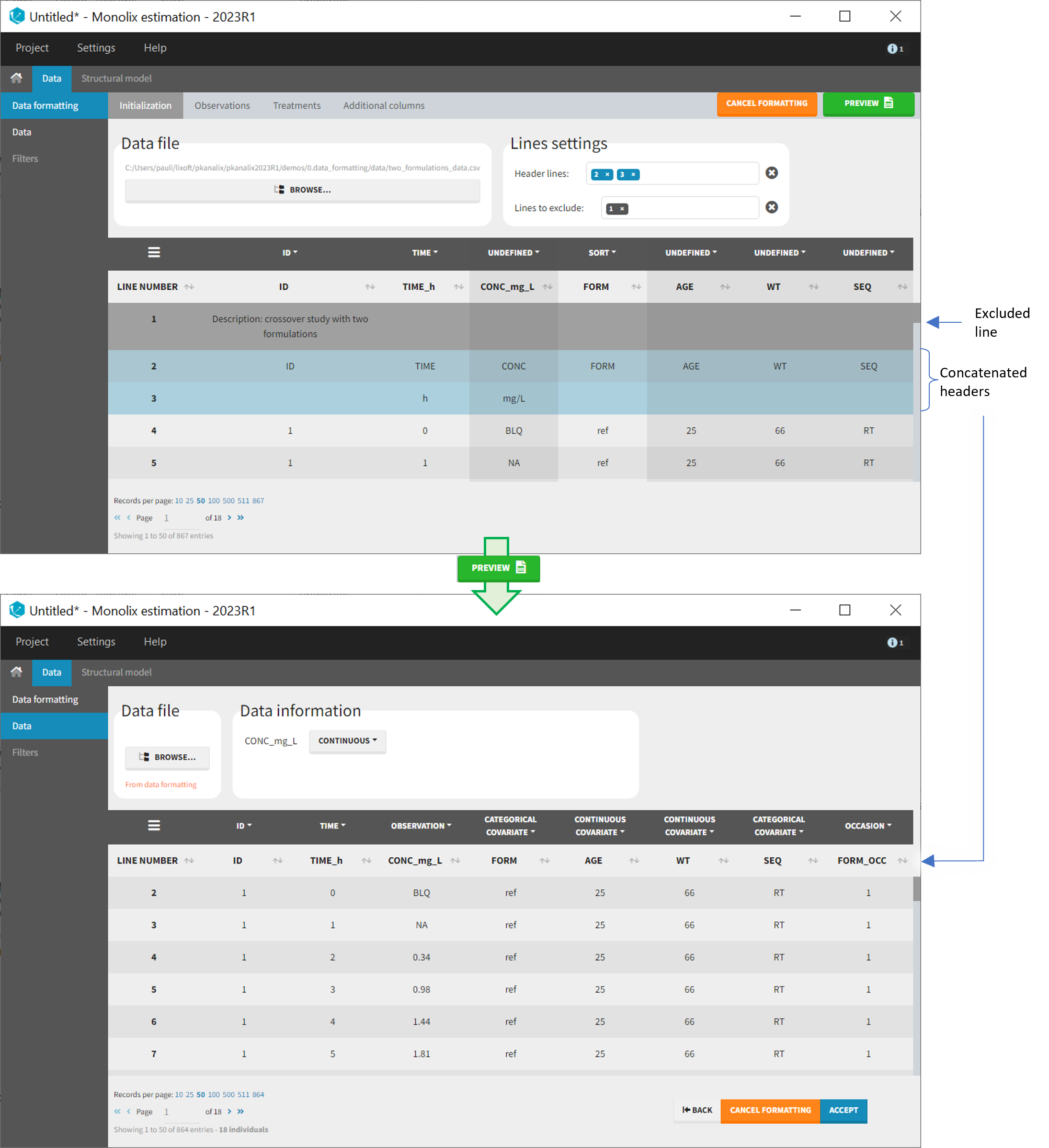

Selecting header lines or lines to exclude

These settings should contain line numbers for lines that should be either handled as column headers or that should be excluded.

- Header lines: one or several lines containing column header information. By default, the first line of the dataset is selected as header. If several lines are selected, they are merged by data formatting into a single line, concatenating the cells in each column.

- Lines to exclude (optional): lines that should be excluded from the formatted dataset by data formatting.

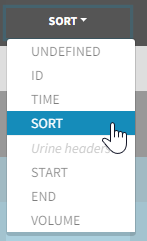

Tagging mandatory columns

Only the columns corresponding to the following tabs must be tagged in Initialization, while all the other columns should keep the default UNDEFINED tag:

- ID (mandatory): subject identifiers

- TIME (mandatory): the single time column

- SORT (optional): one or several columns containing SORT variables can be tagged as SORT. Occasions based on these columns will be created in the formatted dataset as described in Section 3.

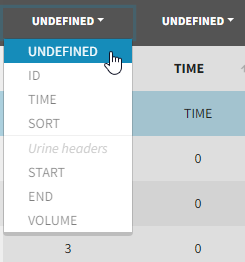

- START, END and VOLUME (mandatory in case of urine data): these column tags replace the TIME tag in case of urine data, if the urine collection time intervals are encoded in the dataset with two time columns for the start and end times of the intervals. In that case there should also be a column with the urine volume in each interval. See Section 10 for more details.

Initialization example

- demo CreateOcc_AdmIdbyCategory.pkx (Monolix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix. The screenshot below focuses on the formatting initialization and excludes other elements present in the demo):

In this demo the first line of the dataset is excluded because it contains a description of the study. The second line contains column headers while the third line contains column units. Since the MonolixSuite-standard format allows only a single header line, lines 2 and 3 are merged together in the formatted dataset.

3. Creating occasions from a SORT column

A SORT variable can be used to distinguish different sets of measurements (usually concentrations) within each subject, that should be analyzed separately by Monolix (for example: different formulations given to each individual at different periods of time, or multiple doses where concentration profiles are available to be analyzed following several doses).

In Monolix, these different sets of measurements must be distinguished as OCCASIONS (or periods of time), via the OCCASION column-type. However, a column tagged as OCCASION can only contain integers with occasion indexes. Thus, if a column with a SORT variable contains strings, its format must be adapted by Data formatting, in the following way:

- the user must tag the column as SORT in the Initialization subtab of Data formatting,

- the user validates the Initialization with “Next”, then clicks on “Preview” (after optionally defining other data formatting operations),

- the formatted data is shown in Data: the column tagged as SORT is automatically duplicated. The original column is automatically tagged as CATEGORICAL COVARIATE in Data, while the duplicated column, which has the same name appended with “_OCC”, is tagged as OCCASION. This column contains occasion indexes instead of strings.

Example:

- demo CreateOcc_AdmIdbyCategory.pkx (PKanalix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix. The screenshot below focuses on the formatting of occasions and excludes other elements present in the demo):

The image below shows lines 25 to 29 from the dataset from the CreateOcc_AdmIdbyCategory.pkx demo, where covariate columns have been removed to simplify the example. This dataset contains two sets of concentration measurements for each individual, corresponding to two different drug formulations administered on different periods. The sets of concentrations are distinguished with the FORM column, which contains “ref” and “test” categories (reference/test formulations). The column is tagged as SORT in Data formatting Initialization. After clicking on “Preview”, we can see in the Data tab that a new column named FORM_OCC has been created with occasion indexes for each individual: for subject 1, FORM_OCC=1 corresponds to the reference formulation because it appears first in the dataset, and FORM_OCC=2 corresponds to the test formulation because it appears in second in the dataset.

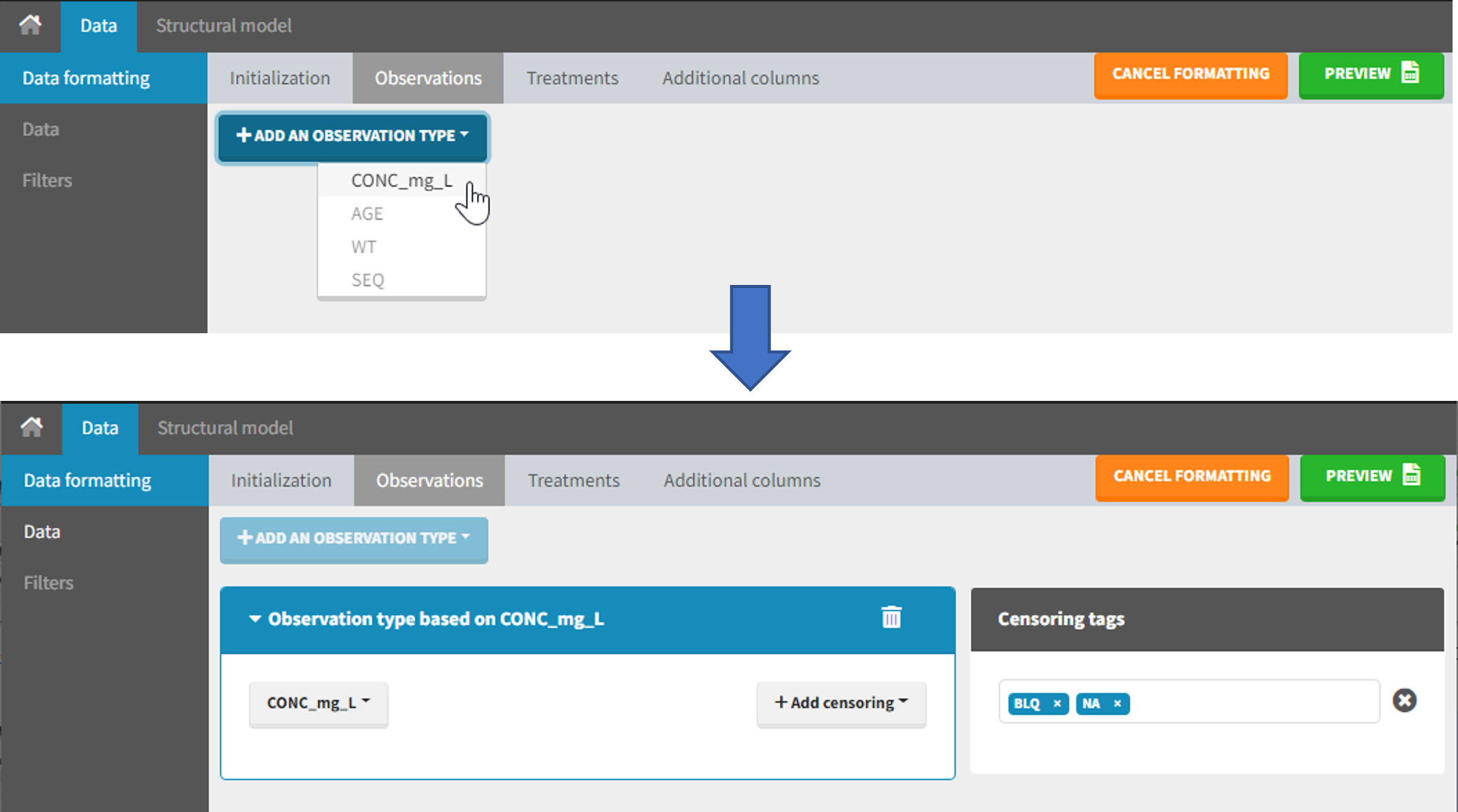

4. Selecting an observation type

The second subtab in Data formatting allows to select one or several observation types. An observation type corresponds to a column of the dataset, that contains a type of measurements (usually drug concentrations, but it can also be PD measurements for example). Only columns that have not been tagged as ID, TIME or SORT are available as observation type.

This action is optional and can have several purposes:

- If doses must be added by Data formatting (see Section 7), specifying the column containing observations is mandatory, to avoid duplicating observations on new dose lines.

- If several observation types exist in different columns (for example: concentrations for different analytes, or measurements for PK and PD), they must be specified in Data formatting to be merged into a single observation column (see Section 5).

- In the MonolixSuite-standard format, the column containing observations can only contain numbers, and no string except “.” for a missing observation. Thus if this column contains strings in the original dataset, it must be adapted by Data formatting, with two different cases:

- if the strings are tags for censored observations (usually BLQ: below the limit of quantification), they can be specified in Data formatting to adapt the encoding of the censored observations (see Section 6),

- any other string in the column is automatically replaced by “.” by Data formatting.

5. Merging observations from several columns

The MonolixSuite-standard format allows a single column containing all observations (such as concentrations or PD measurements). Thus if a dataset contains several observation types in different columns (for example: concentrations for different analytes, or measurements for PK and PD), they must be specified in Data formatting to be merged into a single observation column.

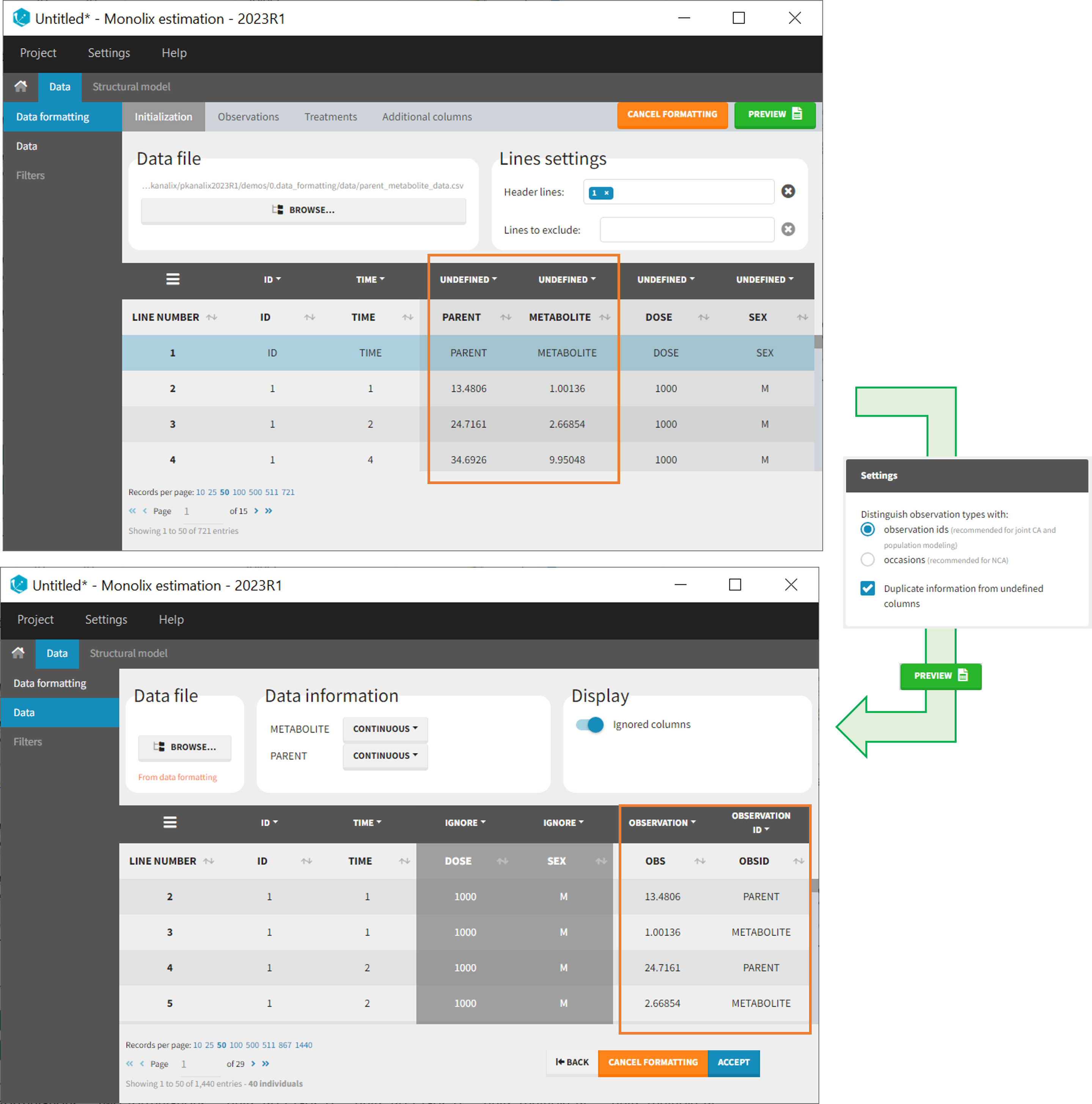

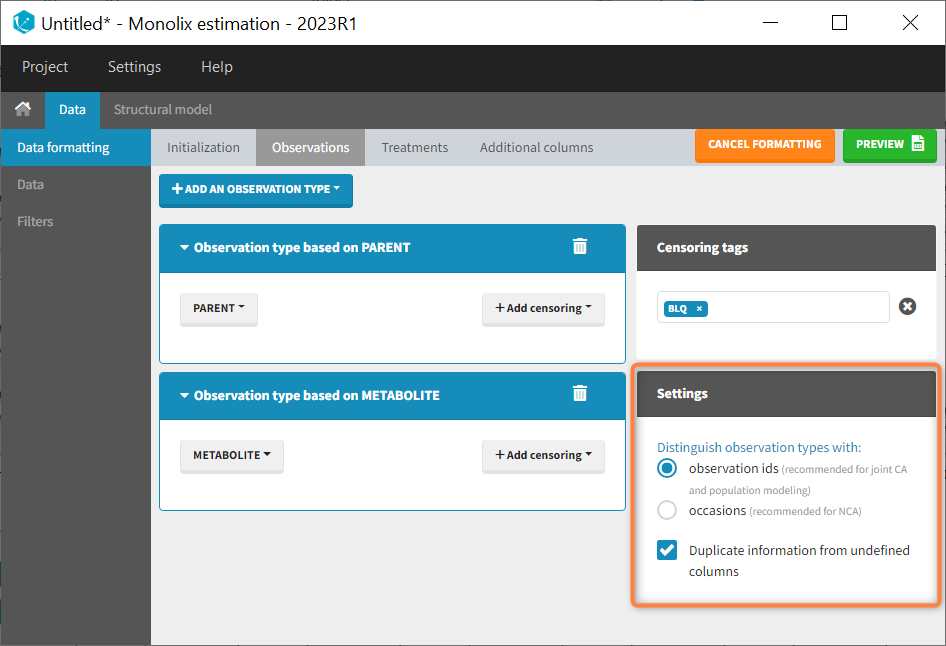

In that case, different settings can be chosen in the area marked in orange in the screenshot below:

- The user must choose between distinguishing observation types with observation ids or occasions.

- The user can unselect the option “Duplicate information from undefined columns”.

As observation ids

After selecting the “Distinguish observation types with: observation ids” option and clicking “Preview,” the columns for different observation types are combined into a single column called “OBS.” Each row of the dataset is duplicated for each observation type, with one value per observation type. Additionally, an “OBSID” column is created, with the name of the observation type corresponding to the measurement on each row.

This option is recommended for joint modeling of observation types, such as CA in Monolix or population modeling in Monolix. It is important to note that NCA cannot be performed on two different observation ids simultaneously, so it is necessary to choose one observation id for the analysis.

Example:

- demo merge_obsID_ParentMetabolite.pkx PKanalix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix. The screenshot below focuses on the formatting of observations and excludes other elements present in the demo):

This demo involves two columns that contain drug parent and metabolite concentrations. When merging both observation types with observation ids, a new column called OBSID is generated with categories labeled as “PARENT” and “METABOLITE.”

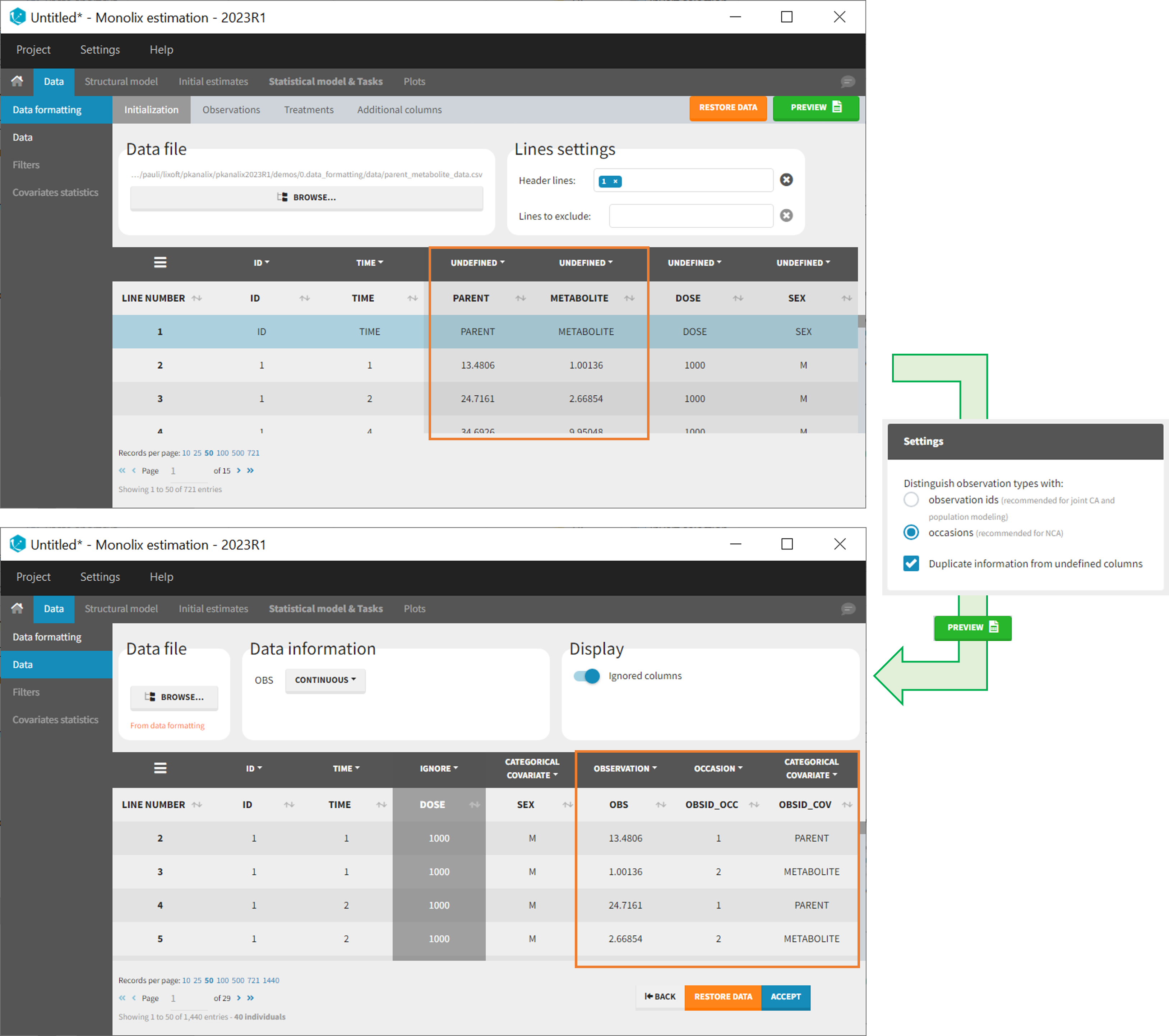

As occasions

After selecting the “Distinguish observation types with: occasions” option and clicking “Preview,” the columns for different observation types are combined into a single column called “OBS.” Each row of the dataset is duplicated for each observation type, with one value per observation type. Additionally, two columns are created: an “OBSID_OCC” column with the index of the observation type corresponding to the measurement on each row, and an “OBSID_COV” with the name of the observation type.

This option is recommended for NCA, which can be run on different occasions for each individual. However, joint modeling of the observation types with CA or population modeling with Monolix cannot be performed with this option.

Example:

- demo merge_occ_ParentMetabolite.pkx (PKanalix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix. The screenshot below focuses on the formatting of observations and excludes other elements present in the demo):

This demo involves two columns that contain drug parent and metabolite concentrations. When merging both observation types with occasions, two new columns called OBSID_OCC and OBSID_COV are generated with OBSID_OCC=1 corresponding to OBSID_COV=”PARENT” catand OBSID_OCC=2 corresponding to OBSID_COV=”METABOLITE.”

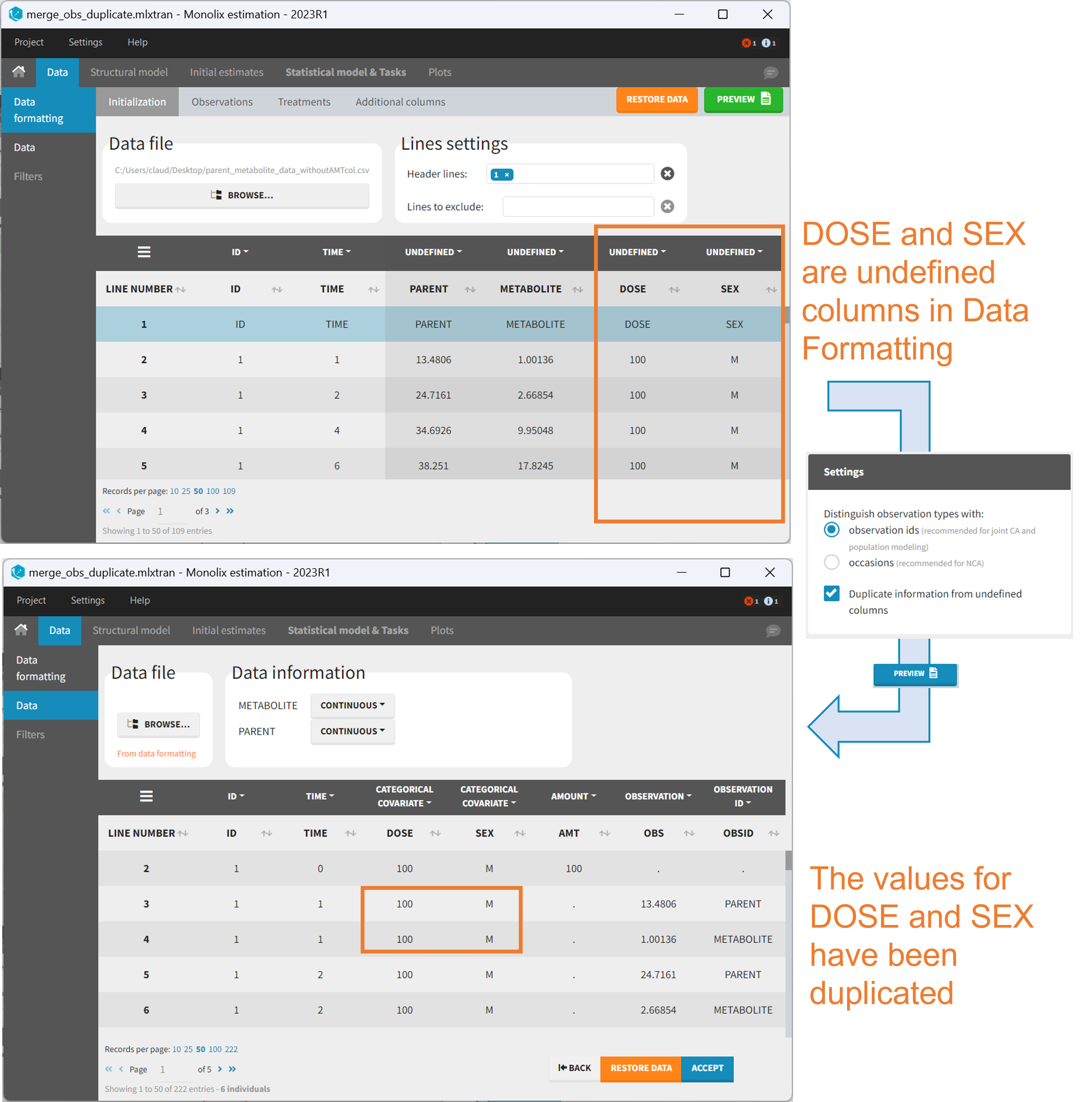

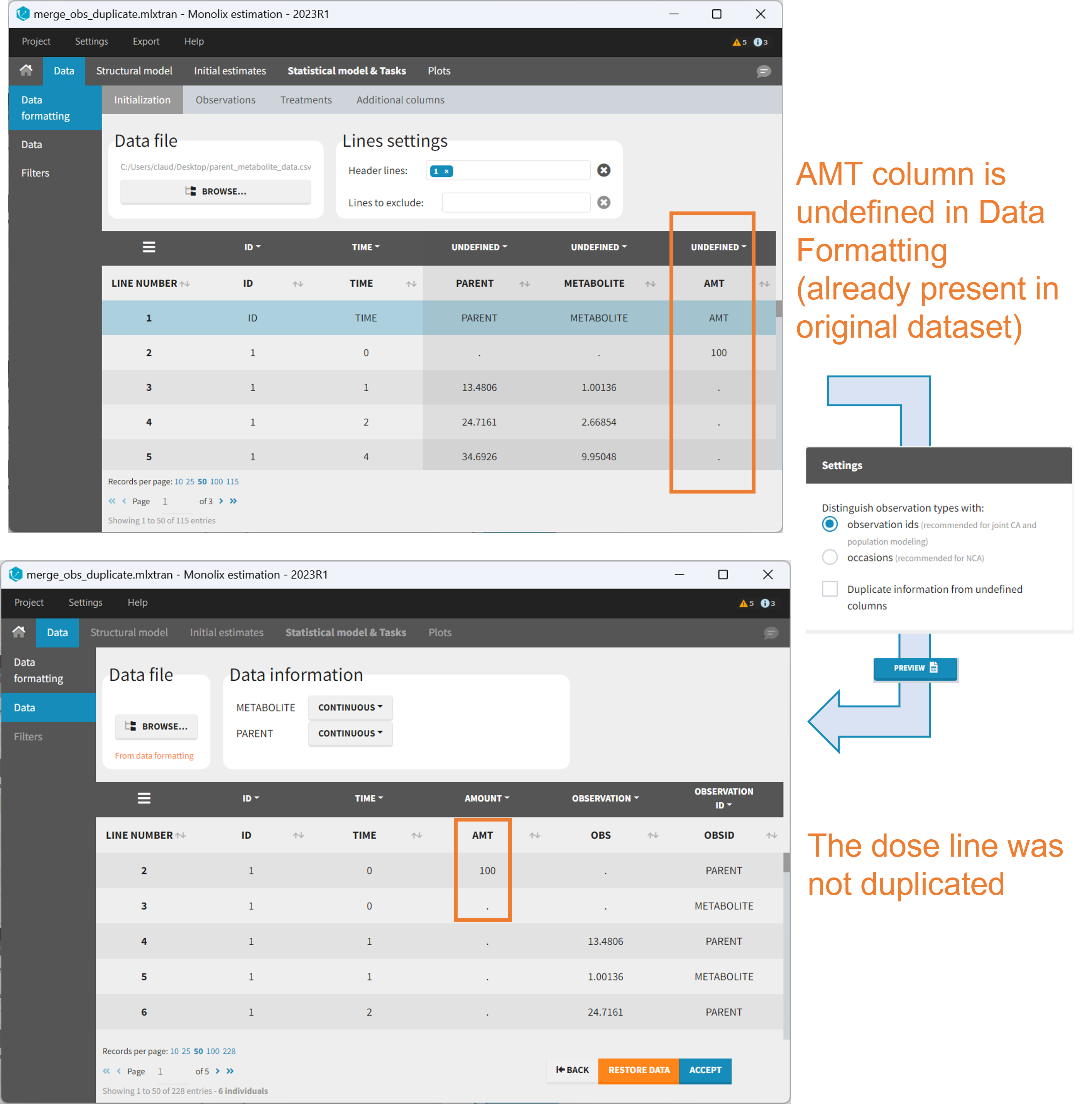

Duplicate information from undefined columns

When merging two observation columns into a single column, all other columns will see their lines duplicated. The data formatting will know how to treat columns which have been tagged in the Initialization tab, but not the other columns (header “UNDEFINED”) which are not used for data formatting. A checkbox enables to decide if the information from these columns should be duplicated on the new lines, or if “.” should be used instead. The default option is to duplicate information, because in general, the undefined columns correspond to covariates with one value per individual, so this value is the same for the two lines that correspond to the same id.

It is rare that you need to uncheck this box. An example where you should not duplicate the information is if you already have a column Amount in the MonolixSuite format, so with a dose amount only at the dosing time, and “.” everywhere else. If you do not want to specify amount again in data formatting, and simply want to merge observation columns as observation ids, you should not duplicate the lines of the Amount column which is undefined. Indeed, the dose amounts have been administered only once.

6. Specifying censoring from censoring tags

In the MonolixSuite-standard format, censored observations are encoded with a 1or -1 flag in a column tagged as CENSORING in the Data tab, while exact observations have a 0 flag in that column. In addition, on rows for censored observations, the LOQ is indicated in the observation column: it is the LLOQ (lower limit of quantification) if CENSORING=1 or the ULOQ (upper limit of quantification) if CENSORING=-1. Finally, to specify a censoring interval, an additional column tagged as LIMIT in the Data tab must exist in the dataset, with the other censoring bound.

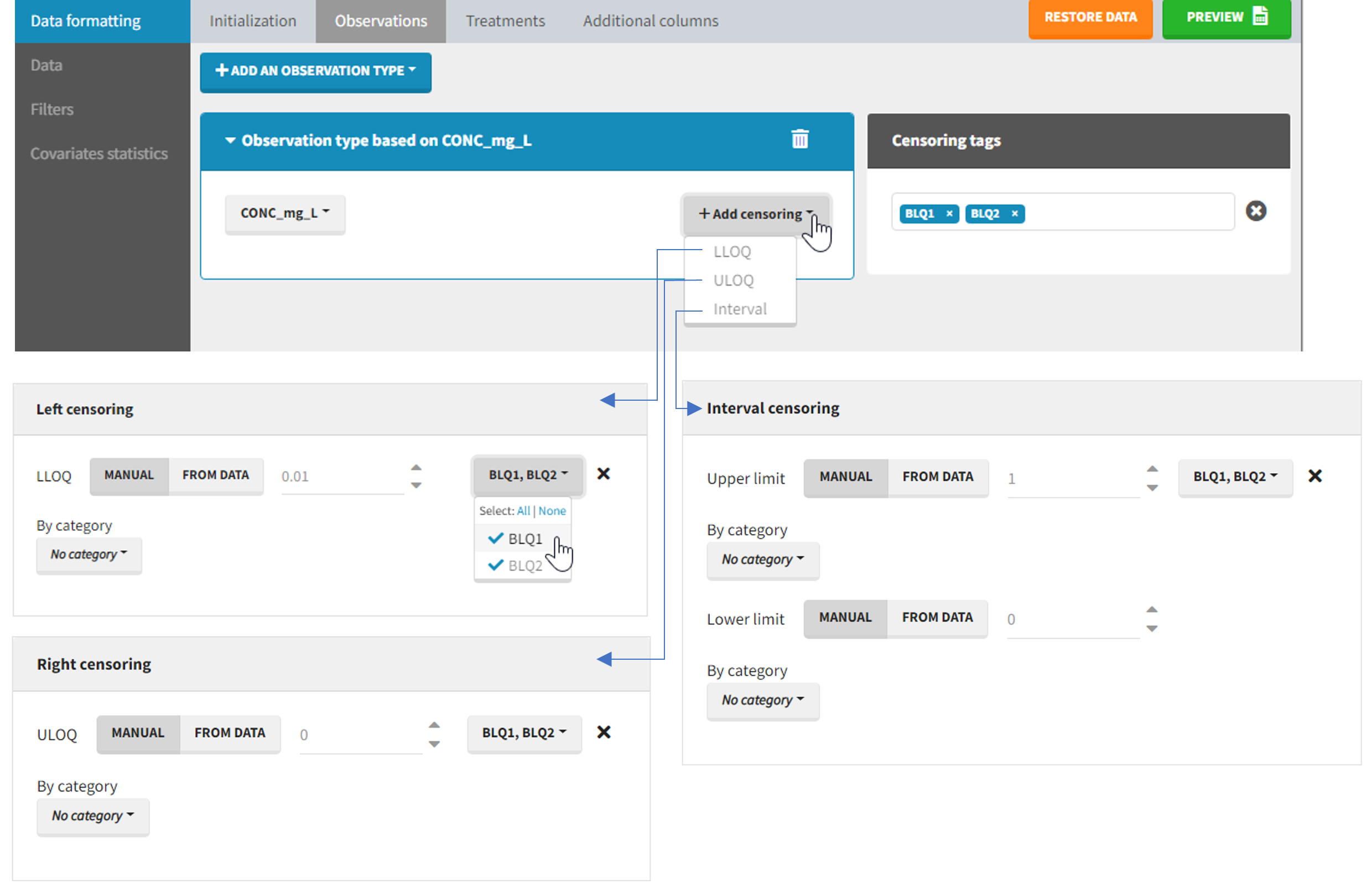

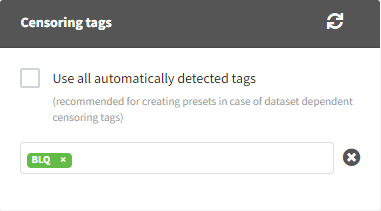

The Data Formatting module can take as input a dataset with censoring tags directly in the observation column, and adapt the dataset format as described above. After selecting one or several observation types in the Observations subtab (see Section 4), all strings found in the corresponding columns are displayed in the “Censoring tags” on the right of the observation types. If at least one string is found, the user can then define some censoring associated with an observation type and with one or several censoring tags with the button “Add censoring”. 3 types of censoring can be defined:

- LLOQ: this corresponds to left-censoring, where the censored observation is below a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), that must specified by the user. In that case Data Formatting replaces the censoring tags in the observation column by the LLOQ, and creates a new CENS column tagged as CENSORING in the Data tab, with 1 on rows that had censoring tags before formatting, and 0 on other rows.

- ULOQ: this corresponds to right-censoring, where the censored observation is above an upper limit of quantification (ULOQ), that must specified by the user. Here Data Formatting replaces the censoring tags in the observation column by the ULOQ, and creates a new CENS column tagged as CENSORING in the Data tab, with -1 on rows that had censoring tags before formatting, and 0 on other rows.

- Interval: this is for interval-censoring, where the user must specify two bound of a censoring interval, to which the censored observation belong. Data Formatting replaces the censoring tags in the observation column by the upper bound of the interval, and creates two new columns: a CENS column tagged as CENSORING in the Data tab, with 1 on rows that had censoring tags before formatting, and 0 on other rows, and a LIMIT column with the lower bound of the censoring interval on rows that had censoring tags before formatting, and “.” on other rows.

For each type of censoring, available options to define the limits are:

- “Manual“: limits are defined manually, by entering the limit values for all censored observations.

- “By category“: limits are defined manually for different categories read from the dataset.

- “From data“: limits are directly read from the dataset.

The options “by category” and “from data” are described in detail in Section 8.

Example:

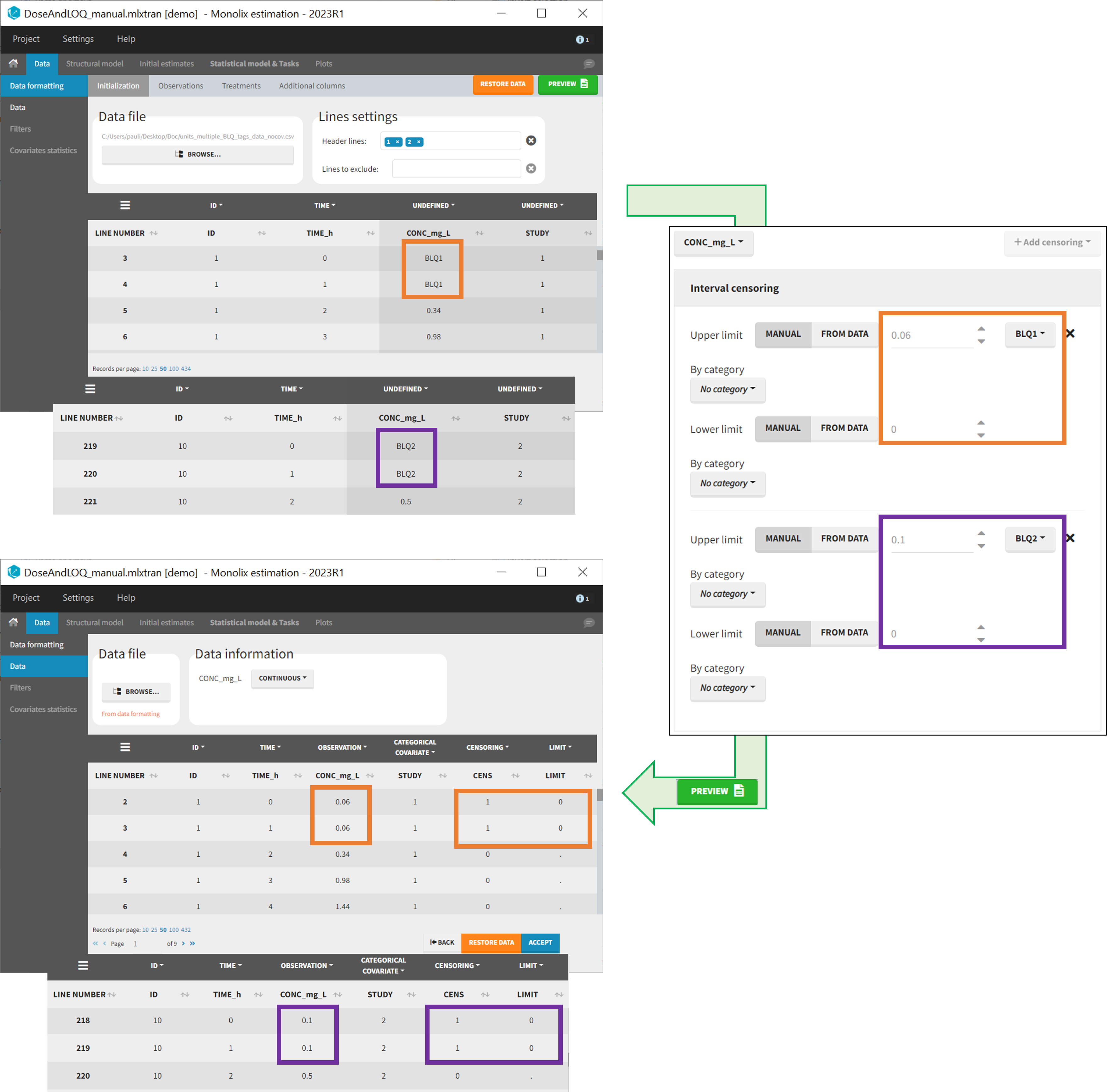

- demo DoseAndLOQ_manual.mlxtran (the screenshot below focuses on the formatting of censored observations and excludes other elements present in the demo):

In this demo there are two censoring tags in the CONC column: BLQ1 (from Study 1) and BLQ2 (from Study 2), that correspond to different LLOQs. An interval censoring is defined for each censoring tag, with manual limits, where LLOQ=0.06 for BLQ1 and LLOQ=0.1 for BLQ2, and the lower limit of the censoring interval being 0 in both cases.

7. Adding doses in the dataset

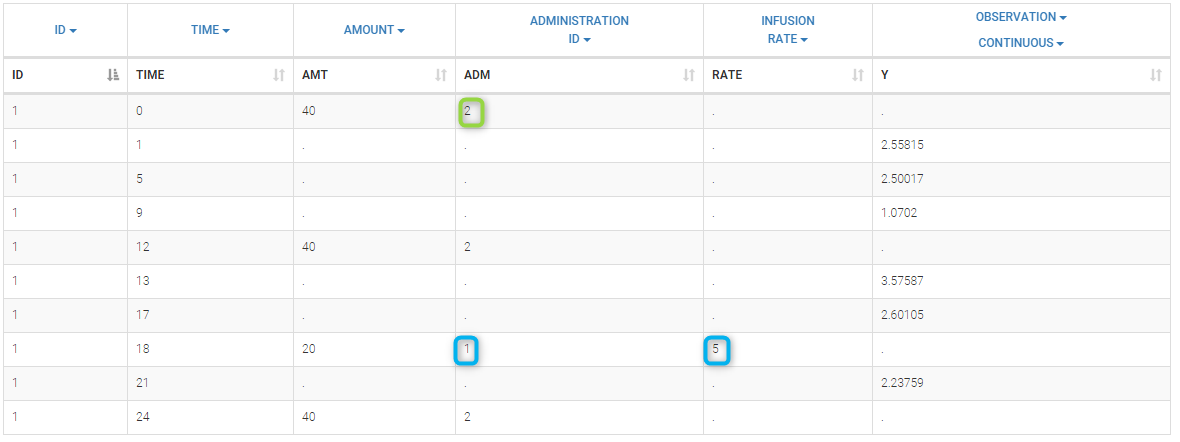

Datasets in MonolixSuite-standard format should contain all information on doses, as dose lines. An AMOUNT column records the amount of the administrated doses on dose-lines, with “.” on response-lines. In case of infusion, an INFUSION DURATION or INFUSION RATE column records the infusion duration or rate. If there are several types of administration, an ADMINISTRATION ID column can distinguish the different types of doses with integers.

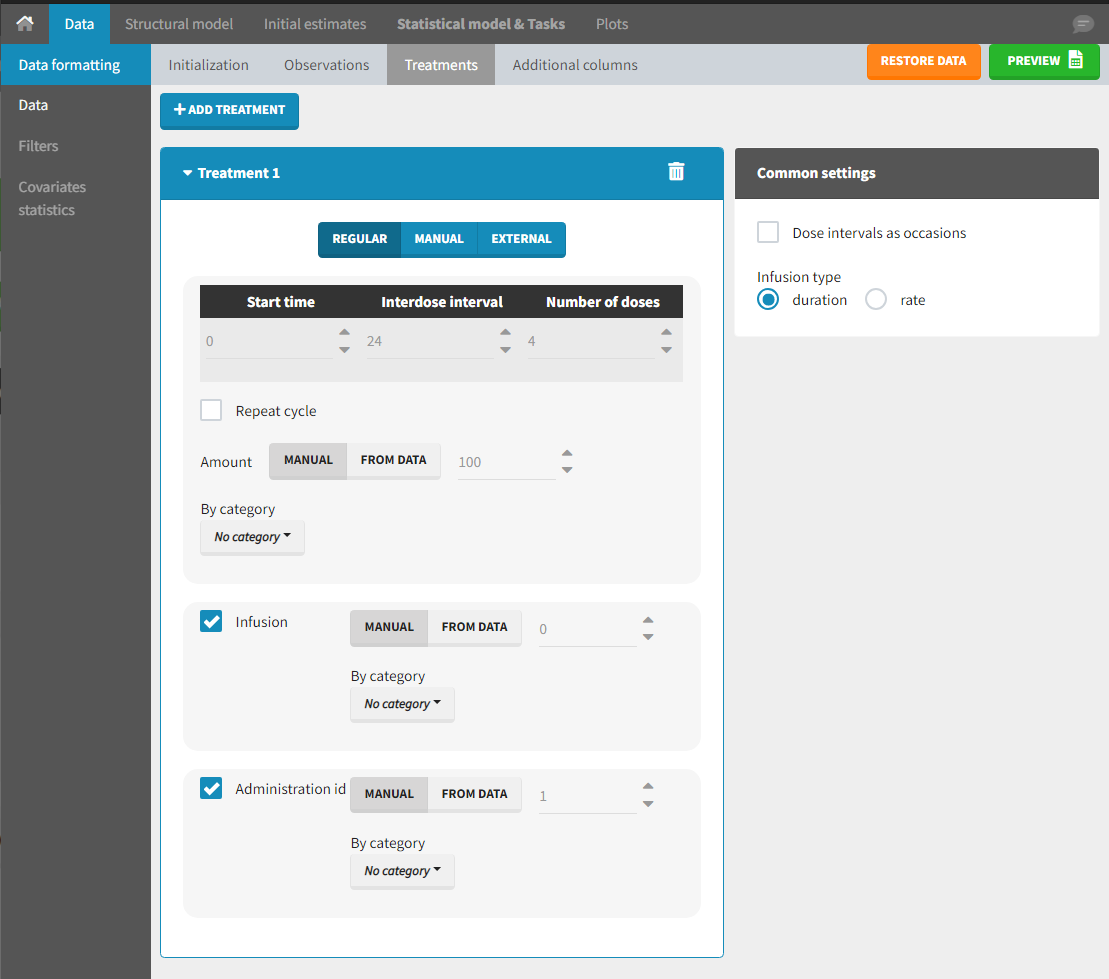

If doses are missing from a dataset, the Data Formatting module can be used to add dose lines and dose-related columns: after initializing the dataset, the user can specify one or several treatments in the Treatments subtab. The following operations are then performed by Data Formatting:

- a new dose line is inserted in the dataset for each defined dose, with the dataset sorted by subject and times. On such a dose line, the values from the next line are duplicated for all columns, except for the observation column in which “.” is used for the dose line.

- A new column AMT is created with “.” on all lines except on dose lines, on which dose amounts are used. The AMT column is automatically tagged as AMOUNT in the Data tab.

- If administration ids have been defined in the treatment, an ADMID column is created, with “.” on all lines except on dose lines, on which administration ids are used. The ADMID column is automatically tagged as ADMINISTRATION ID in the Data tab.

- If an infusion duration or rate has been defined, a new INFDUR (for infusion duration) or INFRATE (for infusion rate) is created, with “.” on all lines except on dose lines. The INFDUR column is automatically tagged as INFUSION DURATION in the Data tab, and the INFRATE column is automatically tagged as INFUSION RATE.

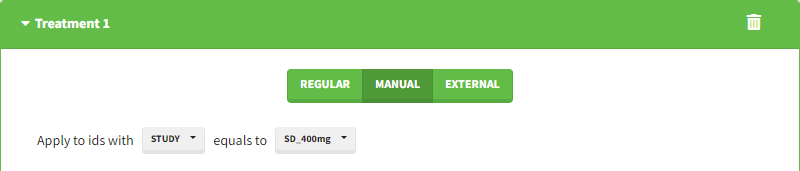

Starting from the 2024R1 version, different dosing schedules can be defined for different individuals, based on information from other columns, which can be useful in cases when different cohorts received different dosing regimens, or when working with data pooled from multiple studies. To define a treatment just for a specific cohort or study, the dropdown on the top of the treatment section can be used:

For each treatment, the dosing schedule can defined as:

- regular: for regularly spaced dosing times, defined with the start time, inter-dose internal, and number of doses. A “repeat cycle” option allows to repeat the regular dosing schedule to generate a more complex regimen.

- manual: a vector of one or several dosing times, each defined manually. A “repeat cycle” option allows to repeat the manual dosing schedule to generate a more complex regimen.

- external: an external text file with columns id (optional), occasions (optional), time (mandatory), amount (mandatory), admid (administration id, optional), tinf or rate (optional), that allows to define individual doses.

While dose amounts, administration ids and infusion durations or rates are defined in the external file for external treatments, available options to define them for treatments of type “manual” or “regular” are:

- “Manual“: this applies the same amount (or administration id or infusion duration or rate) to all doses.

- “By category“: dose amounts (or administration id or infusion duration or rate) are defined manually for different categories read from the dataset.

- “From data“: dose amounts (or administration id or infusion duration or rate) are directly read from the dataset.

The options “by category” and “from data” are described in detail in Section 8.

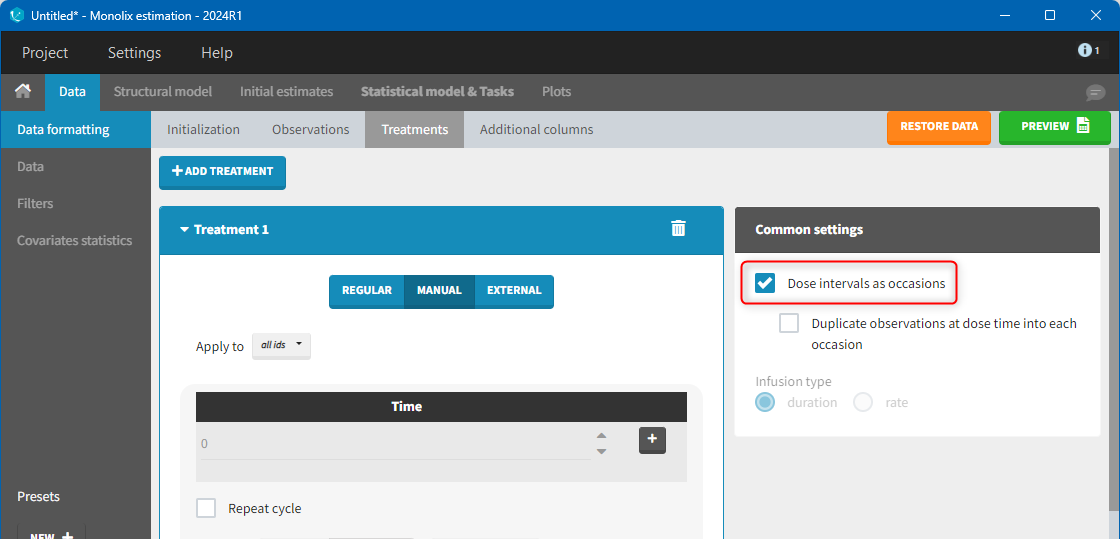

There is a “common settings” panel on the right:

- dose intervals as occasions: this creates a column to distinguish the dose intervals as different occasions (see Section 9).

- infusion type: If several treatments correspond to infusion administration, they need to share the same type of encoding for infusion information: as infusion duration or as infusion rate.

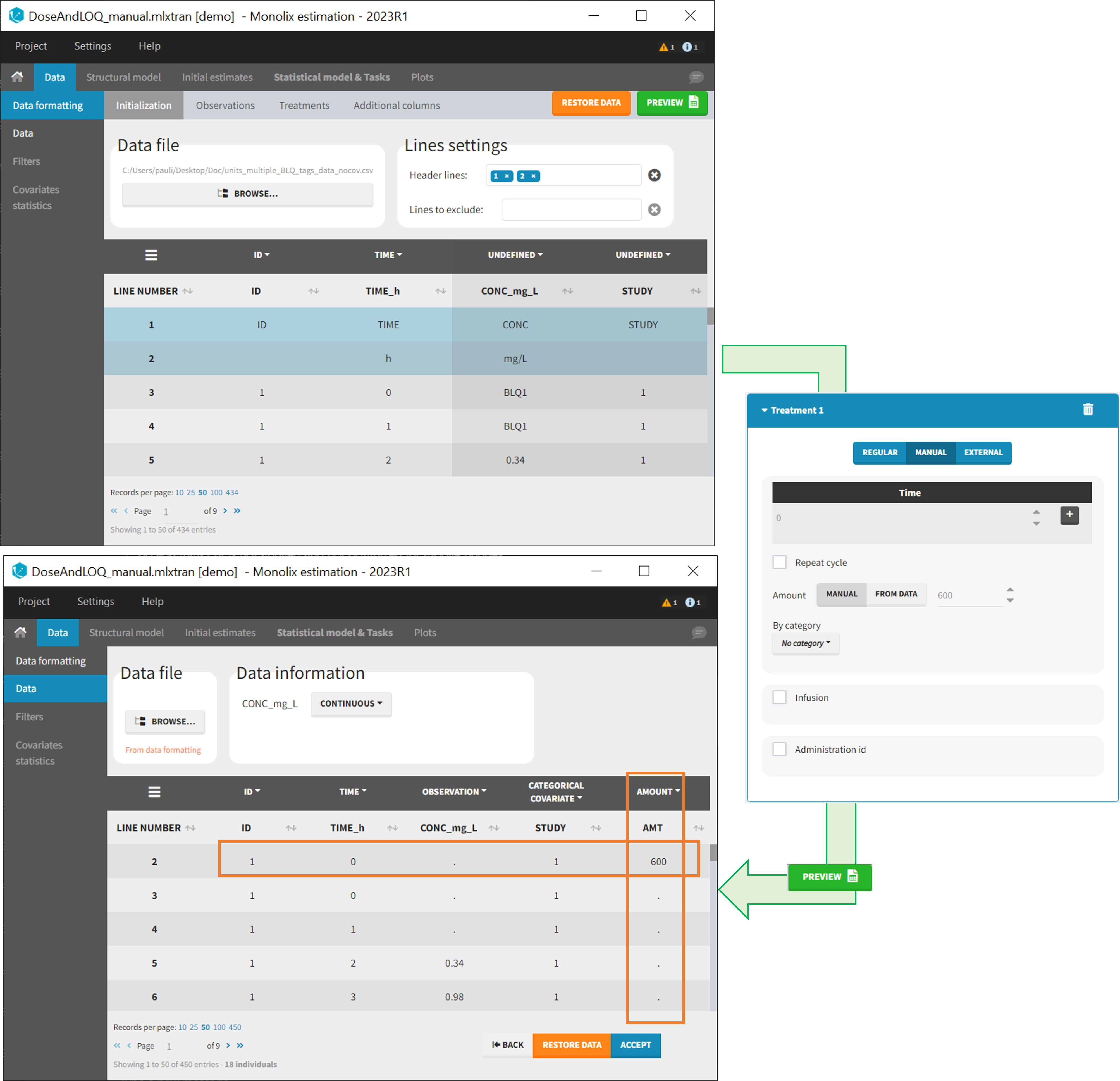

Example:

- demo DoseAndLOQ_manual.mlxtran (the screenshot below focuses on the formatting of doses and excludes other elements present in the demo):

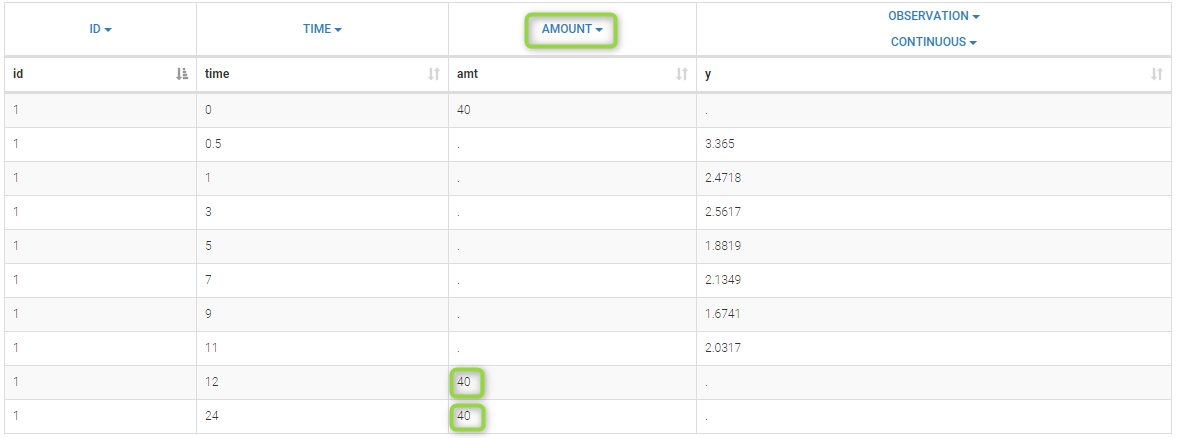

In this demo, doses are initially not included in the dataset to format. A single dose at time 0 with an amount of 600 is added for each individual by Data Formatting. This creates a new AMT column in the formatted dataset, tagged as AMOUNT.

8. Reading censoring limits or dosing information from the dataset

When defining censoring limits for observations (see Section 6) or dose amounts, administration ids, infusion duration or rate for treatments (see Section 7), two options allow to define different values for different rows, based on information already present in the dataset: “by category” and “from data”.

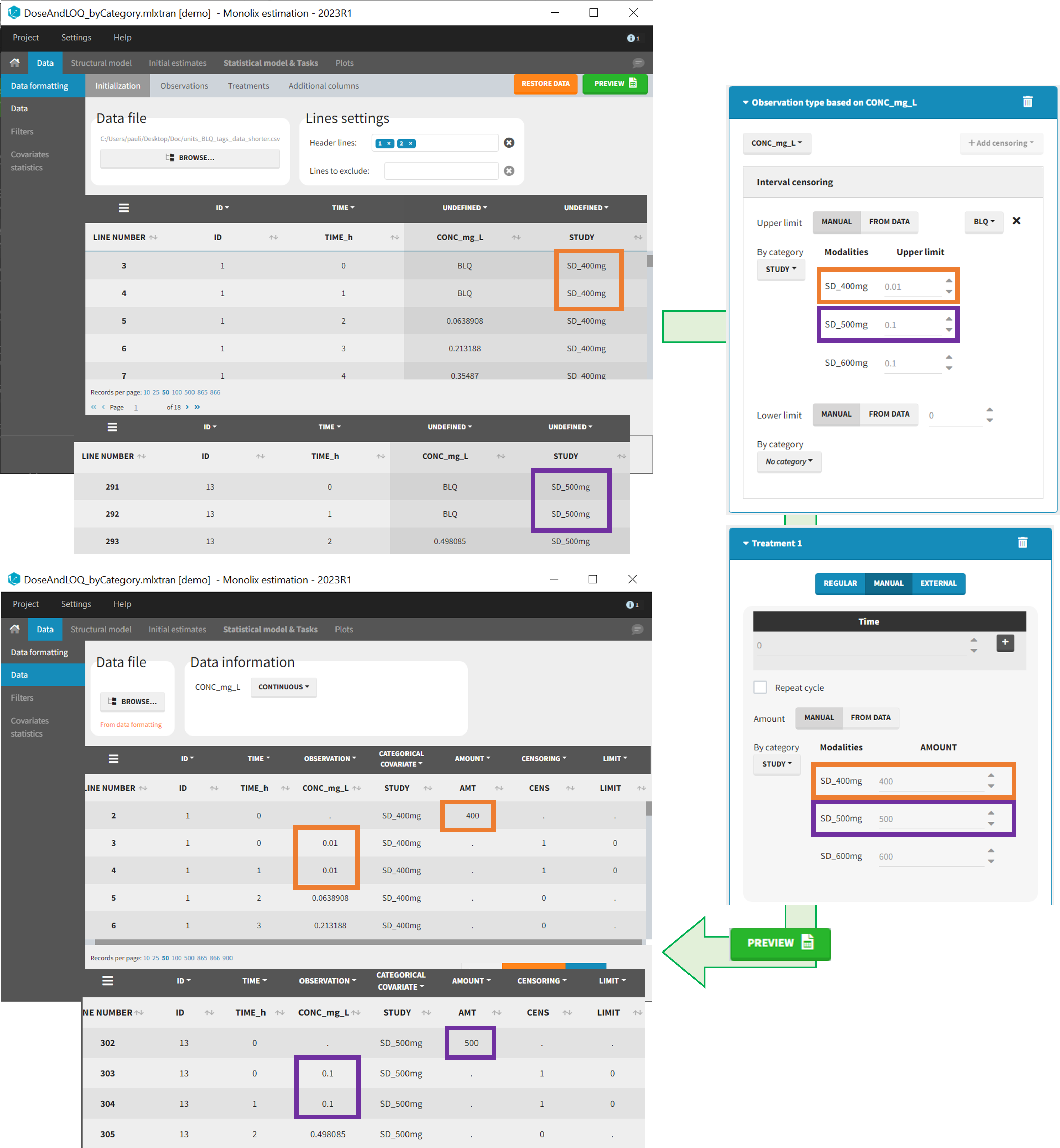

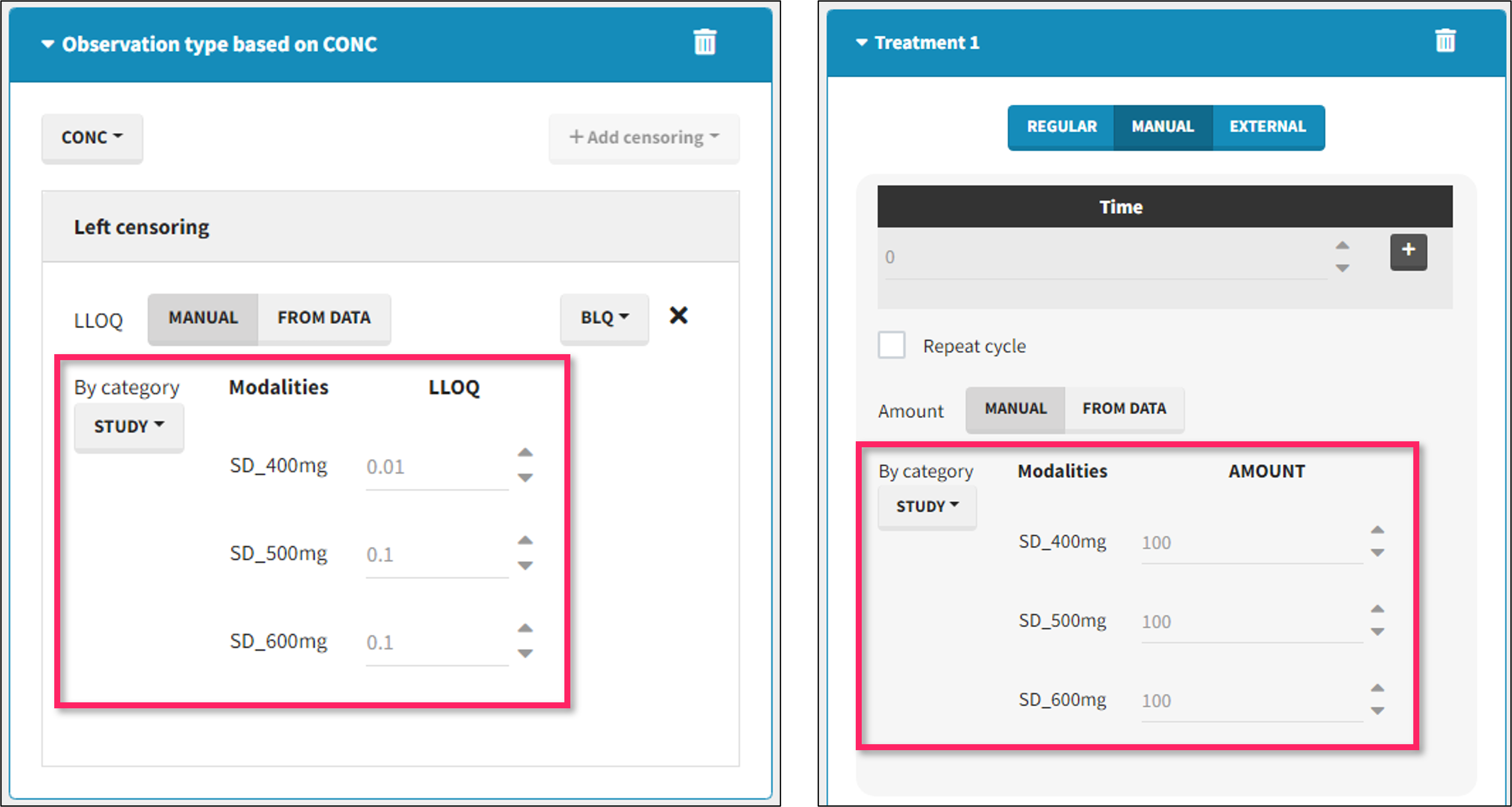

By category

It is possible to define manually different censoring limits, dose amounts, administration ids, infusion durations, or rates for different categories within a dataset’s column. After selecting this column in the “By category” drop-down menu, the different modalities in the column are displayed and a value must be manually assigned each modality.

- For censoring limits, the censoring limit used to replace each censoring tag depends on the modality on the same row.

- For doses, the value chosen for the newly created column (AMT for amount, ADMID for administration id, INFDUR for infusion duration, INFRATE for infusion rate) on each new dose line depends on the modality on the first row found in the dataset for the same individual and the same time as the dose, or the next time if there is no line in the initial dataset at that time, or the previous time if no time is found after the dose.

Example:

- demo DoseAndLOQ_byCategory.mlxtran (the screenshot below focuses on the formatting of doses and excludes other elements present in the demo):

In this demo there are three studies distinguished in the STUDY column with the categories “SD_400mg”, “SD_500mg” and “SD_600mg”. In Data Formatting, a single dose is manually defined at time 0 for all individuals, with different amounts depending the STUDY category. In addition, censoring interval is defined for the censoring tags BLQ, with an upper limit of the censoring interval (lower limit of quantification) that also depends on the STUDY category. Three new columns – AMT for dose amounts, CENS for censoring tags (0 or 1), and LIMIT for the lower limit of the censoring intervals – are created by Data Formatting. A new dose line is then inserted at time 0 for each individual.

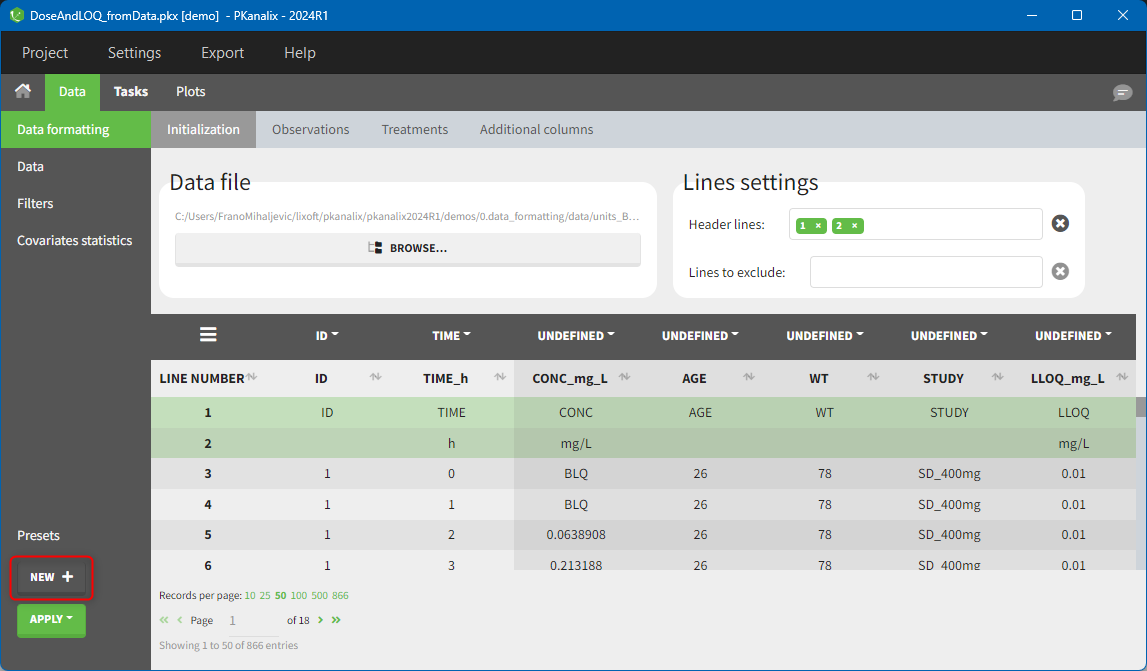

From data

The option “From data” is used to directly read censoring limits, dose amounts, administration ids, infusion durations, or rates from a dataset’s column. The column must contain either numbers or numbers inside strings. In that case, the first number found in the string is extracted (including decimals with .).

- For censoring limits, the censoring limit used to replace each censoring tag is read from the selected column on the same row.

- For doses, the value chosen for the newly created column (AMT for amount, ADMID for administration id, INFDUR for infusion duration, INFRATE for infusion rate) on each new dose line is read from the selected column on the first row found in the dataset for the same individual and the same time as the dose, or the next time if there is no line in the initial dataset at that time, or the previous time if no time is found after the dose.

Example:

- demo DoseAndLOQ_fromData.mlxtran (the screenshot below focuses on the formatting of doses and censoring and excludes other elements present in the demo):

In this demo there are three studies distinguished in the STUDY column with the categories “SD_400mg”, “SD_500mg” and “SD_600mg”. In Data Formatting, a single dose is manually defined at time 0 for all individuals, with the amount read the STUDY column. In addition, censoring interval is defined for the censoring tags BLQ, with an upper limit of the censoring interval (lower limit of quantification) read from the LLOQ_mg_L column. Three new columns – AMT for dose amounts, CENS for censoring tags (0 or 1), and LIMIT for the lower limit of the censoring intervals – are created by Data Formatting. A new dose line is then inserted at time 0 for each individual, with amount 400, 500 or 600 for studies SD_400mg, SD_500mg and SD_600mg respectively.

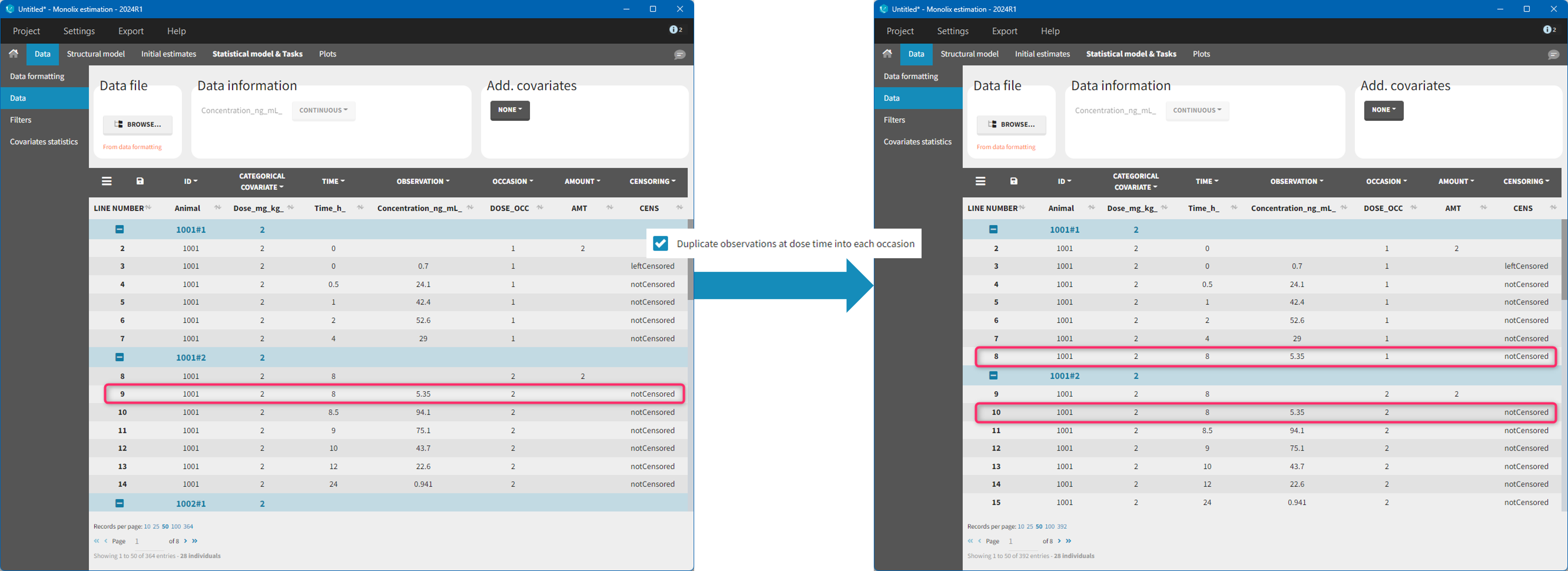

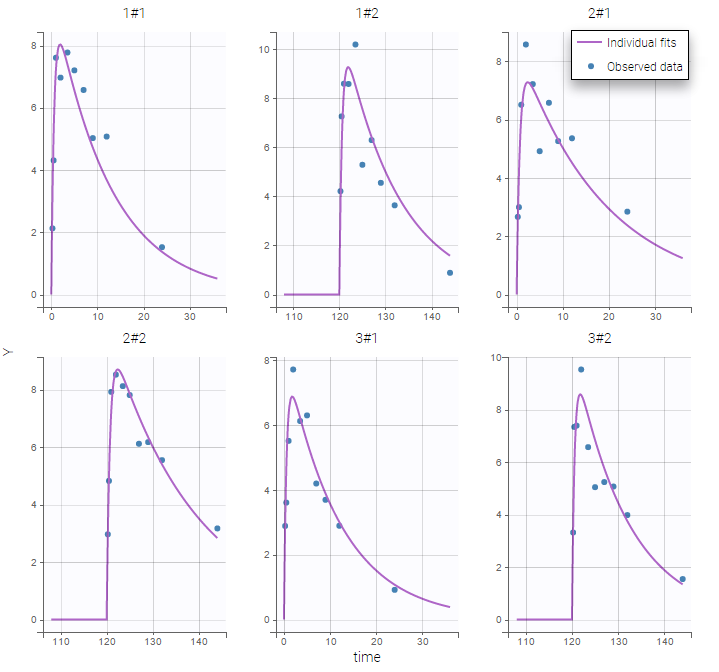

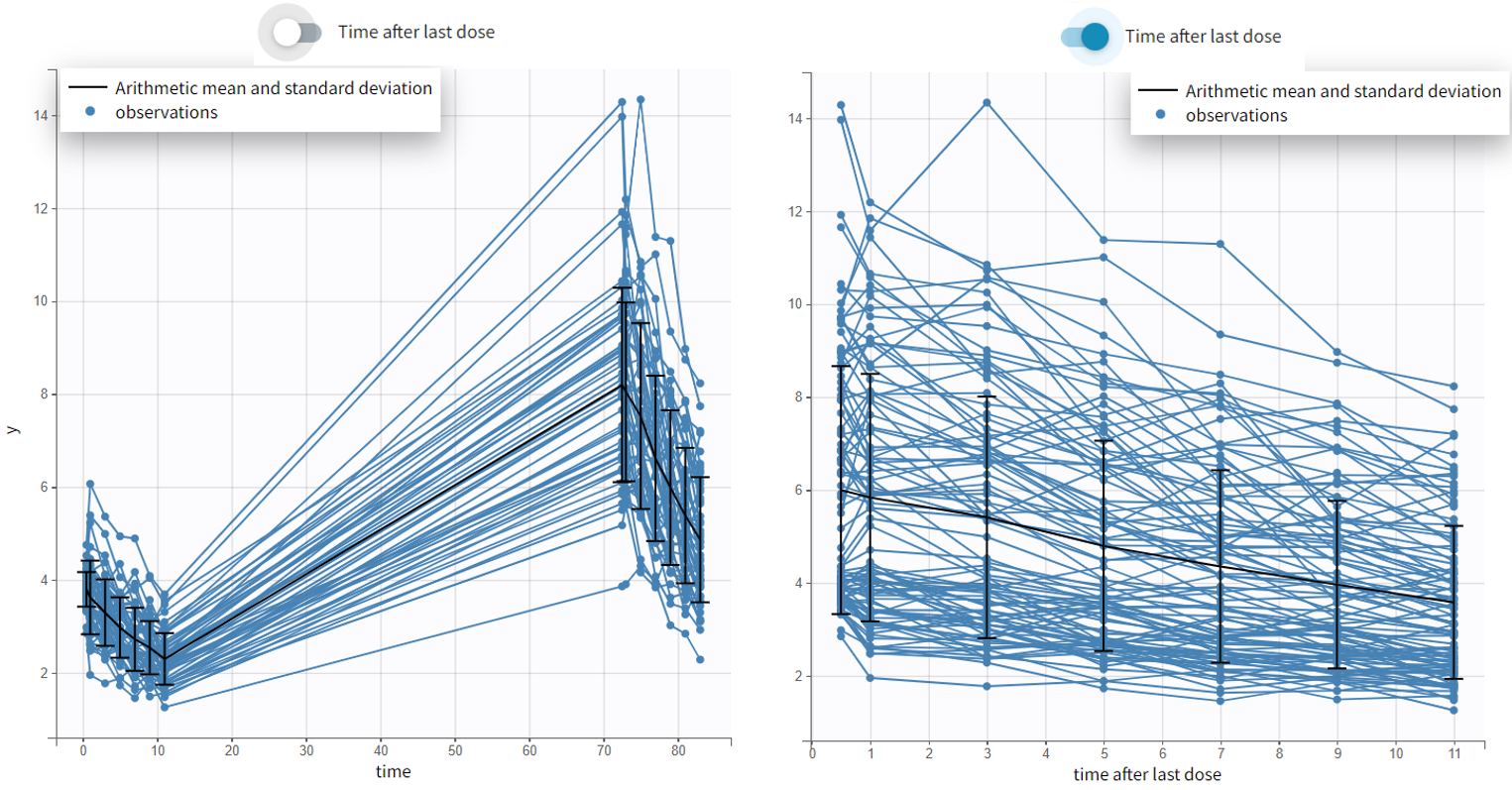

9. Creating occasions from dosing intervals

The option “Dose intervals as occasions” in the Treatments subtab of Data Formatting allows to create an occasion column to distinguish dose intervals. This is useful if the sets of measurements following different doses should be analyzed independently for a same individual. From the 2024 version on, an additional option “Duplicate observations at dose times into each occasion” is available. This option allows to duplicate the observations which are at exactly the same time as dose, such that they appear both as last point of the previous occasion and first point of the next occasion. This setting is recommended for NCA, but not recommended for population PK modeling.

Example:

- demo doseIntervals_as_Occ.mlxtran (Monolix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix):

This demo imported from a Monolix demo has an initial dataset in Monolix-standard format, with multiple doses encoded as dose lines with dose amounts in the AMT column. When using this dataset directly into Monolix or Monolix, a single analysis is done on each individual concentration profile considering all doses, which means that NCA would be done on the concentrations after the last dose only, and modeling (CA in Monolix or population modeling in Monolix) would be estimated with a single set of parameter values for each individual. If instead we want to run separate analyses on the sets of concentrations following each dose, we need to distinguish them as occasions with a new column added with the Data Formatting module. To this end, we define the same treatment as in the initial dataset with Data Formatting (here as regular multiple doses) with the option “Dose intervals as occasions” selected. After clicking Preview, Data Formatting adds two new columns: an AMT1 column with the new doses, to be tagged as AMOUNT instead of the AMT column that will now be ignored, and a DOSE_OCC column to be tagged as OCCASION.

Example:

- demo CreateOcc_duplicateObs.pkx imported to Monolix:

10. Handling urine data

In Monolix-standard format, the start and end times of urine collection intervals must be recorded in a single column, tagged as TIME column-type, where the end time of an interval automatically acts as start time for the next interval (see here for more details). If a dataset contains start and end times in two different columns, they can be merged into a single column by Data Formatting. This is done automatically by tagging these two columns as START and END in the Initialization subtab of Data Formatting (see Section 2). In addition the column containing urine collection volume must be tagged as VOLUME.

Example:

- demo Urine_LOQinObs.pkx (Monolix demo here imported into Monolix):

11. Adding new columns from an external file

The last subtab is used to insert additional columns in the dataset from a separate file. The external file must contain a table with a column named ID or id with the same subject identifiers as in the dataset to format, and other columns with a header name and individual values (numbers or strings). There can be only one value per individual, which means that the additional columns inserted in the formatted dataset can contain only a constant value within each individual, and not time-varying values.

Examples of additional columns that can be added with this option are:

- individual parameters estimated in a previous analysis, to be read as regressors to avoid estimating them. Time-varying regressors are not handled.

- new covariates.

If occasions are defined in the formatted dataset, it is possible to have an occasion column in the external file and values defined per subject-occasion.

Example:

- demo warfarin_PKPDseq_project.mlxtran (Monolix demo in the folder 0.data_formatting, here imported into Monolix):

This demo imported from a Monolix demo has an initial PKPD dataset in Monolix-standard format. The option “Additional columns” is used to add the PK parameters estimated on the PK part of the data in another Monolix project.

2.3.1.Data formatting presets

- Data formatting steps are performed on a specific project.

- Steps are saved in a data formatting preset.

- Preset is reapplied on multiple new projects (manually or automatically).

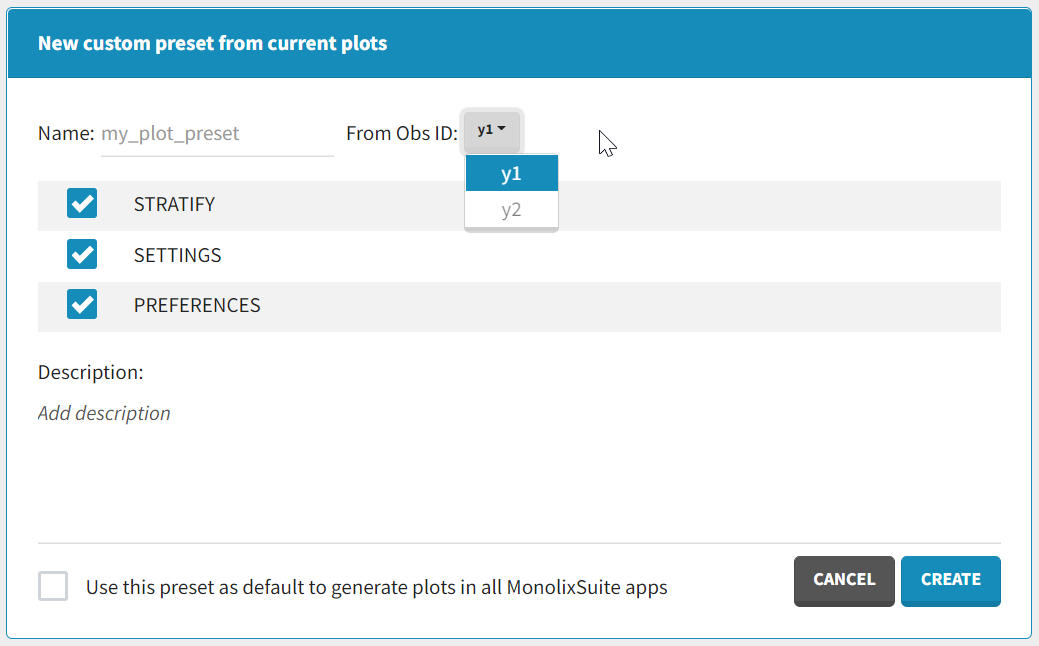

Creating a data formatting preset

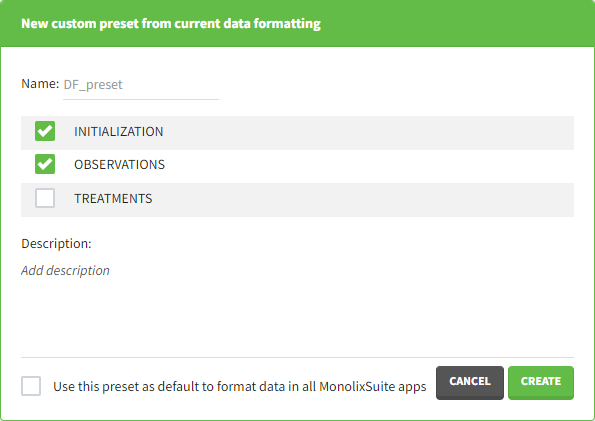

After data formatting steps are done on a project, a preset can be created by clicking on the New button in the bottom left corner of the interface, while in the Data formatting tab:

- Name: contains a name of the preset, this information will be used to distinguish between presets when applying them.

- Configuration: contains three checkboxes (initialization, observations, treatments). Users can choose which steps of data formatting will be saved in the preset. If option “External” was used in creating treatments, the external file paths will not be saved in the preset.

- Description: a custom description can be added.

- Use this preset as default to format data in all MonolixSuite apps: if ticked, the preset will be automatically applied every time a data set is loaded for data formatting in PKanalix and Monolix.

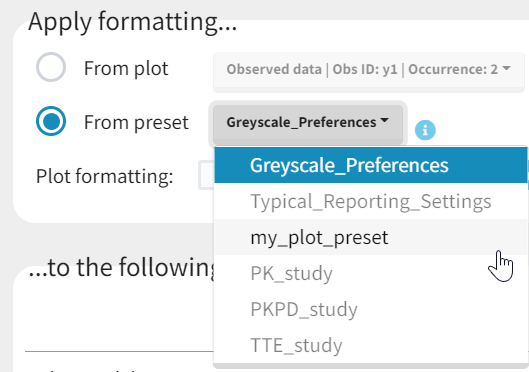

Applying a preset

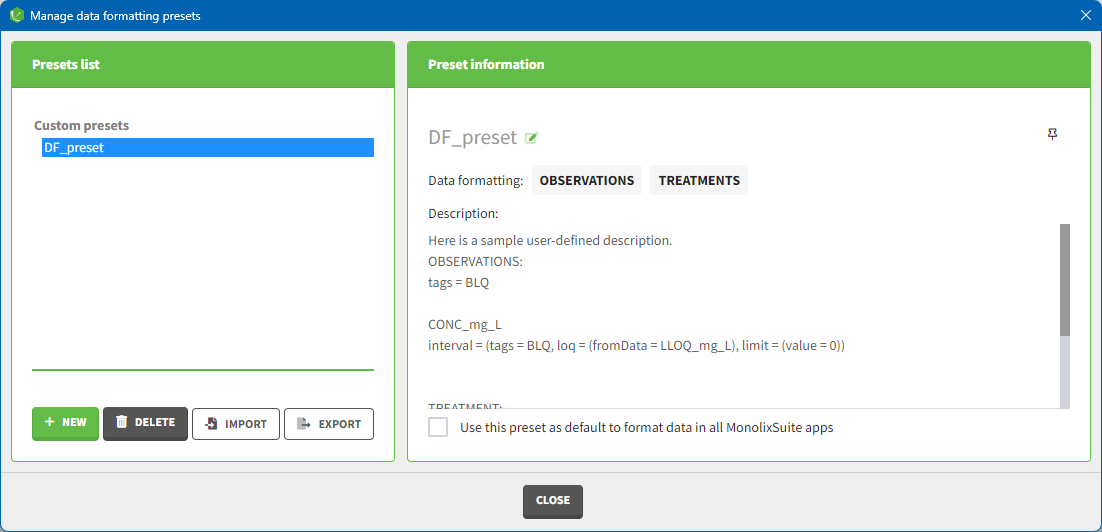

A preset can be applied manually using the Apply button in the bottom left corner of the data formatting tab. Clicking on the Apply button will open a dropdown selection of all saved presets and the desired preset can be chosen. The Apply button is enabled only after the initialization step is performed (ID and TIME columns are selected and the button Next was clicked). This allows PKanalix to fall back to the initialized state, if the initialization step from a preset fails (e.g., if ID and TIME column header saved in the presets do not exist in the new data set). After applying a preset, all data formatting steps saved in the preset will try to be applied. If it is not possible to apply certain steps (e.g., some censoring tags or column headers saved in a preset do not exist), the error message will appear.Managing presets

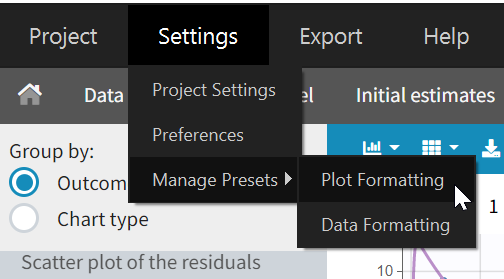

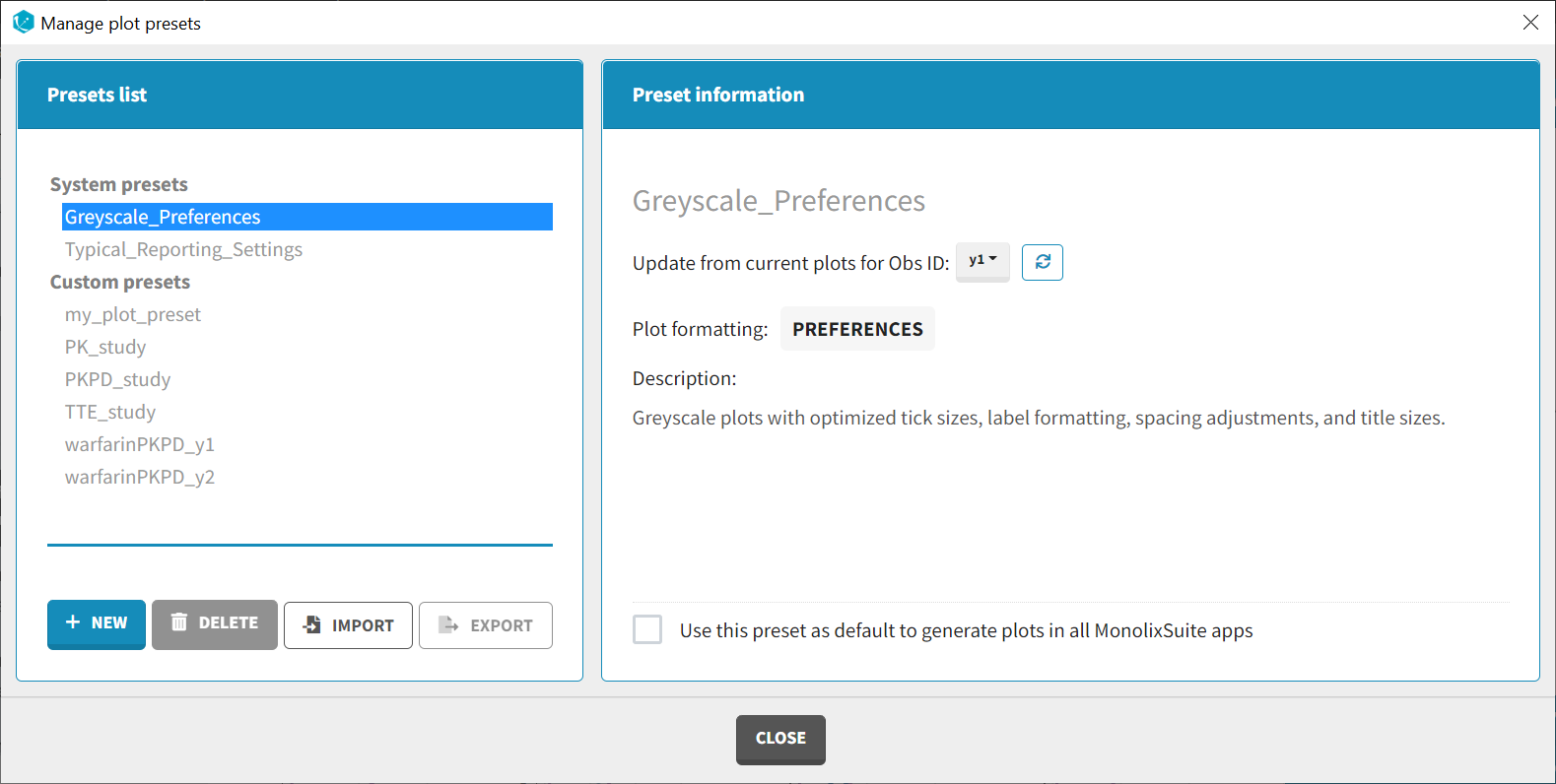

Presets can be created, deleted, edited, imported and exported by clicking on Settings > Manage Presets > Data Formatting.

- Create presets: clicking on the button New has the same behavior as clicking on the button New in the Data formatting tab (described in the section “Creating a data formatting preset”).

- Delete presets: clicking on the button Delete will permanently delete a preset. Clicking on this button will not ask for confirmation.

- Edit presets: by clicking on a preset in the left panel, the preset information will appear in the right panel. Name and preset description of the presets can then be updated, and a preset can be selected to automatically format data in PKanalix and Monolix.

- Export presets: a selected preset can be exported as a lixpst file which can be shared between users and imported using the Import button.

- Import presets: a user can import a preset from a lixpst file exported from another computer.

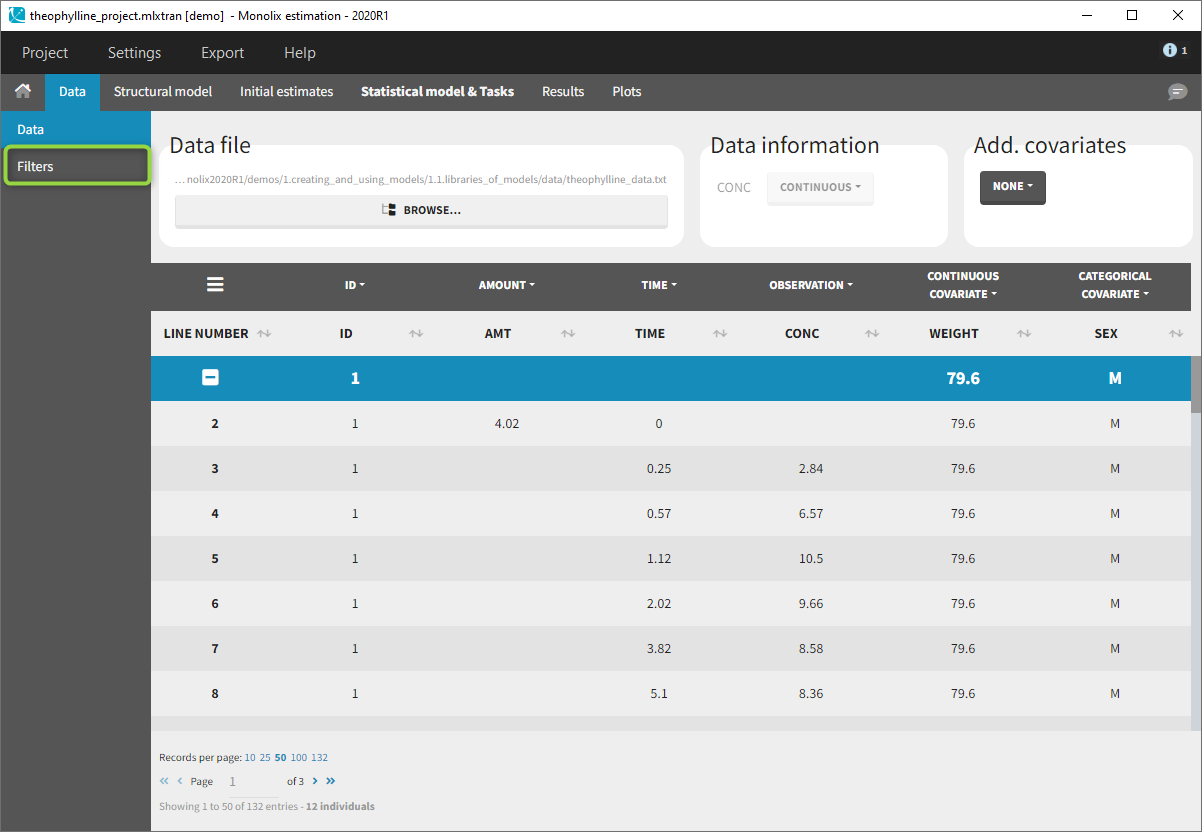

2.4.Filtering a data set

Starting on the 2020 version, it is possible to filter your data set to only take a subpart into account in your modelization. It allows to make filters on some specific IDs, times, measurement values,… It is also possible to define complementary filters and also filters of filters. It is accessible through the filters item on the data tab.

- Creation of a filter

- Filtering actions

- Filters with several actions

- Other filers: filter of filter and complementary filters

Creation of a filter

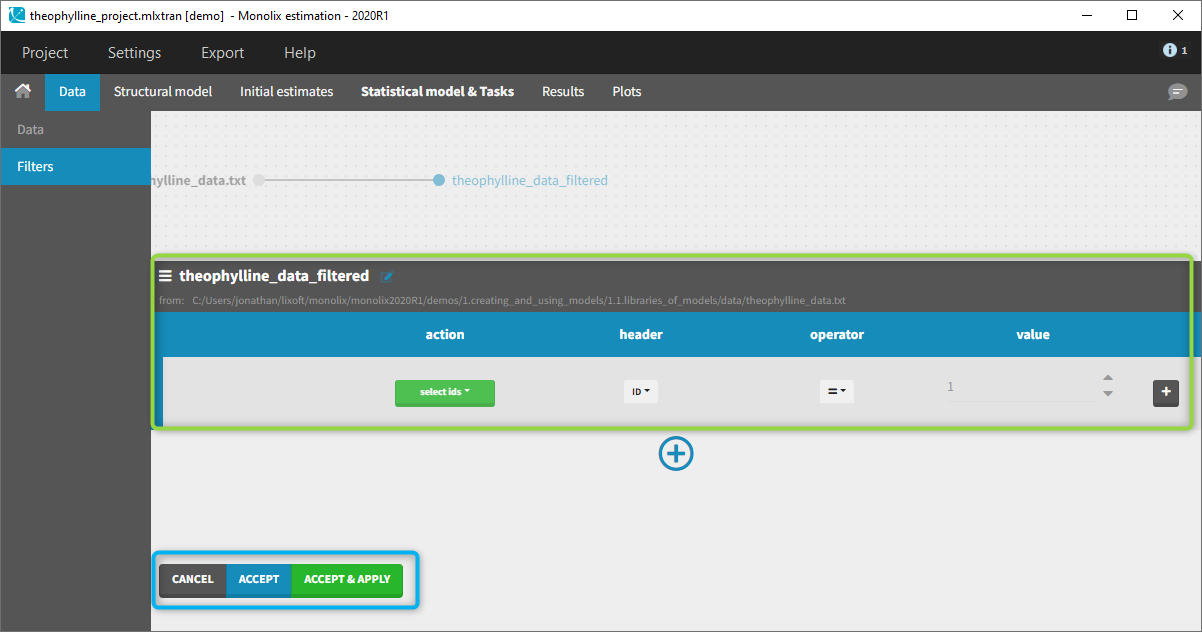

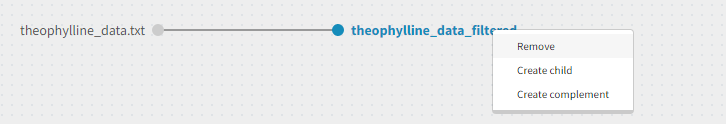

To create a filter, you need to click on the data set name. You can then create a “child”. It corresponds to a subpart of the data set where you will define your filtering actions.

You can see on the top (in the green rectangle) the action that you will complete and you can CANCEL, ACCEPT, or ACCEPT & APPLY with the bottoms on the bottom.

Filtering actions

In all the filtering actions, you need to define

- An action: it corresponds to one of the following possibilities: select ids, remove ids, select lines, remove lines.

- A header: it corresponds to the column of the data set you wish to have an action on. Notice that it corresponds to a column of the data set that was tagged with a header.

- An operator: it corresponds to the operator of choice (=, ≠, < ≤, >, or ≥).

- A value. When the header contains numerical values, the user can define it. When the header contains strings, a list is proposed.

For example, you can

- Remove the ID 1 from your study:

In that case, all the IDs except ID = 1 will be used for the study. - Select all the lines where the time is less or equal 24:

In that case, all lines with time strictly greater that 24 will be removed. If a subject has no measurement anymore, it will be removed from the study. - Select all the ids where SEX equals F:

In that case, all the male will be removed of the study. - Remove all Ids where WEIGHT less or equal 65:

In that case, only the subjects with a weight over 65 will be kept for the study.

In any case, the interpreted filter data set will be displayed in the data tab.

Filters with several actions

In the previous examples, we only did one action. It is also possible to do several actions to define a filter. We have the possibility to define UNION and/or INTERSECTION of actions.

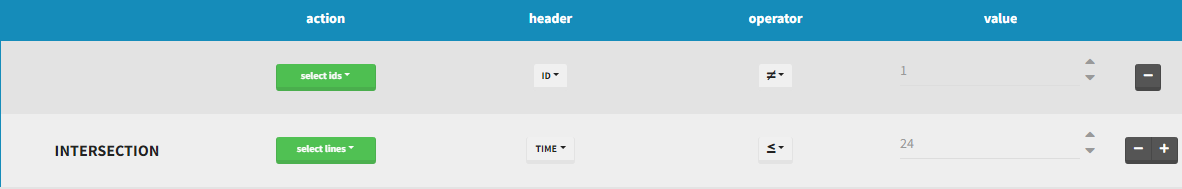

INTERSECTION

By clicking by the + and – button on the right, you can define an intersection of actions. For example, by clicking on the +, you can define a filter corresponding to intersection of

- The IDs that are different to 1.

- The lines with the time values less than 24.

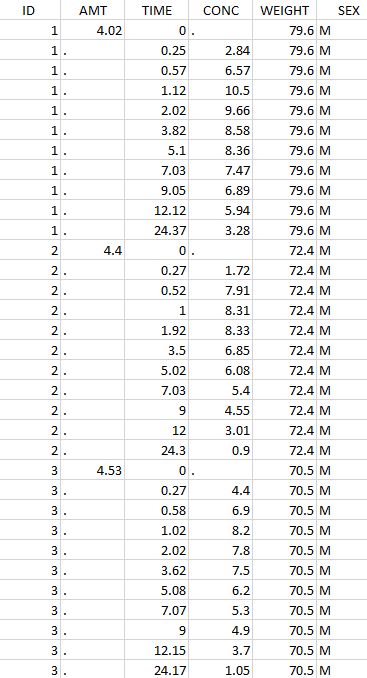

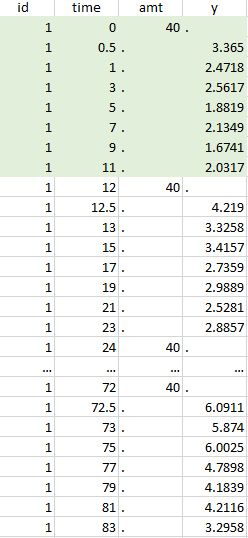

Thus in that case, all the lines with a time less than 24 and corresponding to an ID different than 1 will be used in the study. If we look at the following data set as an example

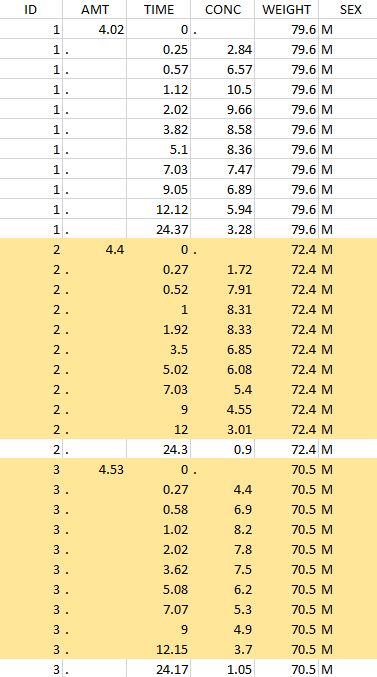

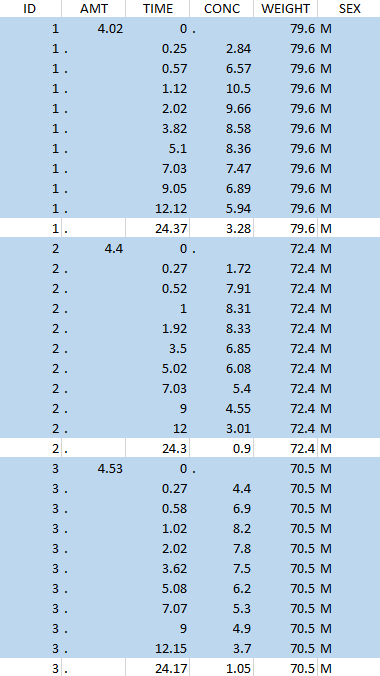

Initial data set |

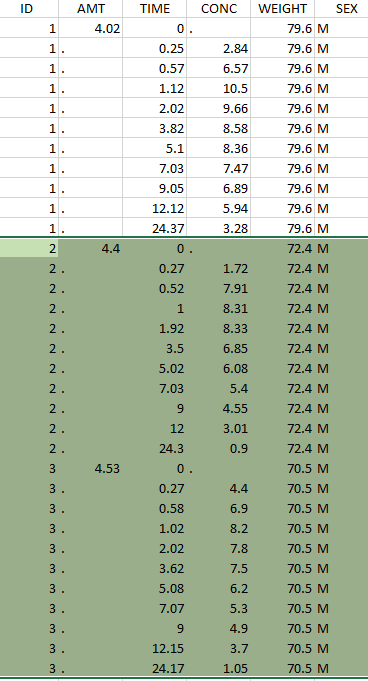

Resulting data set after action: select IDs ≠ 1 Resulting data set after action: select IDs ≠ 1 |

Considered data set for the study as the intersection of the two actions |

Resulting data set after action: select lines with time ≤ 24 Resulting data set after action: select lines with time ≤ 24 |

UNION

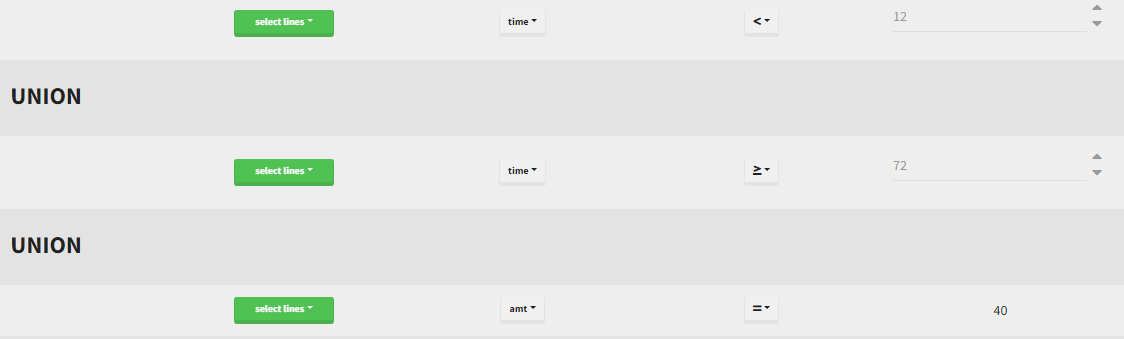

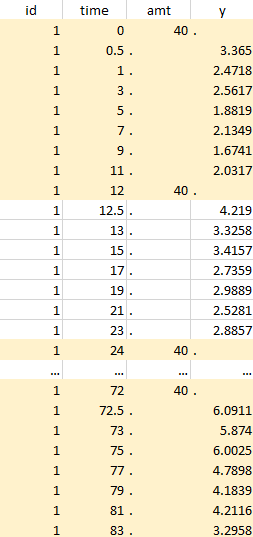

By clicking by the + and – button on the bottom, you can define an union of actions. For example, in a data set with a multi dose, I can focus on the first and the last dose. Thus, by clicking on the +, you can define a filter corresponding to union of

- The lines where the time is strictly less than 12.

- The lines where the time is greater than 72.

Initial data set |

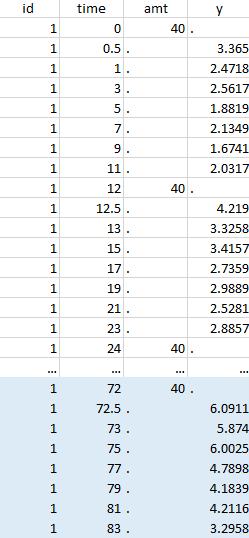

Resulting data set after action: select lines where the time is strictly less than 12 |

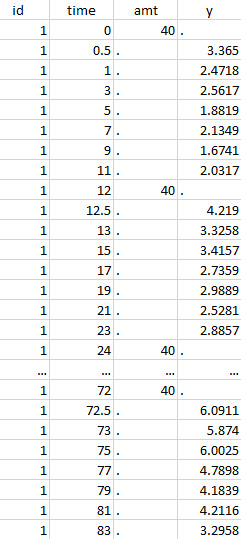

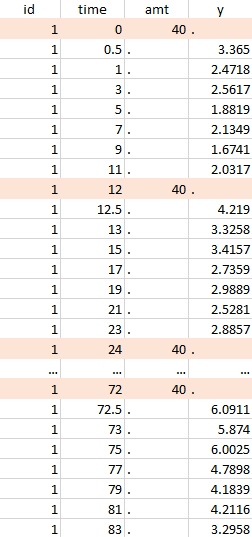

Considered data set for the study as the union of the three actions |

Resulting data set after action: select lines where the time is greater than 72 |

||

Resulting data set after action: select lines where amt equals 40 |

Notice that, if just define the first two actions, all the dose lines at a time in ]12, 72[ will also be removed. Thus, to keep having all the doses, we need to add the condition of selecting the lines where the dose is defined.

In addition, it is possible to do any combination of INTERSECTION and UNION.

Other filers: filter of filter and complementary filters

Based on the definition of a filter, it is possible to define two other actions. By clicking on the filter, it is possible to create

- A child: it corresponds to a new filter with the initial filter as the source data set.

- A complement: corresponds to the complement of the filter. For example, if you defined a filter with only the IDs where the SEX is F, then the complement corresponds to the IDs where the SEX is not F.

2.5.Handling censored (BLQ) data

- Introduction

- Theory

- Censoring definition in a data set

- PK data below a lower limit of quantification

- PK data below a lower limit of quantification or below a limit of detection

- PK data below a lower limit of quantification and PD data above an upper limit of quantification

- Combination of interval censored PK and PD data

- Case studies

Objectives: learn how to handle easily and properly censored data, i.e. data below (resp. above) a lower (resp.upper) limit of quantification (LOQ) or below a limit of detection (LOD).

Projects: censoring1log_project, censoring1_project, censoring2_project, censoring3_project, censoring4_project

Introduction

Censoring occurs when the value of a measurement or observation is only partially known. For continuous data measurements in the longitudinal context, censoring refers to the values of the measurements, not the times at which they were taken. For example, the lower limit of detection (LLOD) is the lowest quantity of a substance that can be distinguished from its absence. Therefore, any time the quantity is below the LLOD, the “observation” is not a measurement but the information that the measured quantity is less than the LLOD. Similarly, in longitudinal studies of viral kinetics, measurements of the viral load below a certain limit, referred to as the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), are so low that their reliability is considered suspect. A measuring device can also have an upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) such that any value above this limit cannot be measured and reported.

As hinted above, censored values are not typically reported as a number, but their existence is known, as well as the type of censoring. Thus, the observation (i.e., what is reported) is the measurement

if not censored, and the type of censoring otherwise.

We usually distinguish between three types of censoring: left, right and interval. In each case, the SAEM algorithm implemented in Monolix properly computes the maximum likelihood estimate of the population parameters, combining all the information provided by censored and non censored data.

Theory

In the presence of censored data, the conditional density function needs to be computed carefully. To cover all three types of censoring (left, right, interval), let be the (finite or infinite) censoring interval existing for individual i at time

. Then,

$$\displaystyle p(y^{(r)}|\psi)=\prod_{i=1}^{N}\prod_{j=1}^{n_i}p(y_{ij}|\psi_i)^{1_{y_{ij}\notin I_{ij}}}\mathbb{P}(y_{ij}\in I_{ij}|\psi_i)^{1_{y_{ij}\in I_{ij}}}$$

where

$$\displaystyle \mathbb{P}(y_{ij}\in I_{ij}|\psi_i)=\int_{I_{ij}} p_{y_{ij}|\psi_i} (u|\psi_i)du$$

We see that if is not censored (i.e.

), its contribution to the likelihood is the usual

, whereas if it is censored, the contribution is

.

For the calculation of the likelihood, this is equivalent to the M3 method in NONMEM when only the CENSORING column is given, and to the M4 method when both a CENSORING column and a LIMIT column are given.

Censoring definition in a data set

In the dataset format used by Monolix and PKanalix, censored information is included in this way:

- The censored measurement should be in the OBSERVATION column.

- In an additional CENSORING column, put 0 if the observation is not censored, and 1 or – 1 depending if the measurement given in the observation column is a lower or an upper limit.

- Optionally, include a LIMIT column to set the other limit.

To quickly include censoring information to your dataset by using BLQ tags in the observation column, you can use data formatting.

Examples are provided below and here.

PK data below a lower limit of quantification

Left censored data

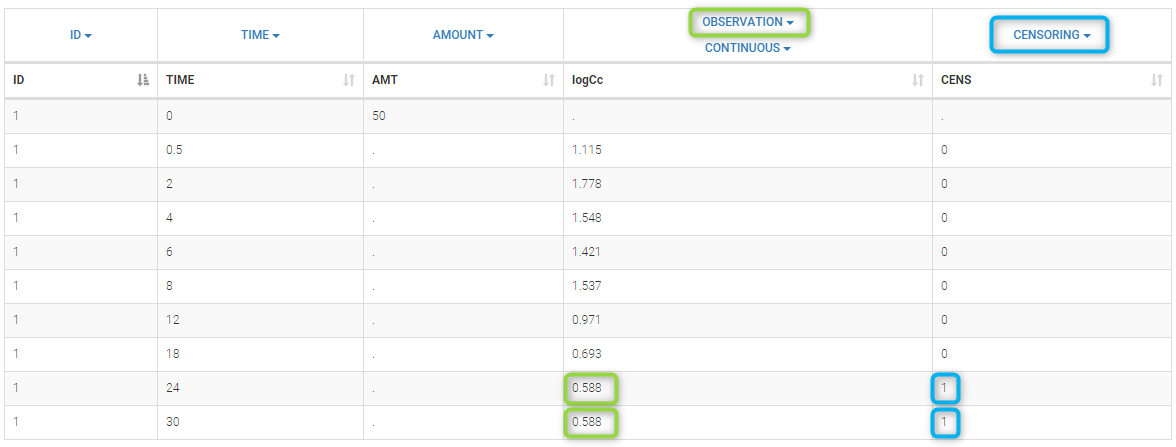

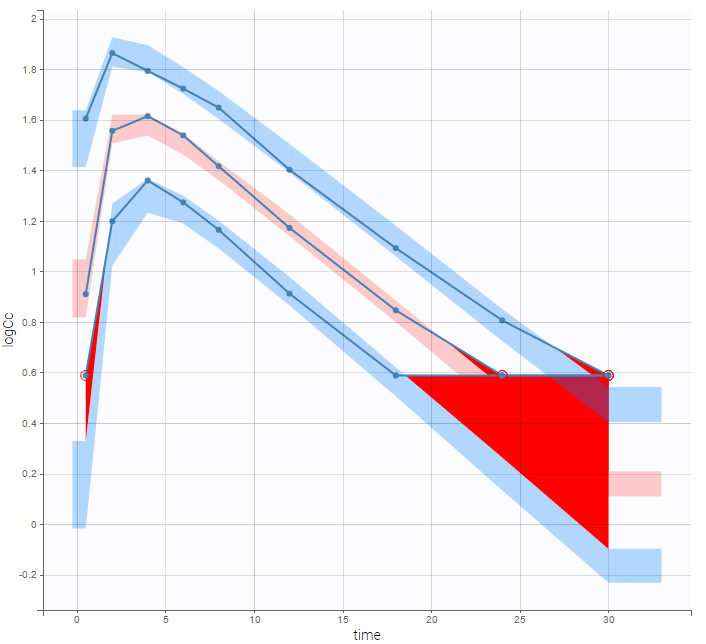

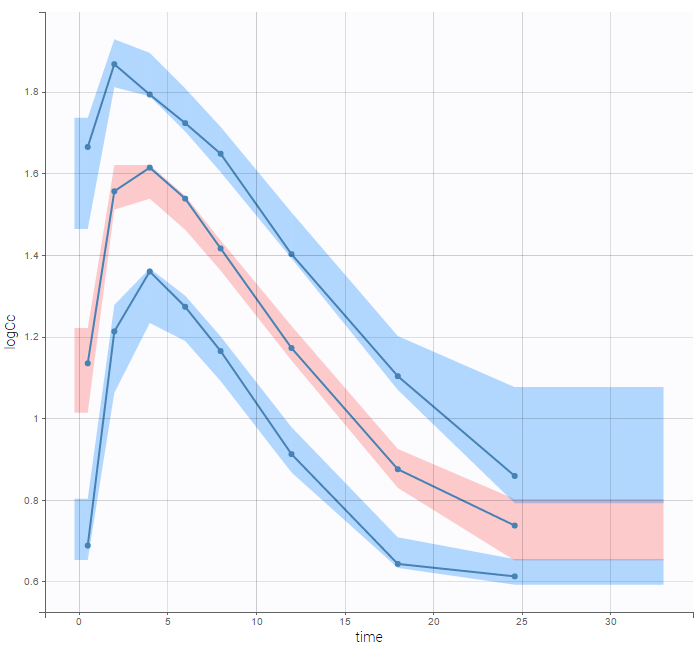

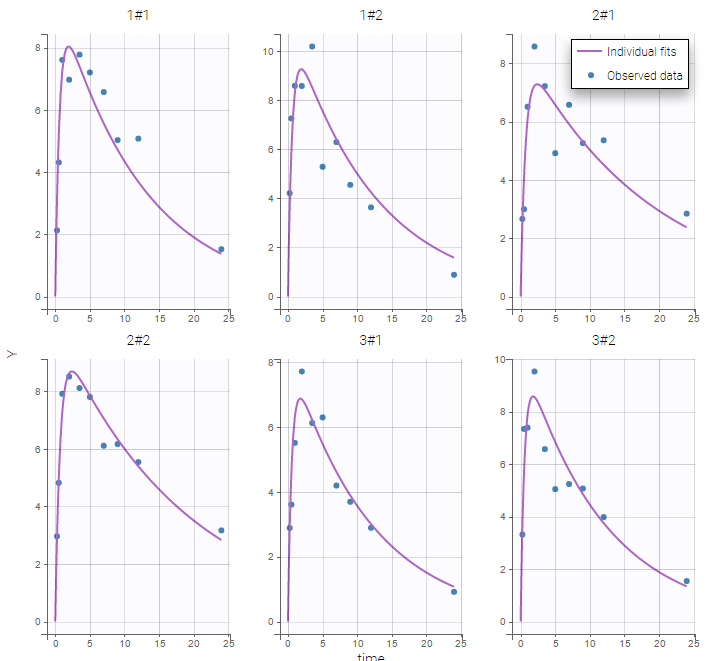

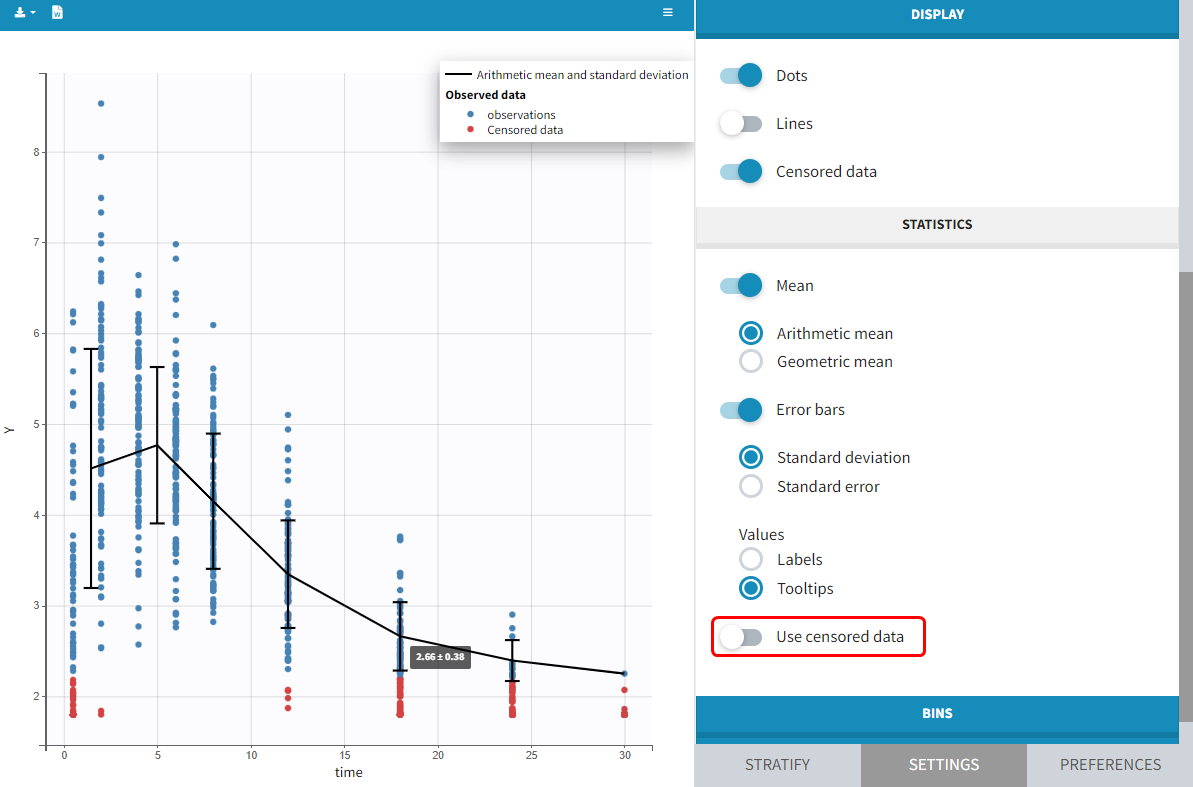

- censoring1log_project (data = ‘censored1log_data.txt’, model = ‘pklog_model.txt’)

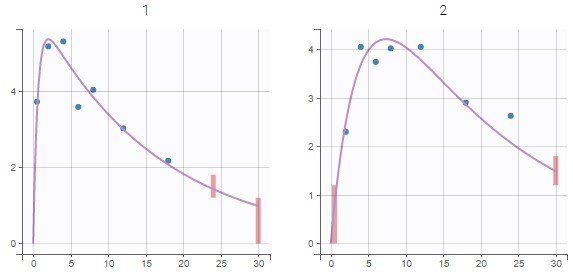

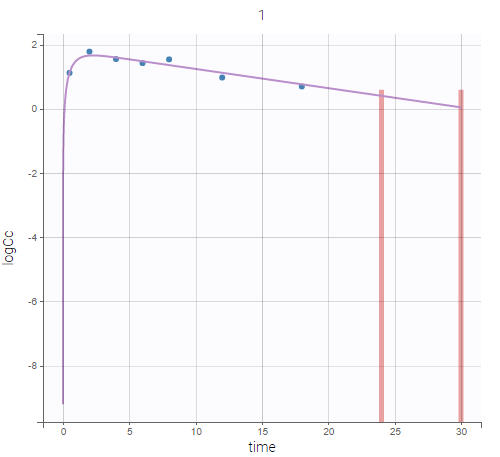

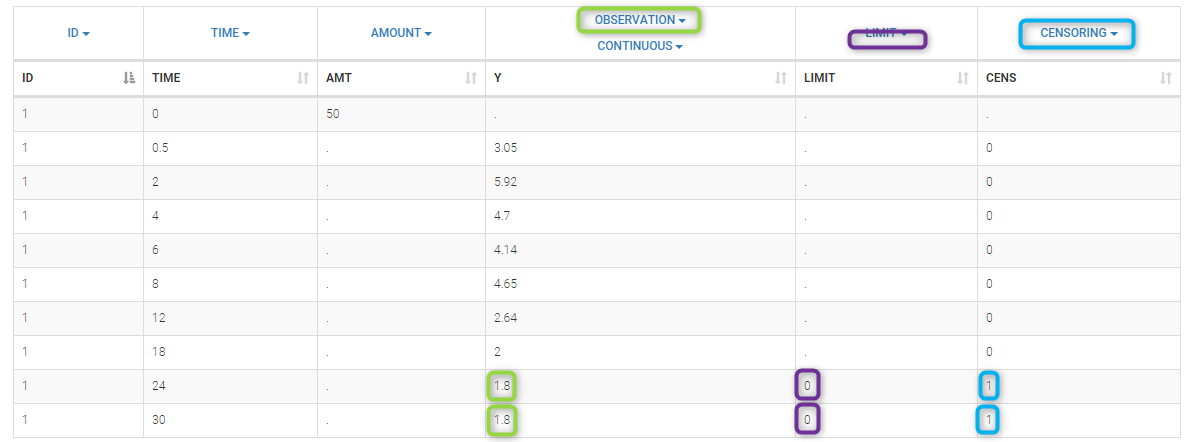

PK data are log-concentration in this example. The limit of quantification of 1.8 mg/l for concentrations becomes log(1.8)=0.588 for log-concentrations. The column of observations (Y) contains either the LLOQ for data below the limit of quantification (BLQ data) or the measured log-concentrations for non BLQ data. Furthermore, Monolix uses an additional column CENSORING to indicate if an observation is left censored (CENS=1) or not (CENS=0). In this example, subject 1 has two BLQ data at times 24h and 30h (the measured log-concentrations were below 0.588 at these times):

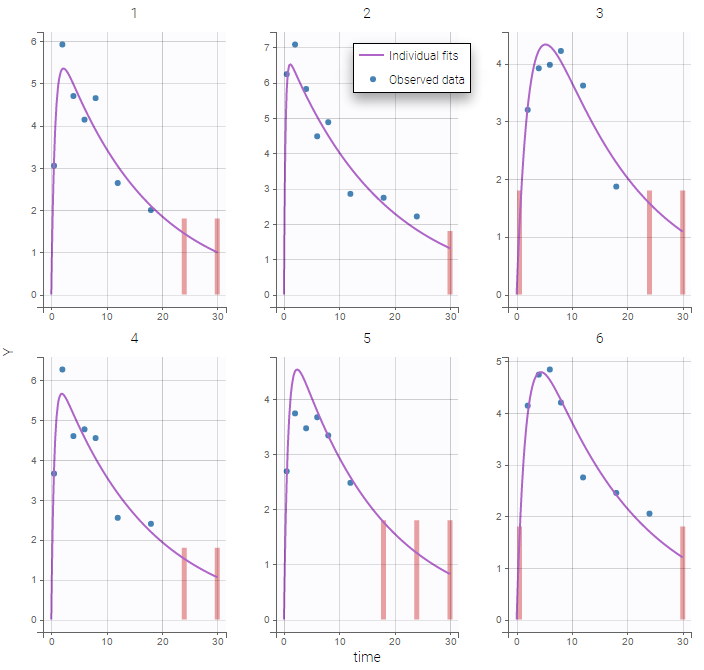

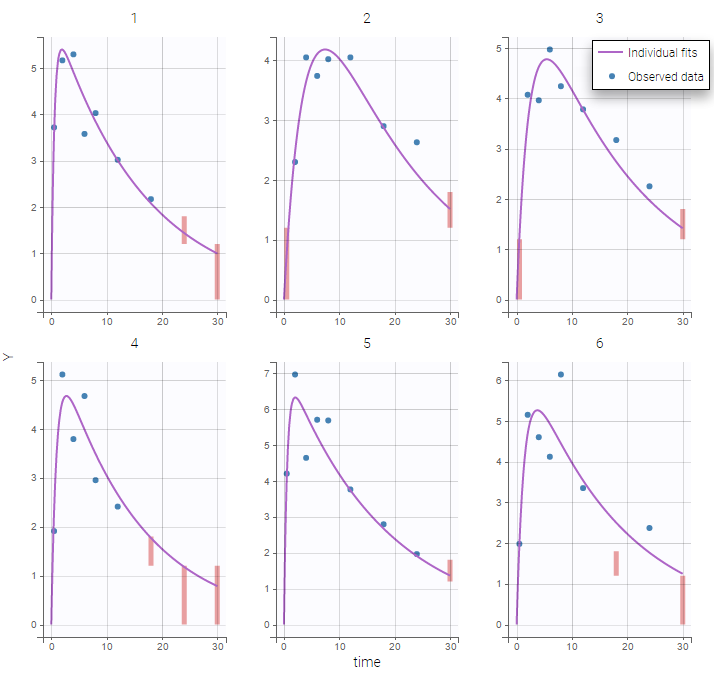

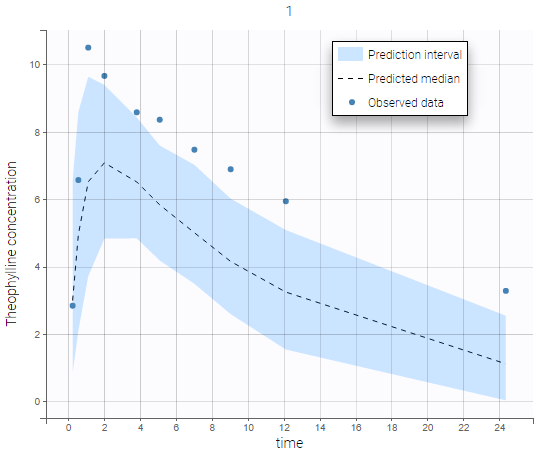

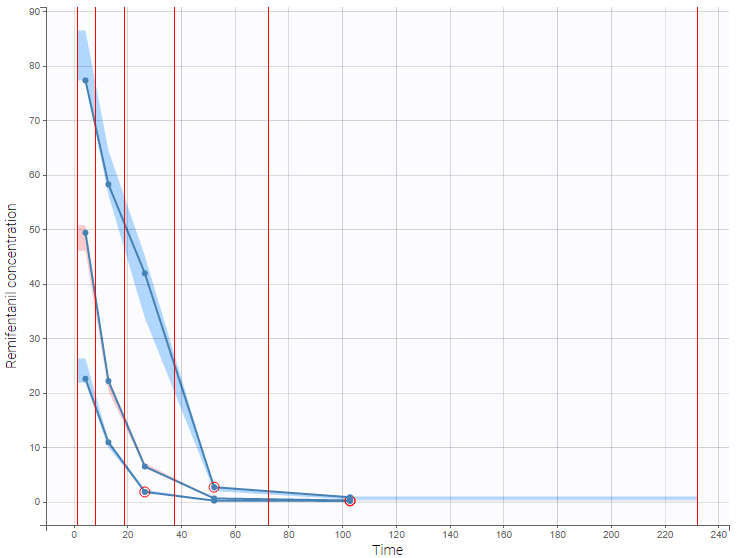

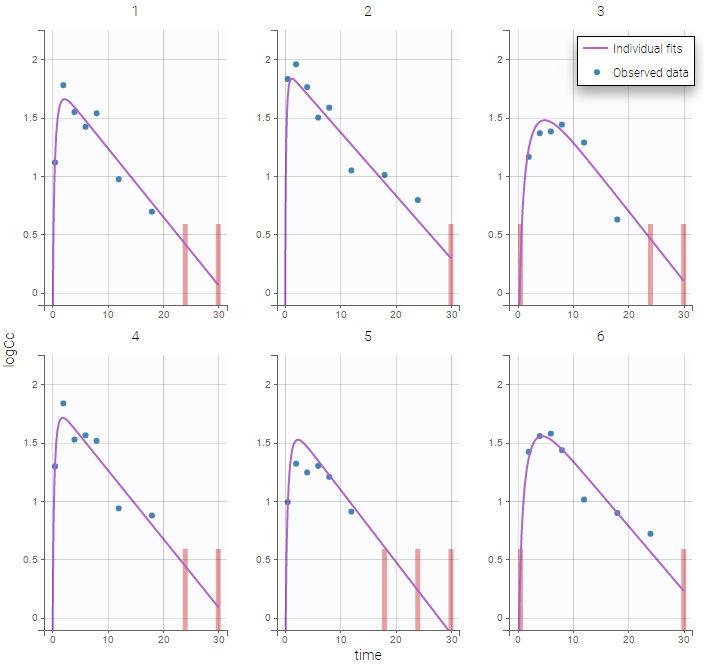

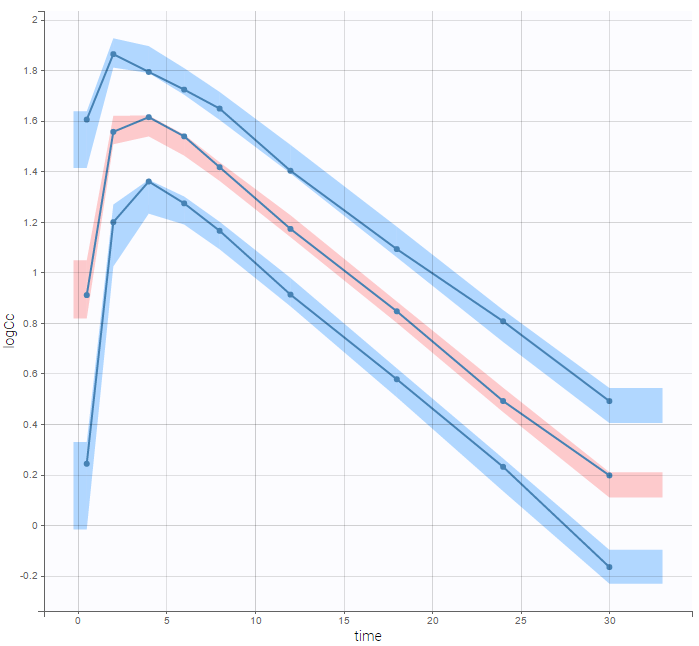

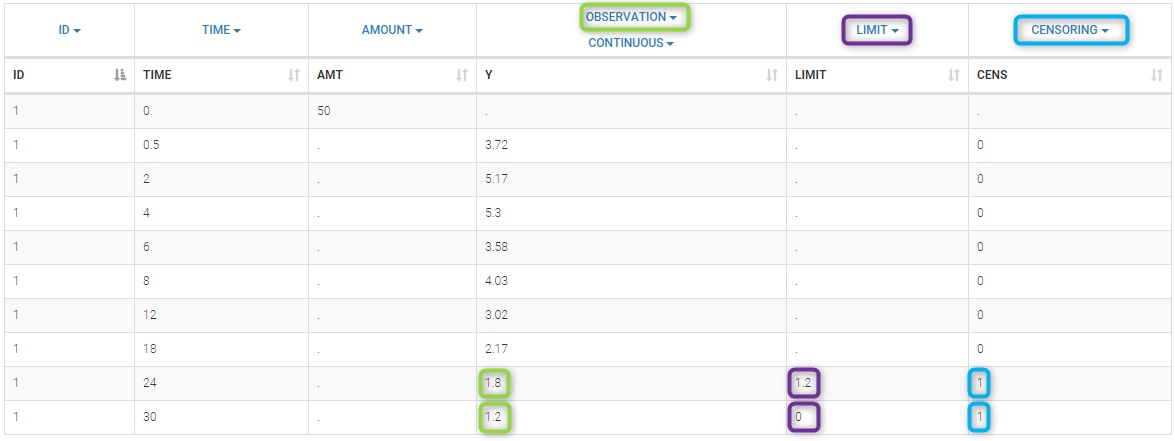

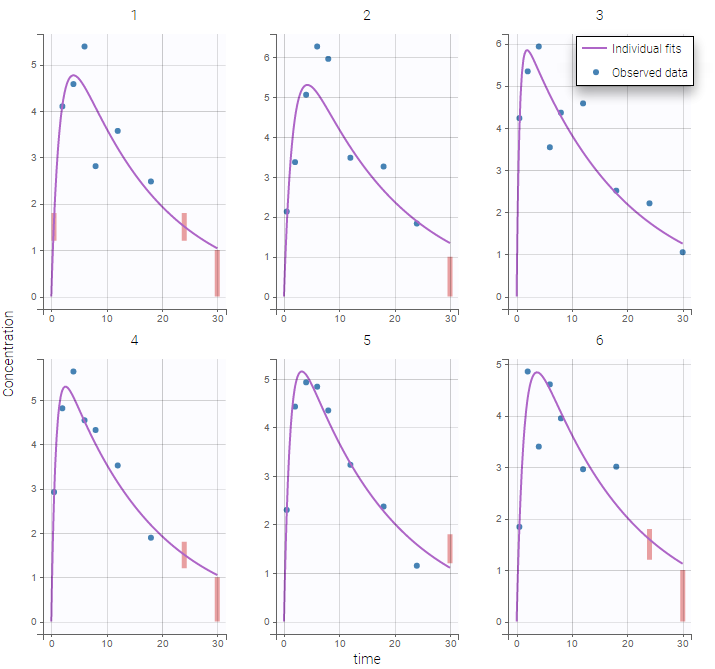

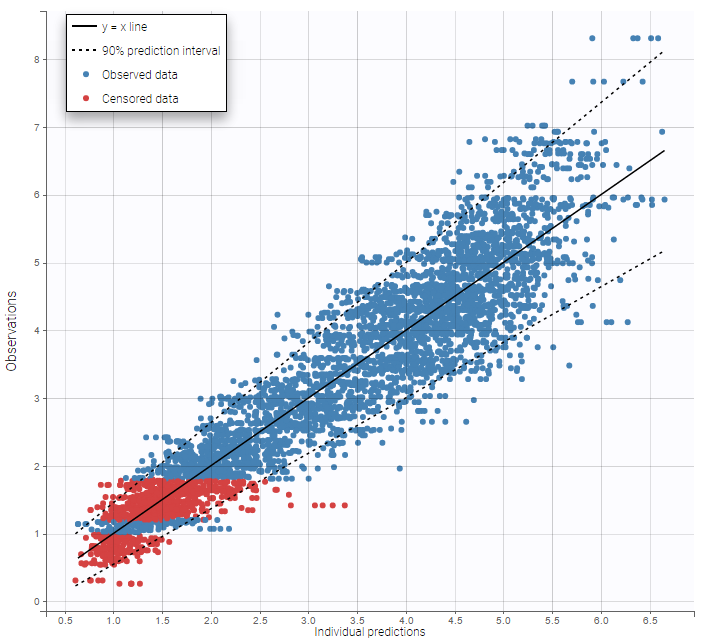

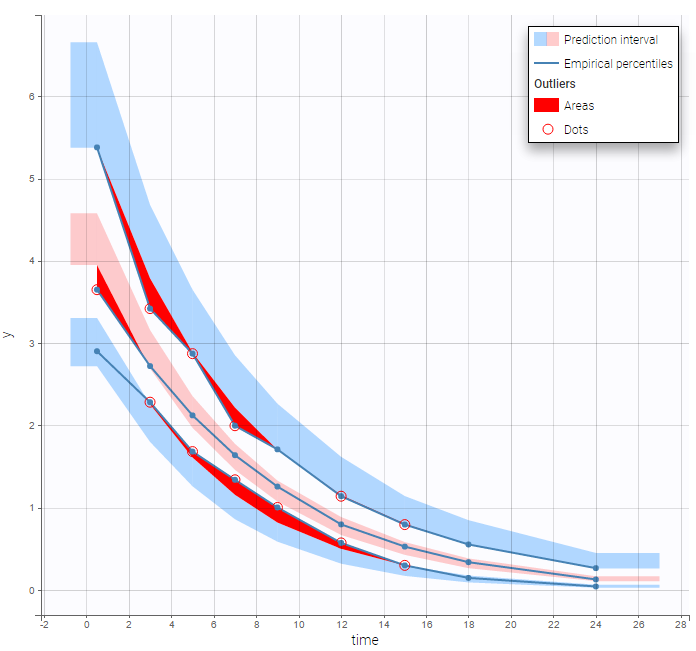

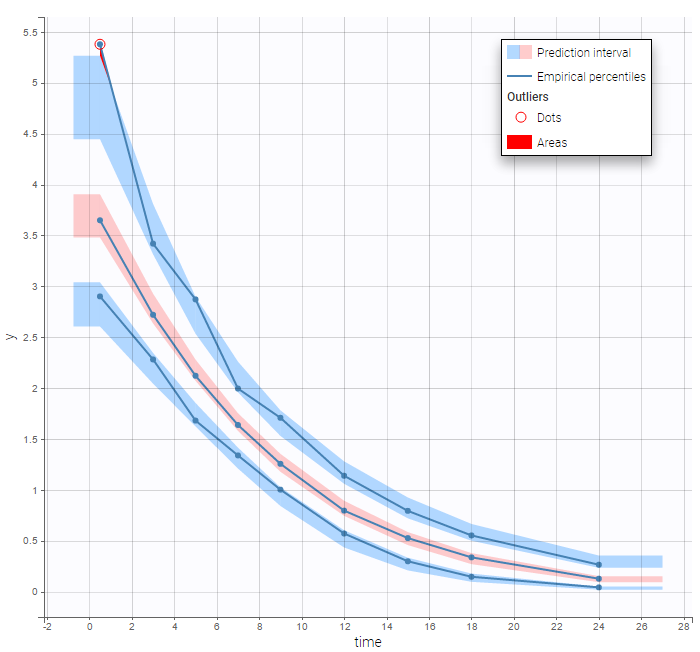

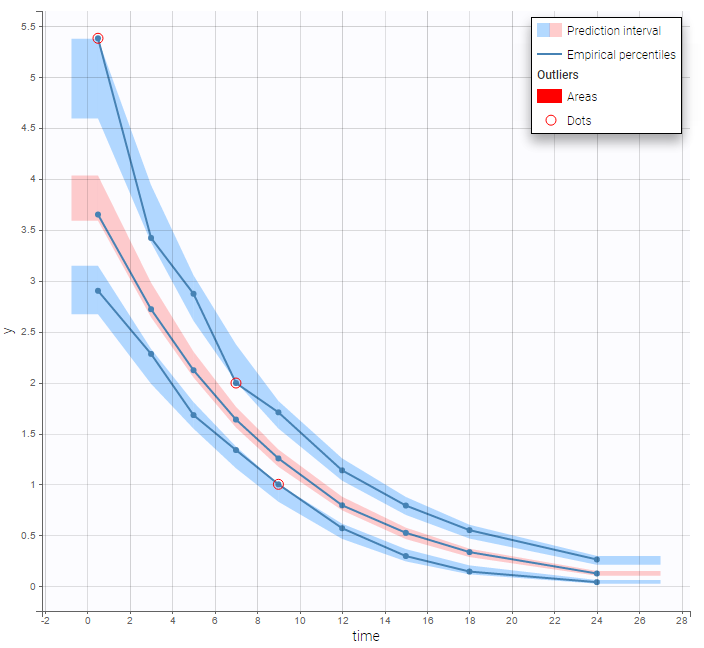

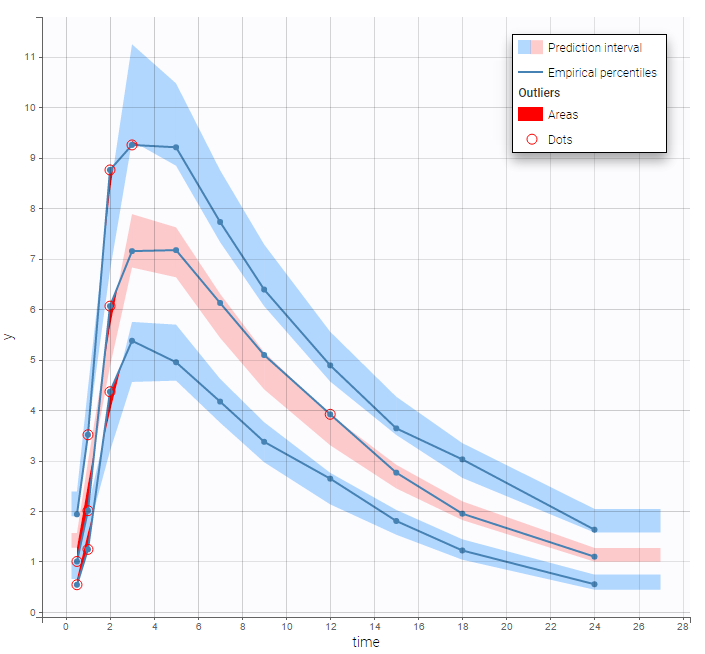

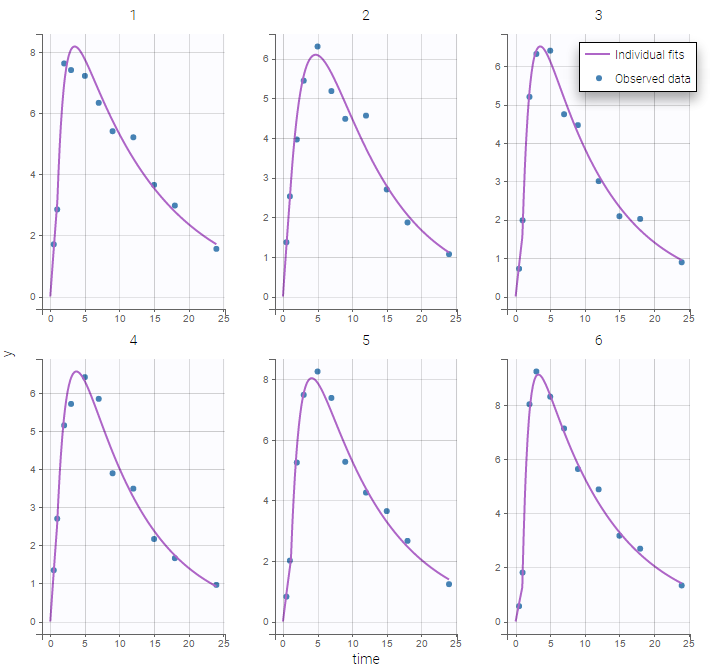

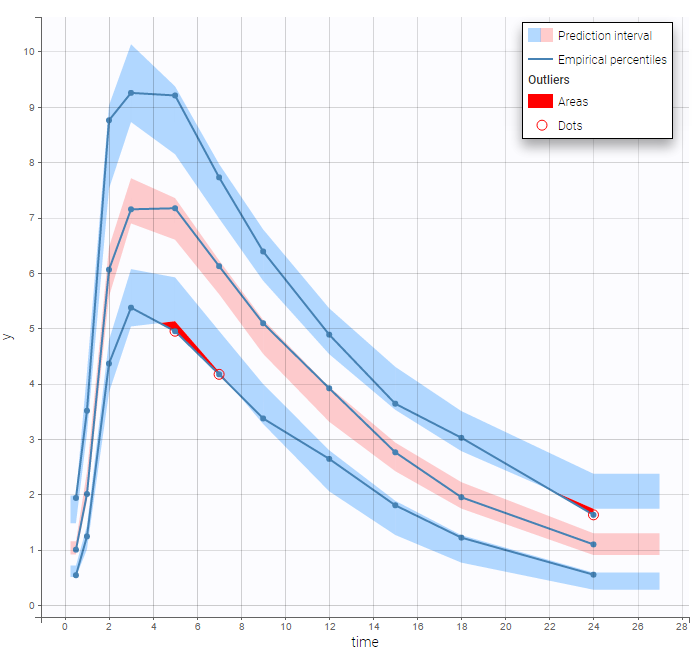

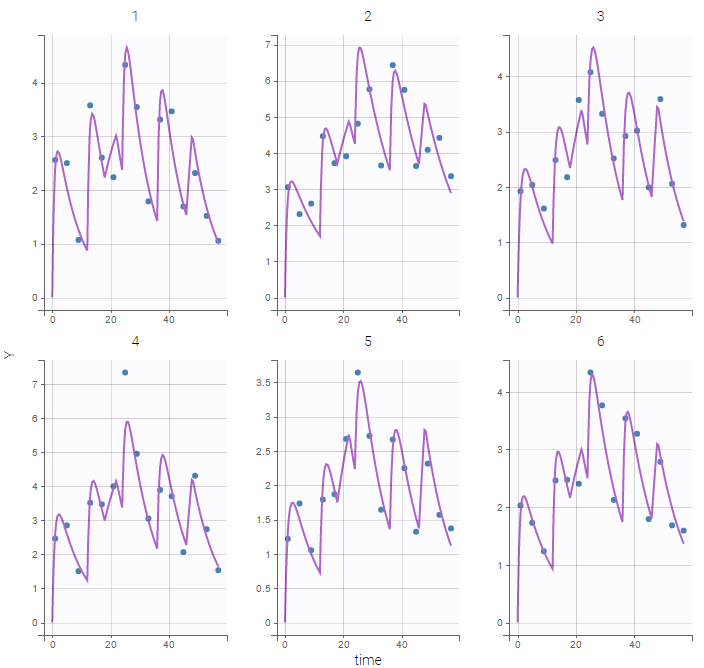

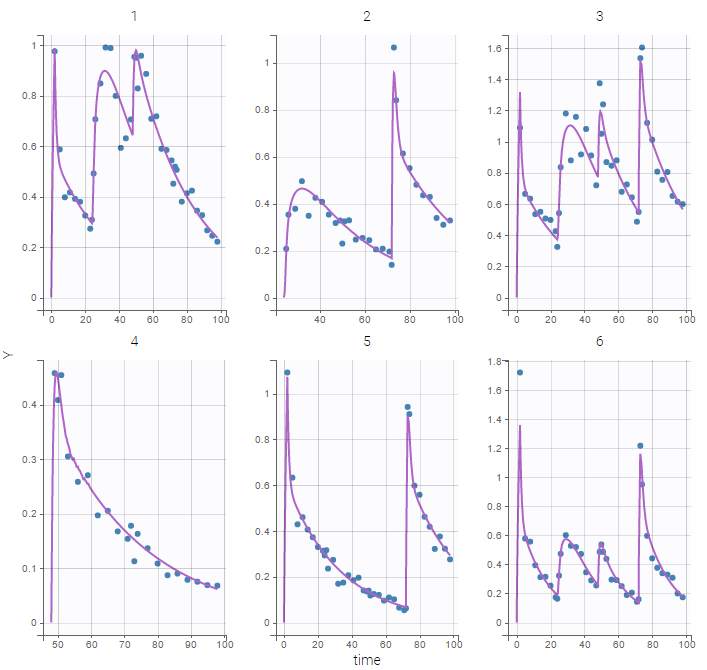

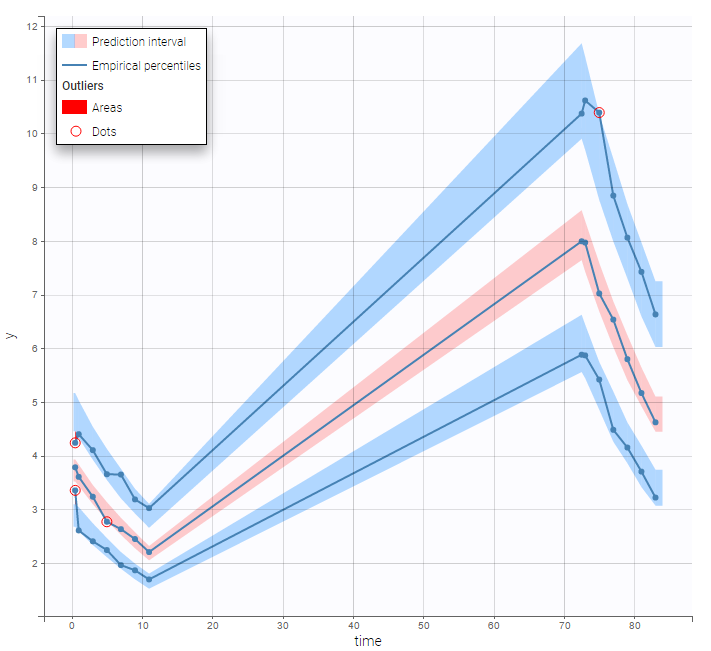

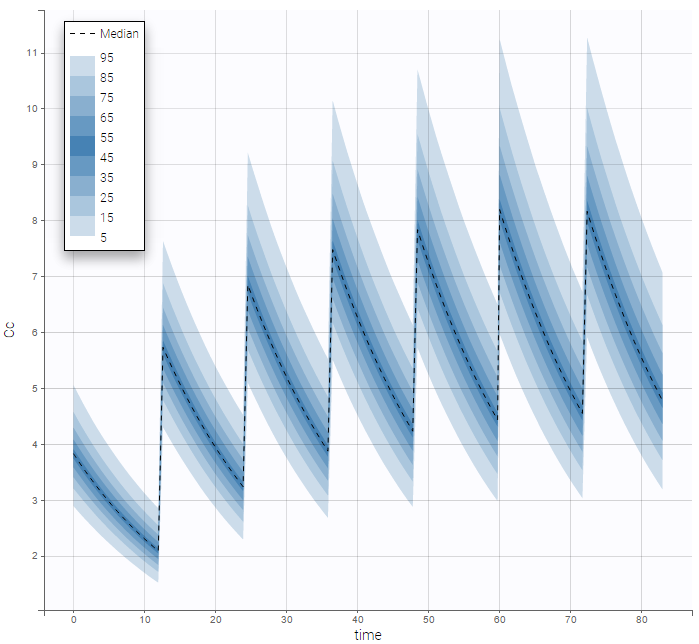

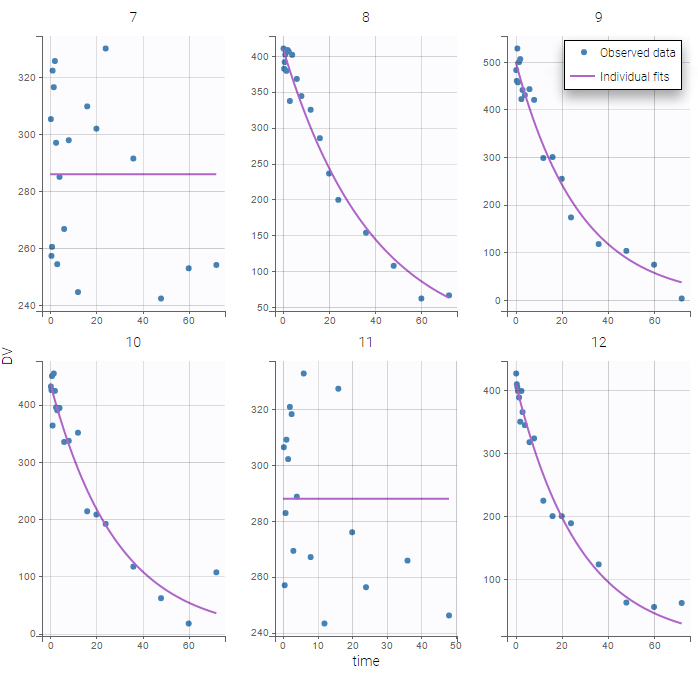

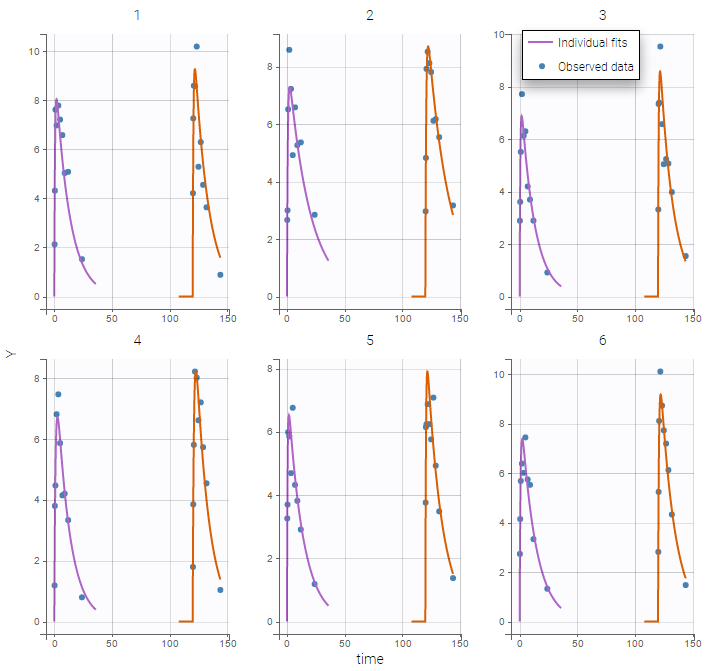

The plot of individual fits displays BLQ (red band) and non BLQ data (blue dots) together with the predicted log-concentrations (purple line) on the whole time interval:

Notice that the band goes from .8 to -Infinity as no bound has been specified (no LIMIT column was proposed).

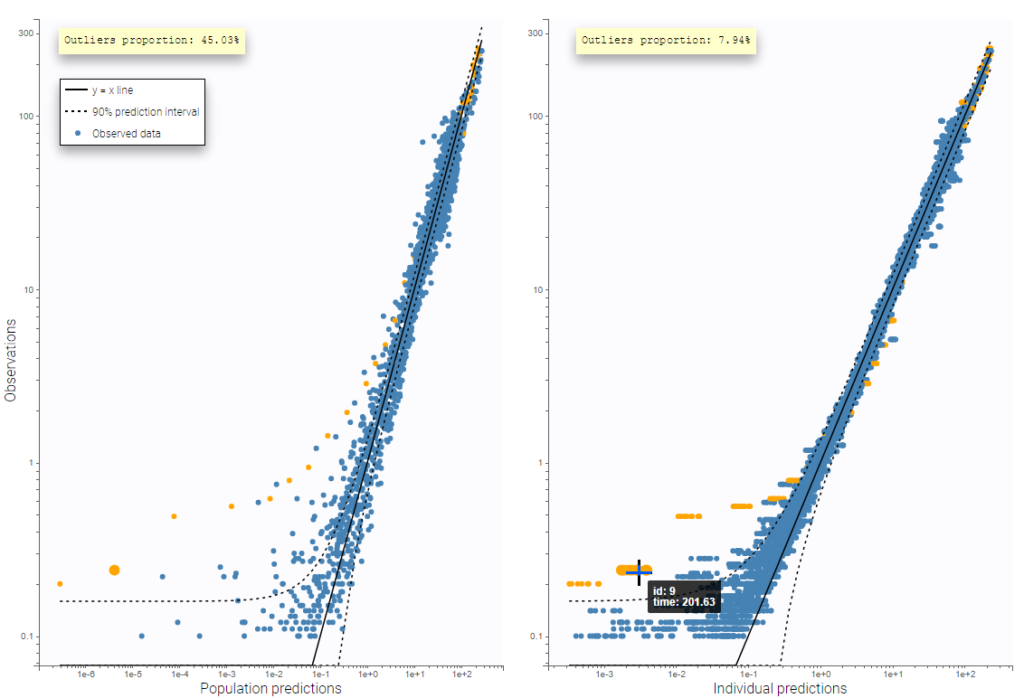

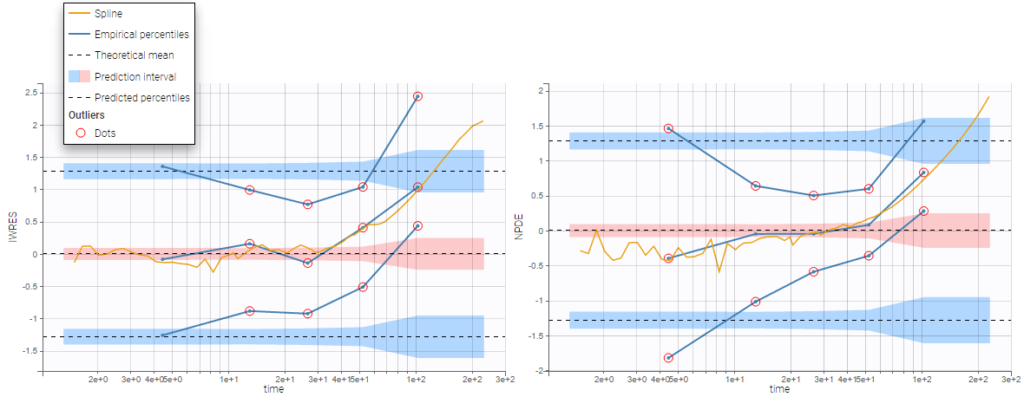

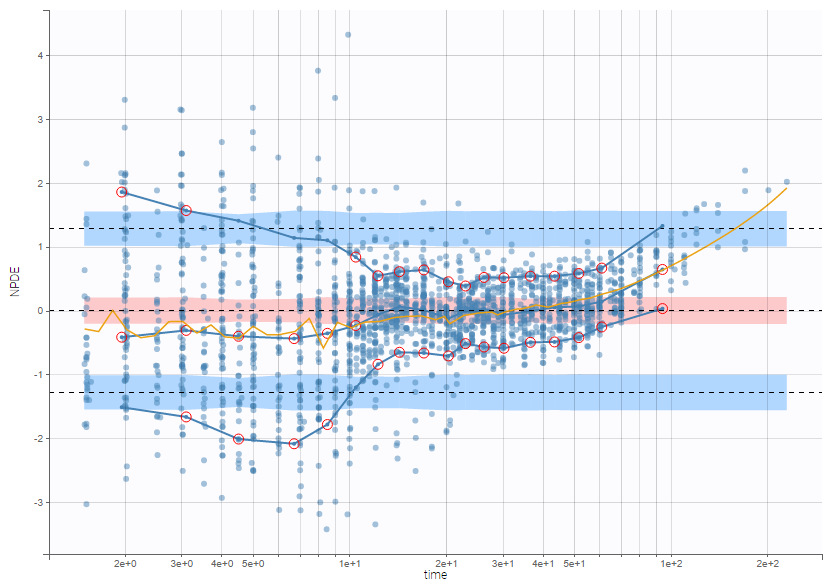

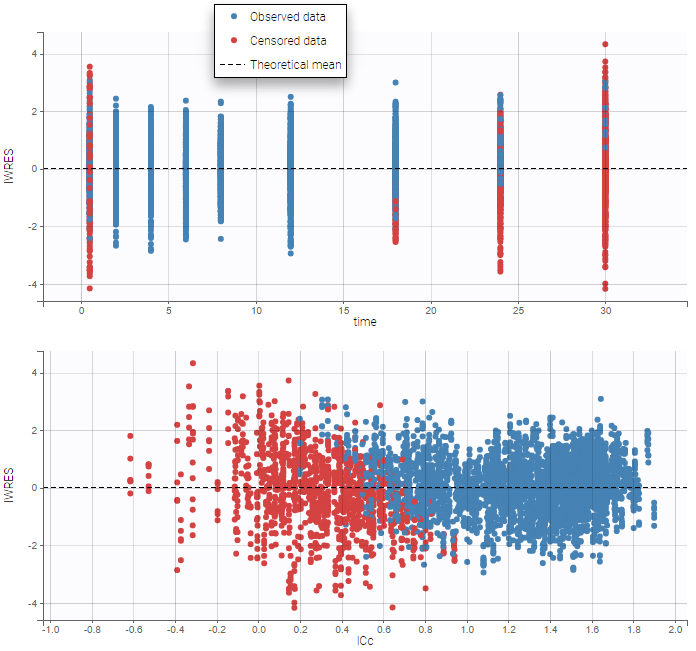

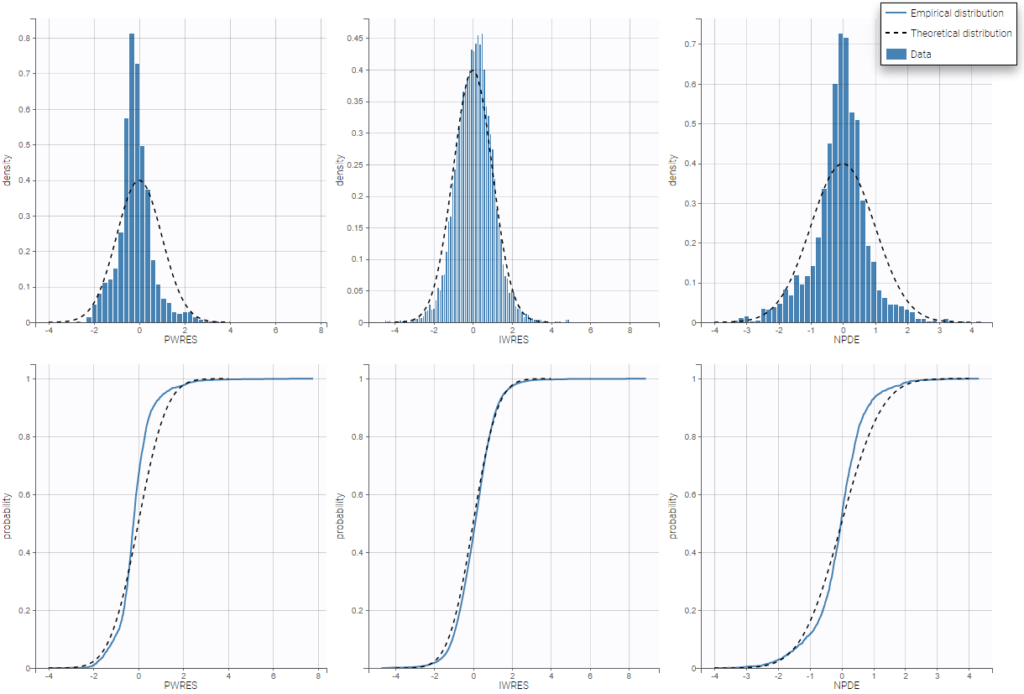

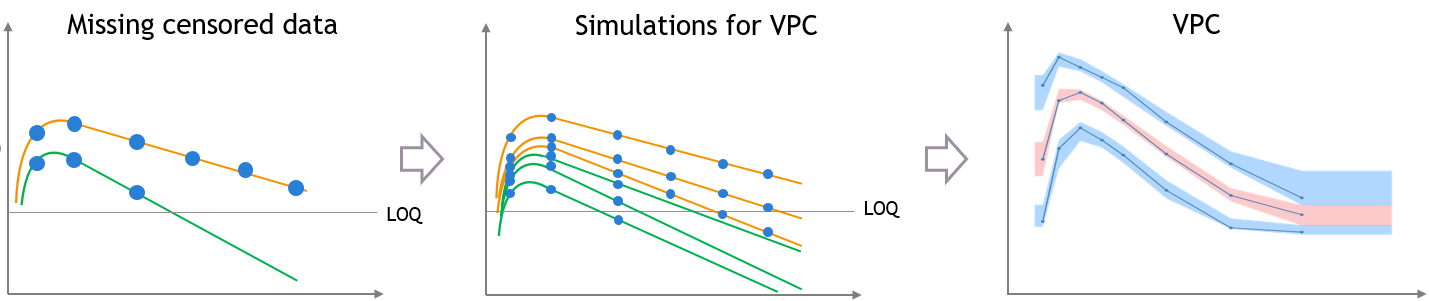

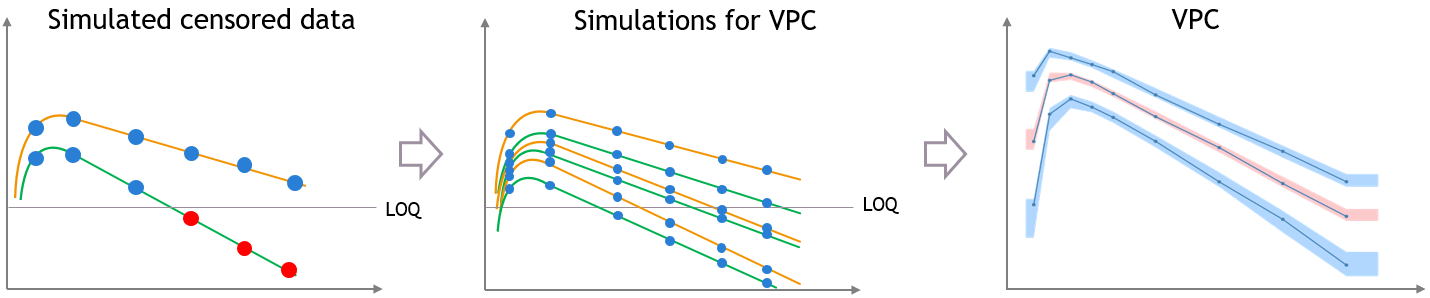

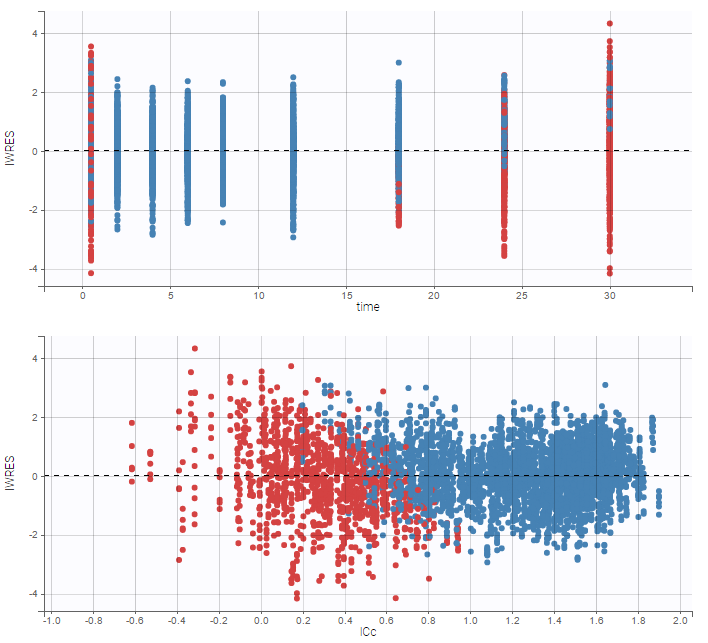

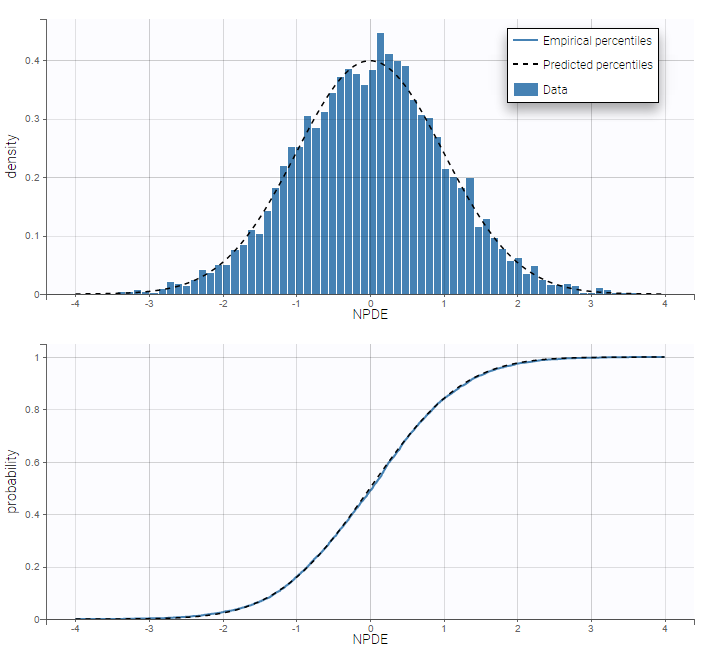

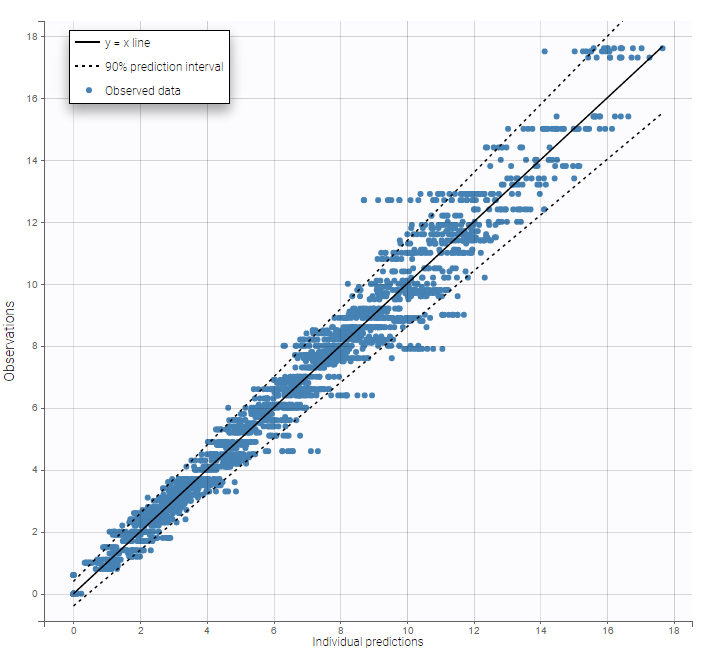

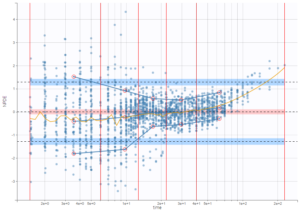

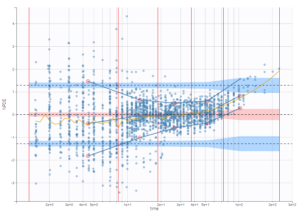

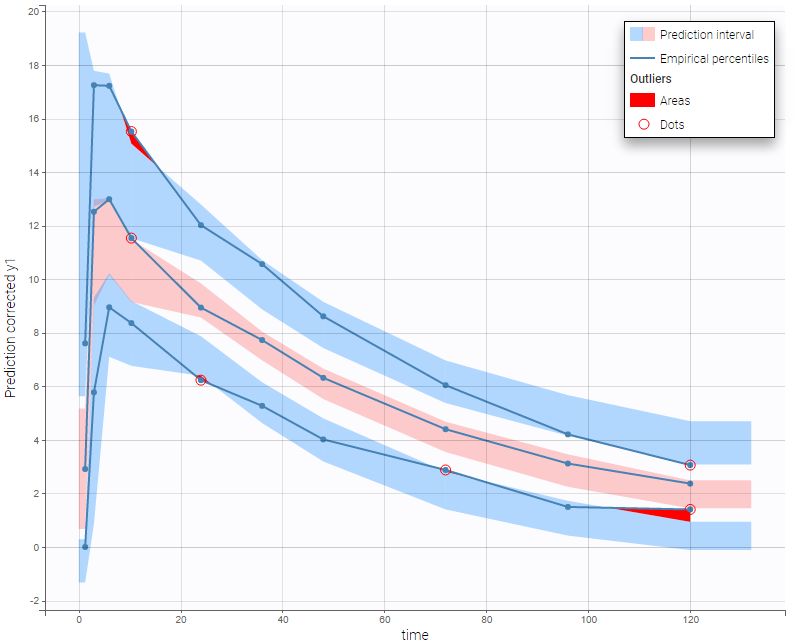

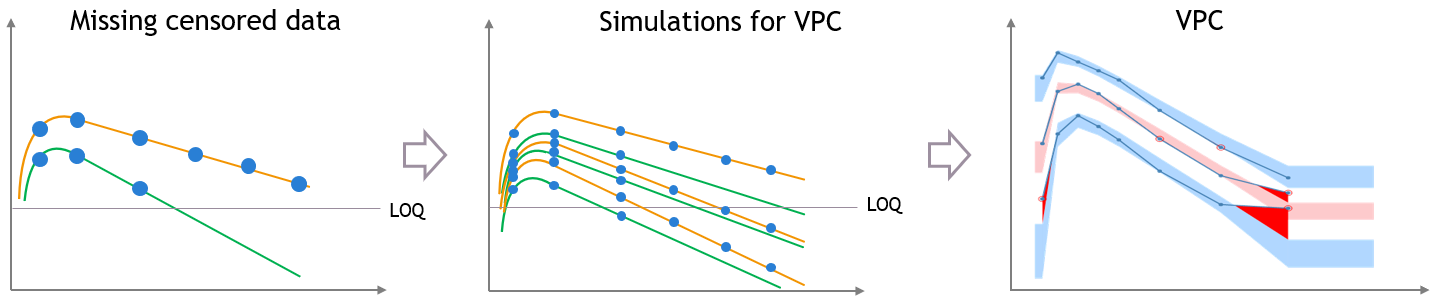

For diagnosis plots such as VPC, residuals of observations versus predictions, Monolix samples the BLQ data from the conditional distribution

$$p(y^{BLQ} | y^{non BLQ}, \hat{\psi}, \hat{\theta})$$

where and

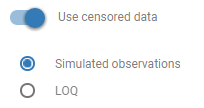

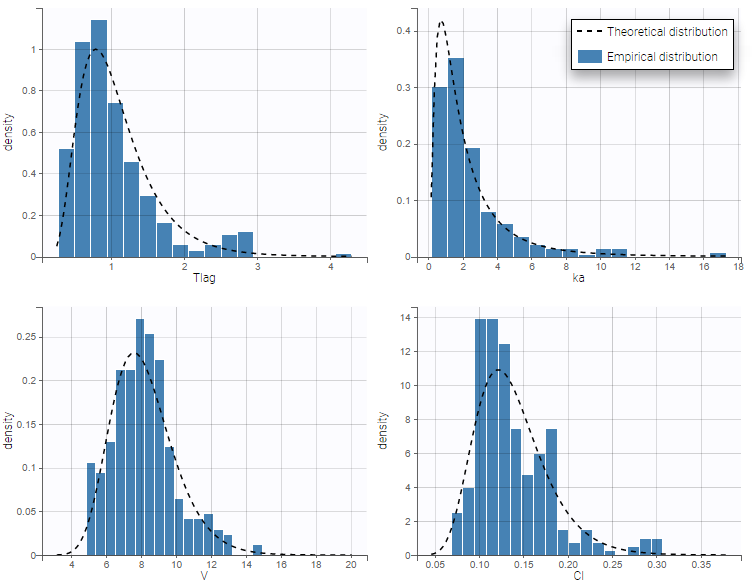

are the estimated population and individual parameters. This is done by adding a residual error on top of the prediction, using a truncated normal distribution to make sure that the simulated BLQ remains within the censored interval. This is the most efficient way to take into account the complete information provided by the data and the model for diagnosis plots such as VPCs:

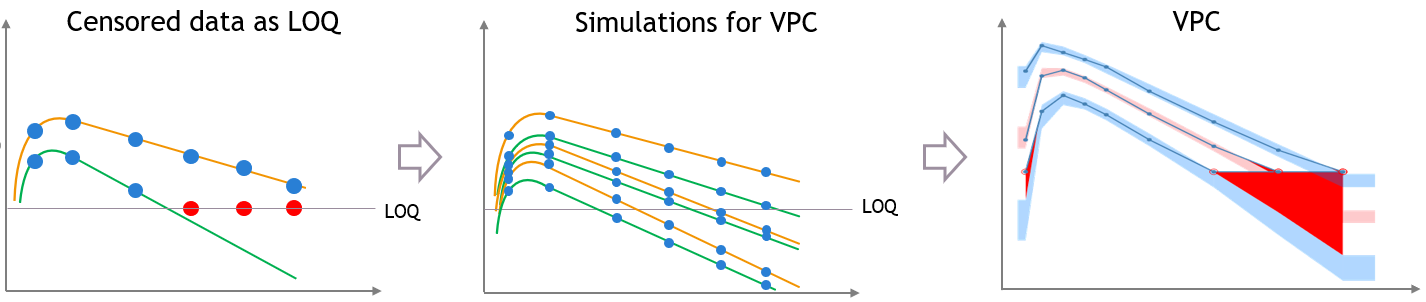

A strong bias appears if LLOQ is used instead for the BLQ data (if you choose LOQ instead of simulated in the display frame of the settings) :

Notice that ignoring the BLQ data entails a loss of information as can be seen below (if you choose no in the “Use BLQ” toggle):

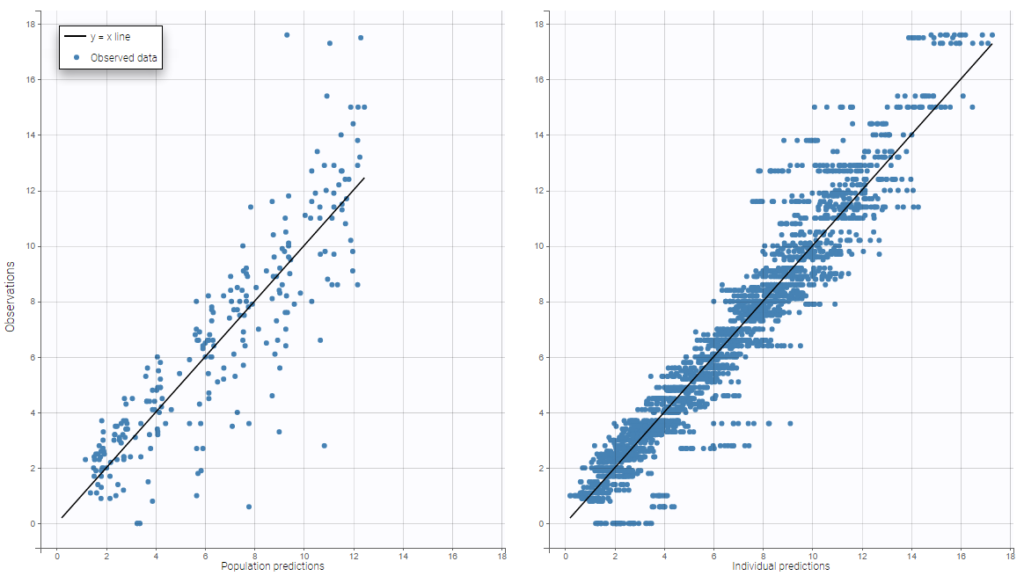

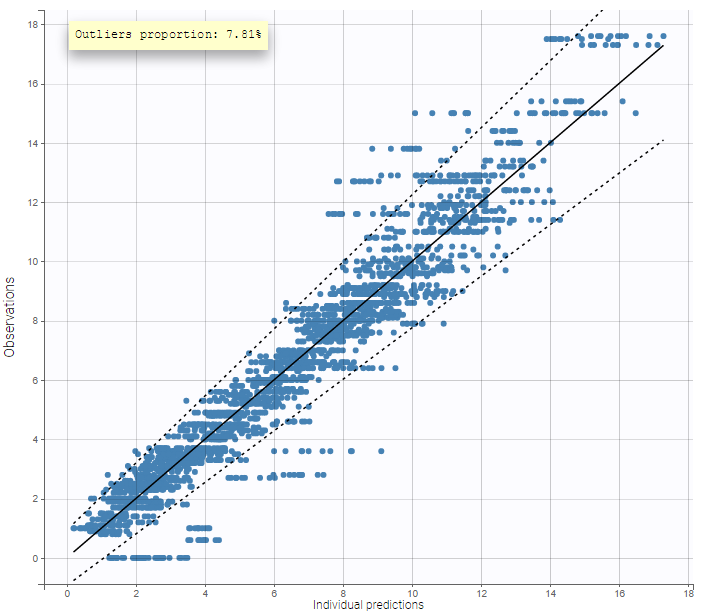

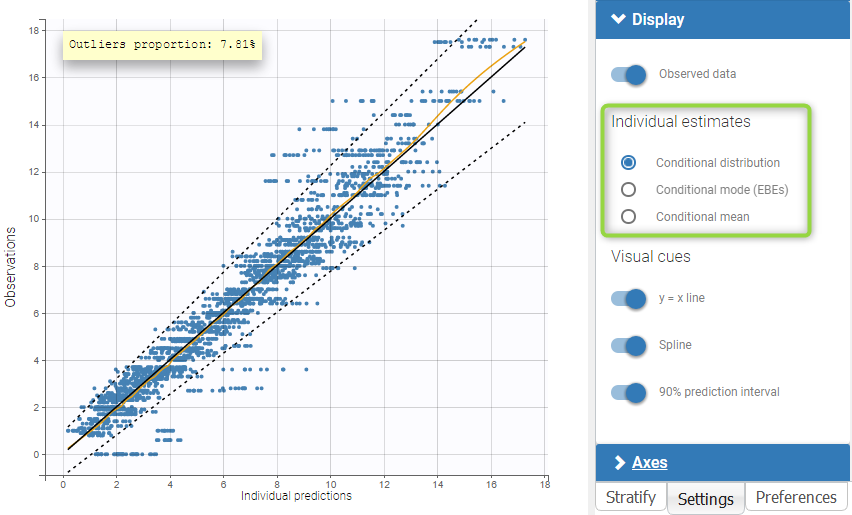

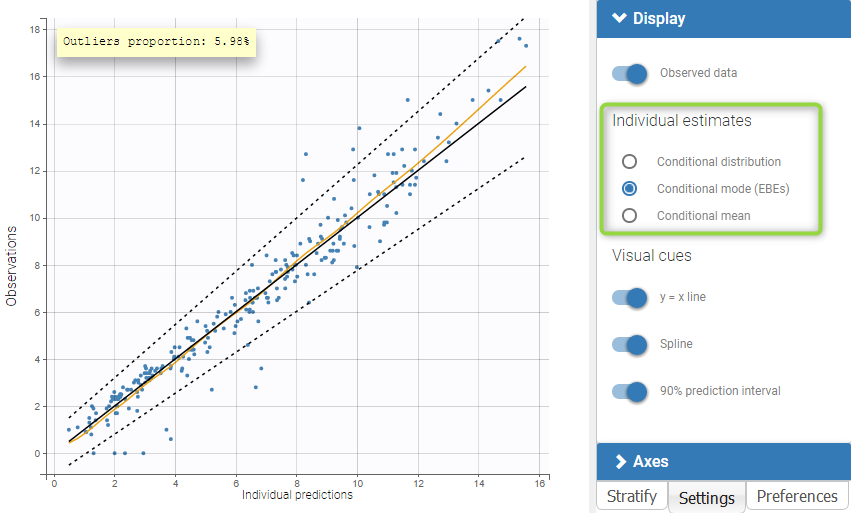

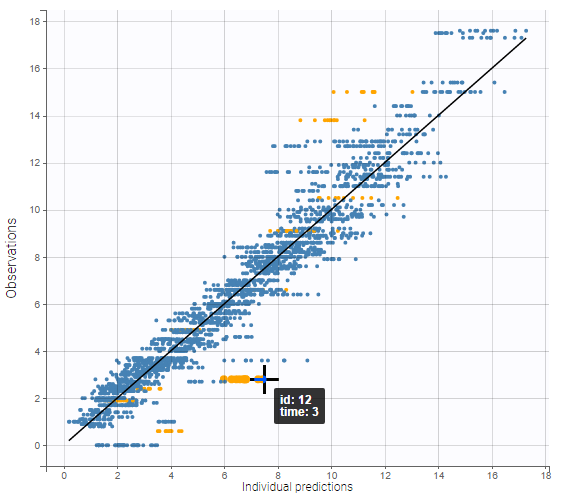

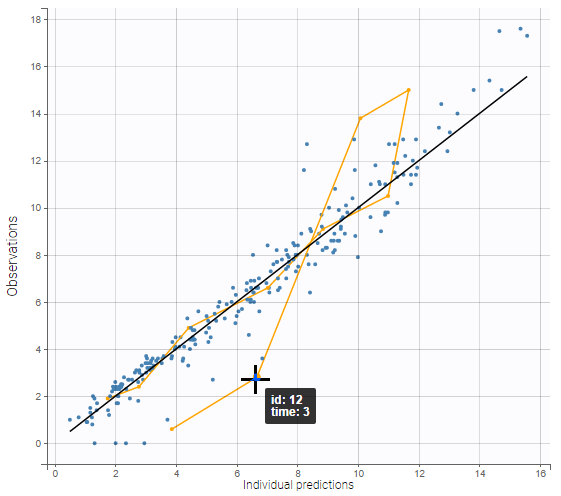

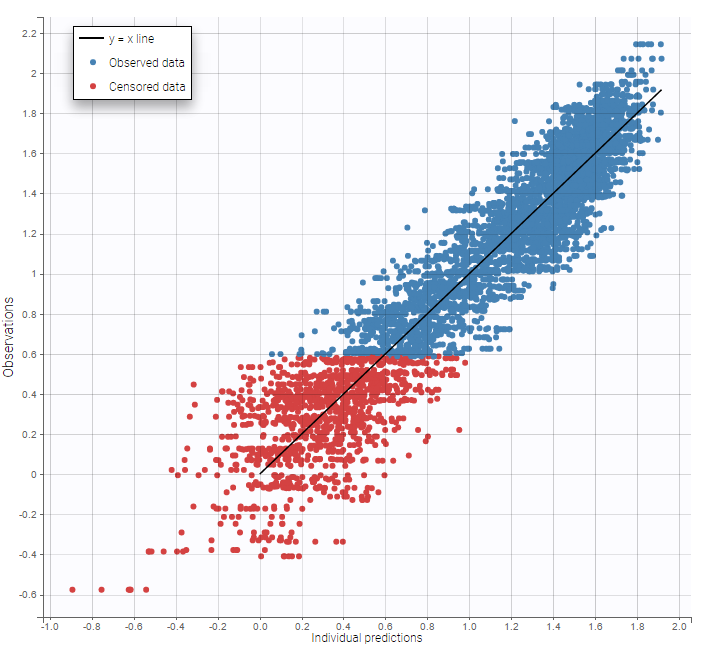

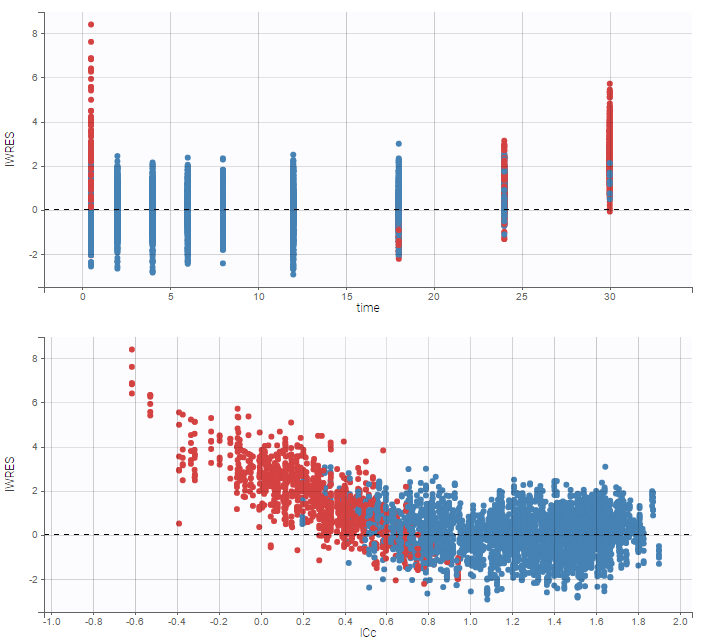

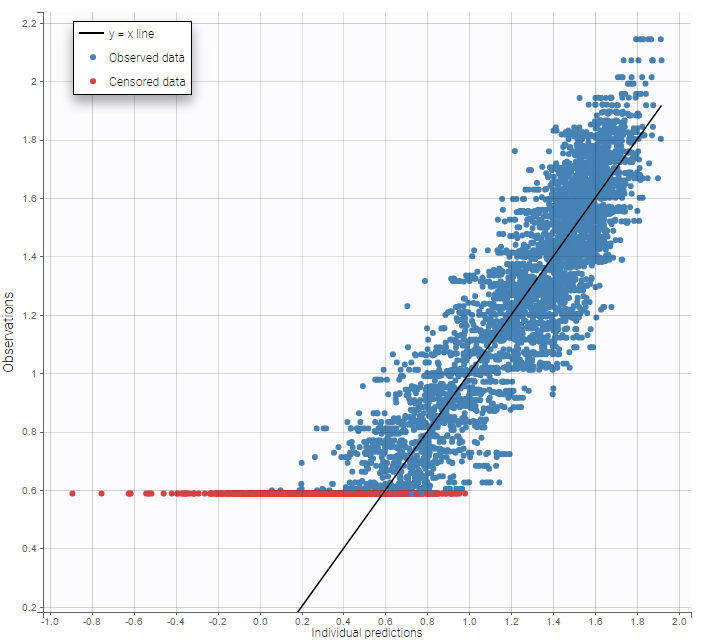

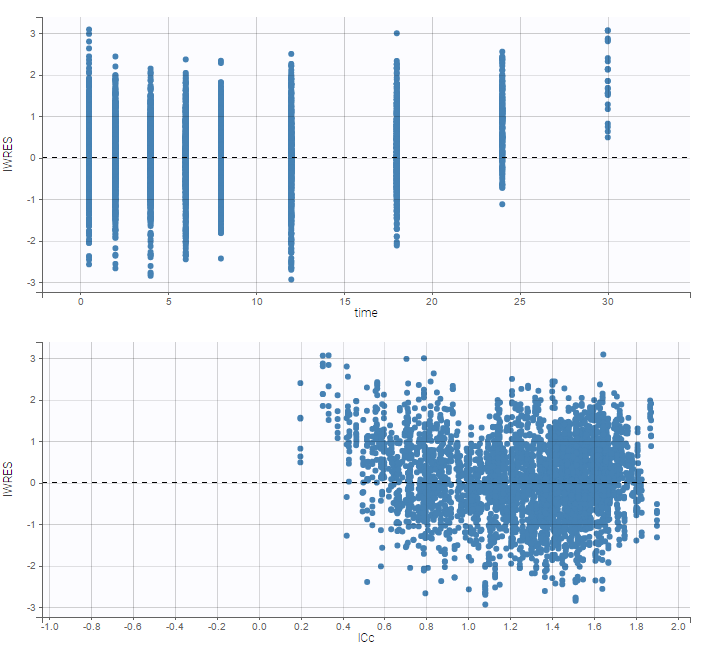

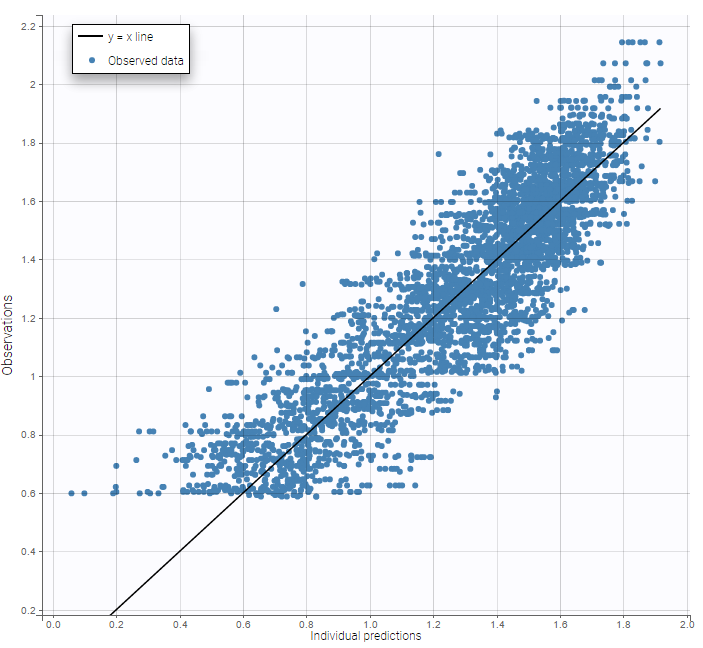

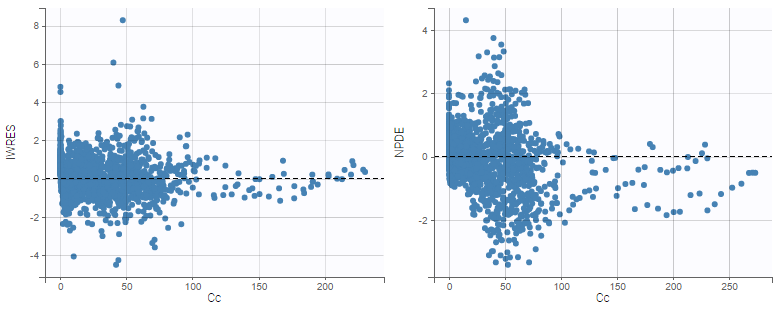

As can be seen below, imputed BLQ data is also used for residuals (IWRES on the left) and for observations versus predictions (on the right)

|

|

|---|

More on these diagnosis plots

Impact of the BLQ in residuals and observations versus predictions plots

A strong bias appears if LLOQ is used instead for the BLQ data for these two diagnosis plots:

|

|

|---|

while ignoring the BLQ data entails a loss of information:

|

|

|---|

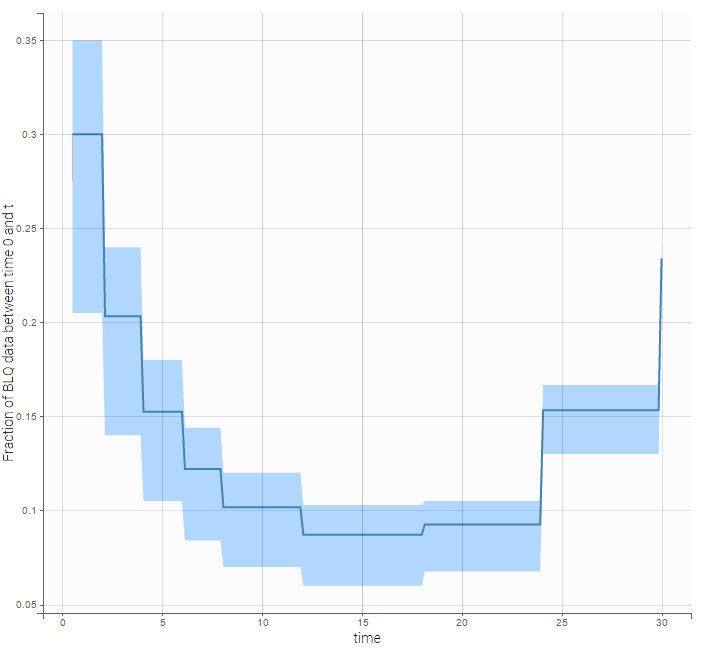

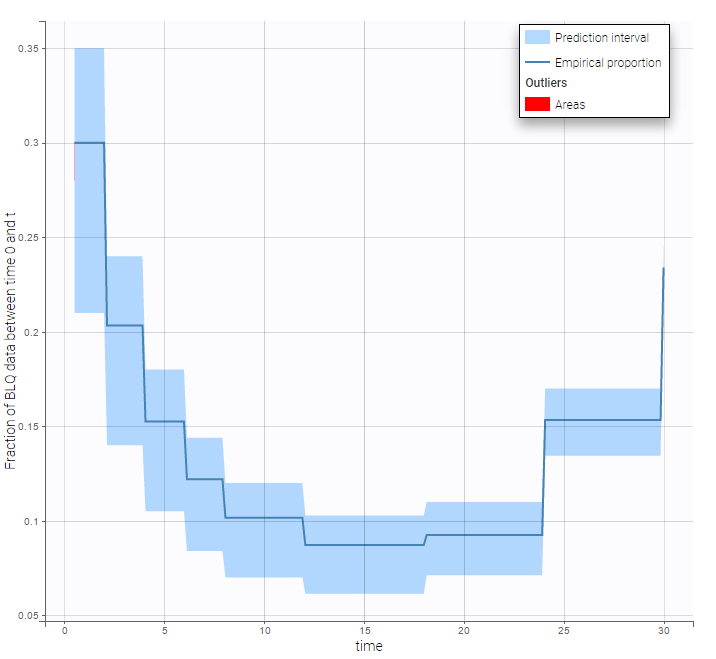

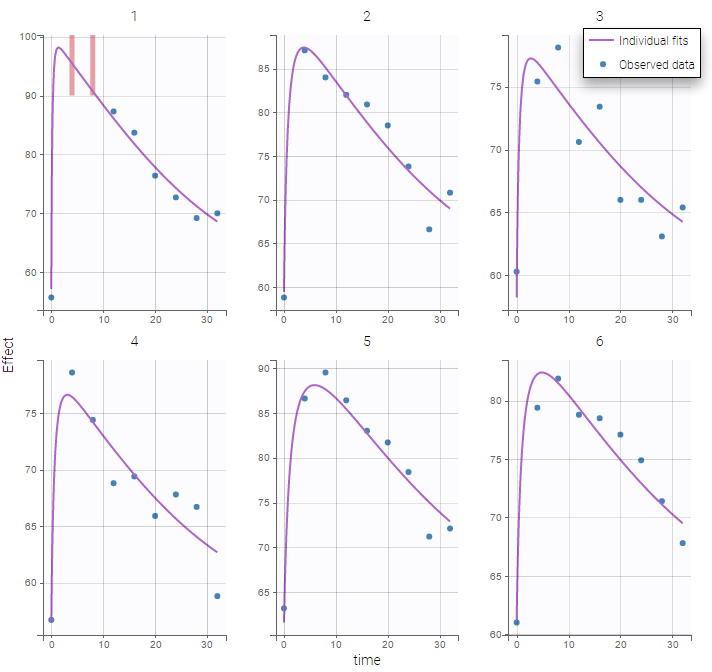

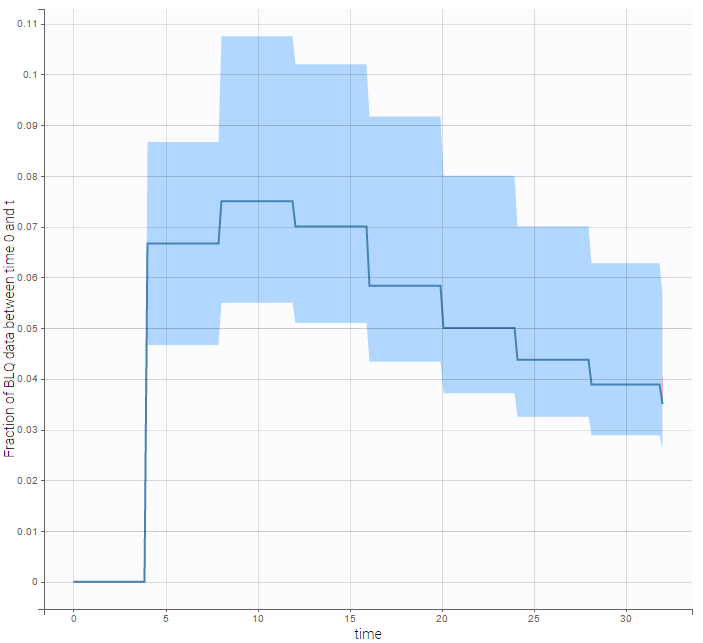

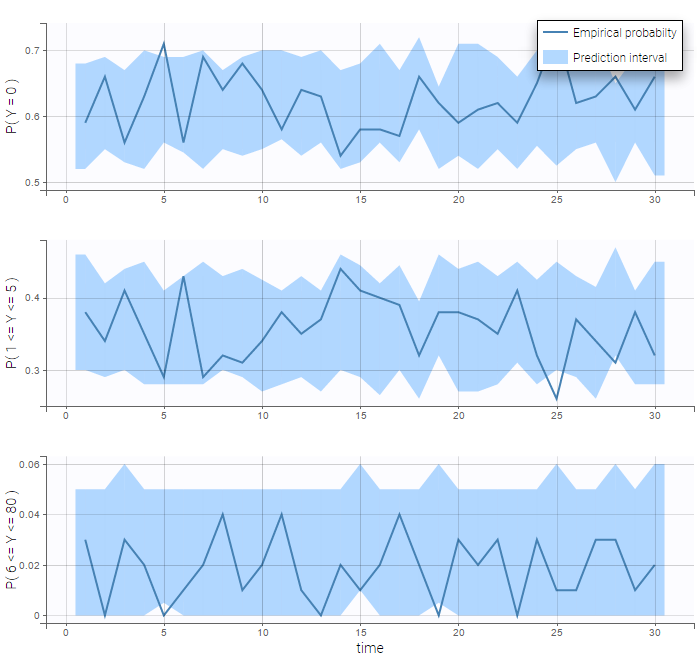

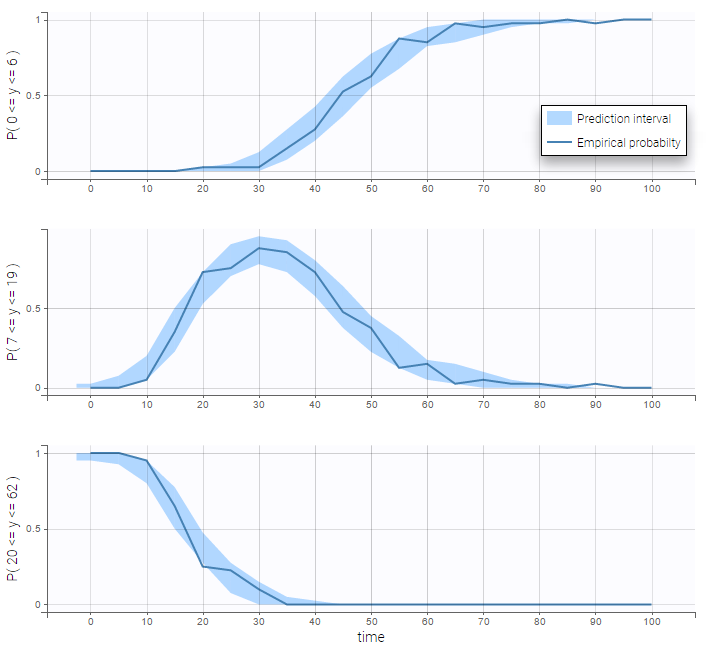

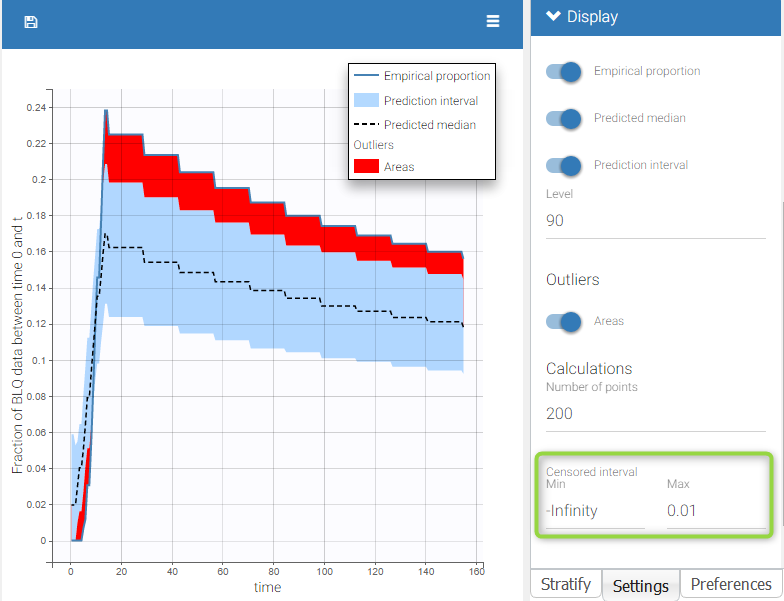

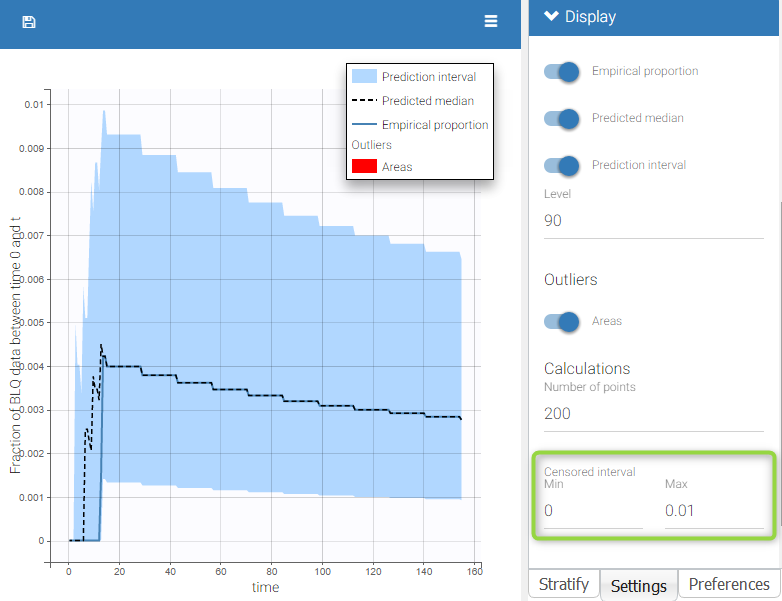

BLQ predictive checks

The BLQ predictive check is a diagnosis plot that displays the fraction of cumulative BLQ data (blue line) with a 90% prediction interval (blue area).

Interval censored data

- censoring1_project (data = ‘censored1_data.txt’, model = ‘lib:oral1_1cpt_kaVk.txt’)

We use the original concentrations in this project. Then, BLQ data should be treated as interval censored data since a concentration is know to be positive. In other word, a data reported as BLQ data means that the (non reported) measured concentration is between 0 and 1.8mg/l. The value in the observation column 1.8 indicates the value, the value in the CENSORING column indicates that the value in the observation column is the upper bound. An additional column LIMIT reports the lower limit of the censored interval (0 in this example):

Remarks

- if this column is missing, then BLQ data is assumed to be left-censored data that can take any positive and negative value below LLOQ.

- the value of the limit can vary between observations of the same subject.

Monolix will use this additional information to estimate the model parameters properly and to impute the BLQ data for the diagnosis plots.

Plot of individual fits now displays LLOD at 1.8 with a red band when a PK data is censored. We see that the band lower limit is at 0 as defined in the limit column.

PK data below a lower limit of quantification or below a limit of detection

- censoring2_project (data = ‘censored2_data.txt’, model = ‘lib:oral1_1cpt_kaVk.txt’)

Plot of individual fits now displays LLOQ or LLOD with a red band when a PK data is censored. We see that the band lower limits depend on the observation.

Plot of individual fits now displays LLOQ or LLOD with a red band when a PK data is censored. We see that the band lower limits depend on the observation.

PK data below a lower limit of quantification and PD data above an upper limit of quantification

- censoring3_project (data = ‘censored3_data.txt’, model = ‘pkpd_model.txt’)

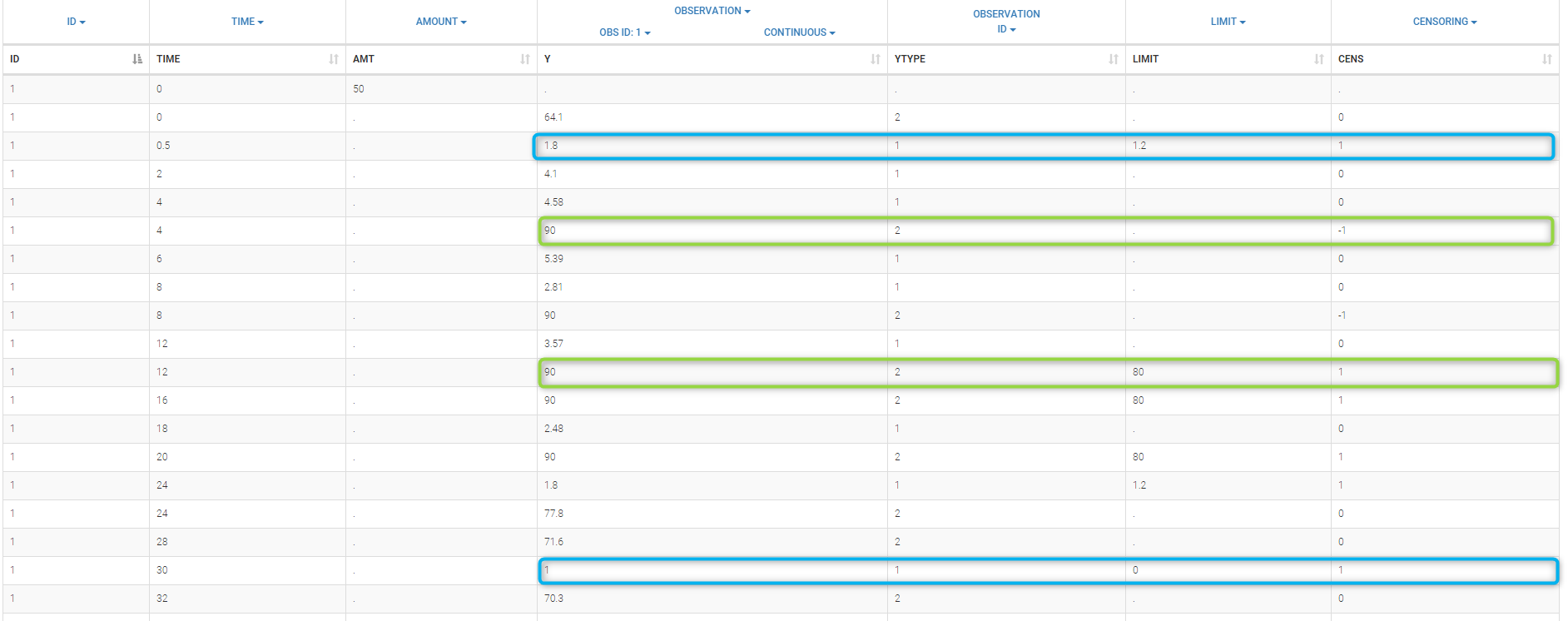

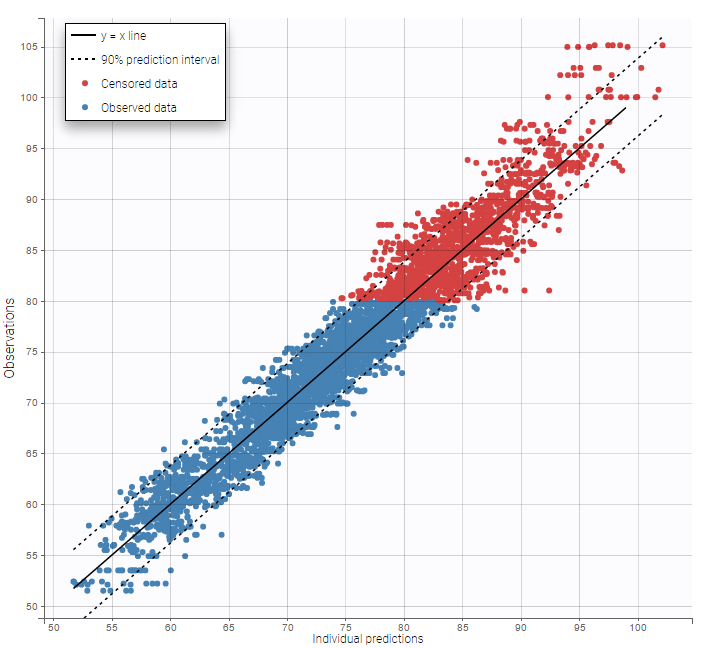

We work with PK and PD data in this project and assume that the PD data may be right censored and that the upper limit of quantification is ULOQ=90. We use CENS=-1 to indicate that an observation is right censored. In such case, the PD data can take any value above the upper limit reported in column Y (here the YTYPE column of type OBSERVED ID defines the type of observation, YTYPE=1 and YTYPE=2 are used respectively for PK and PD data):

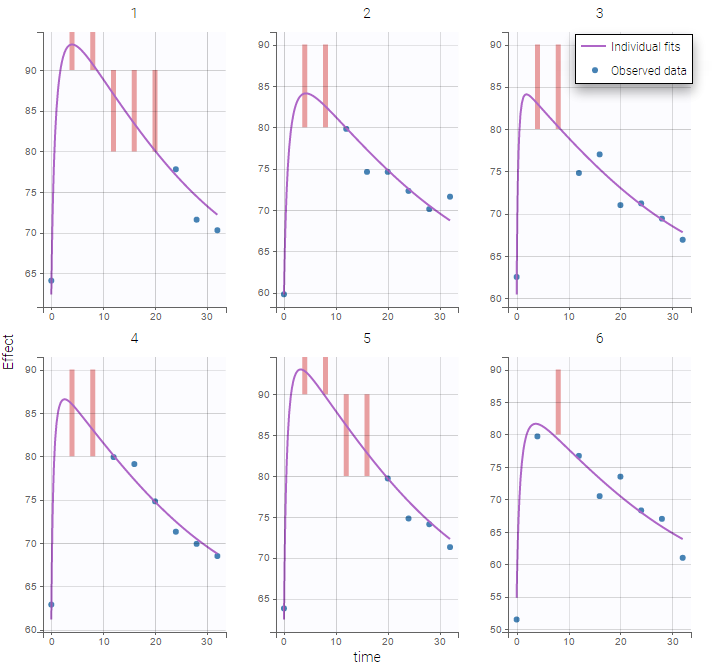

Plot of individual fits for the PD data now displays ULOQ and the predicted PD profile:

Plot of individual fits for the PD data now displays ULOQ and the predicted PD profile:

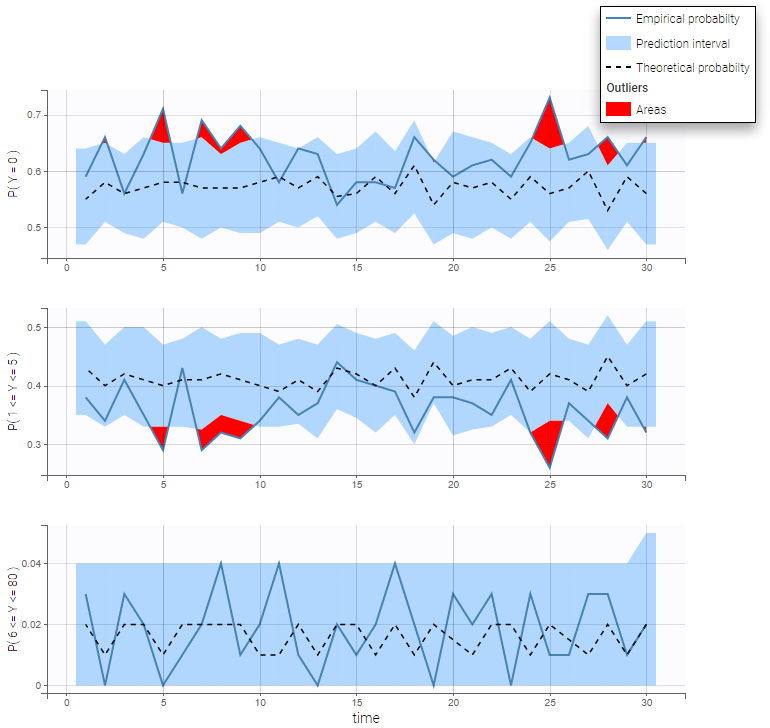

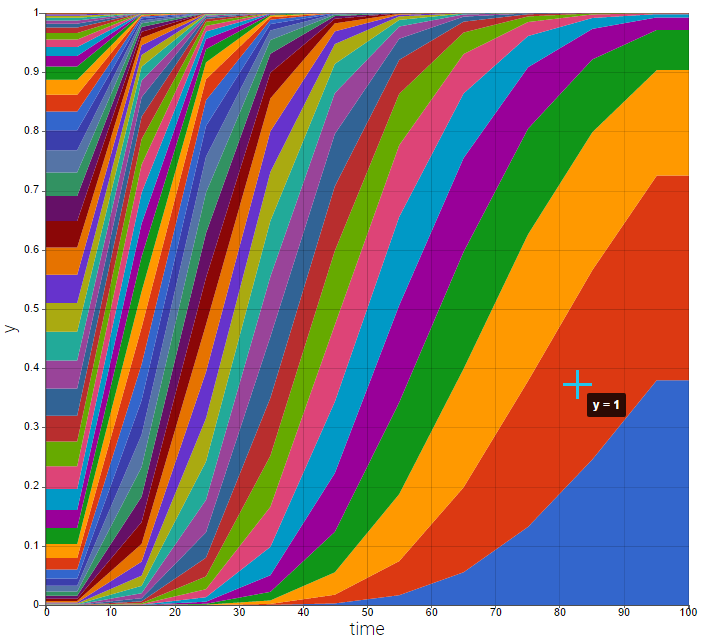

We can display the cumulative fraction of censored data both for the PK and the PD data (on the left and right respectively):

|

|

|---|

Combination of interval censored PK and PD data

- censoring4_project (data = ‘censored4_data.txt’, model = ‘pkpd_model.txt’)

We assume in this example

- 2 different censoring intervals(0,1) and (1.2, 1.8) for the PK,

- a censoring interval (80,90) and right censoring (>90) for the PD.

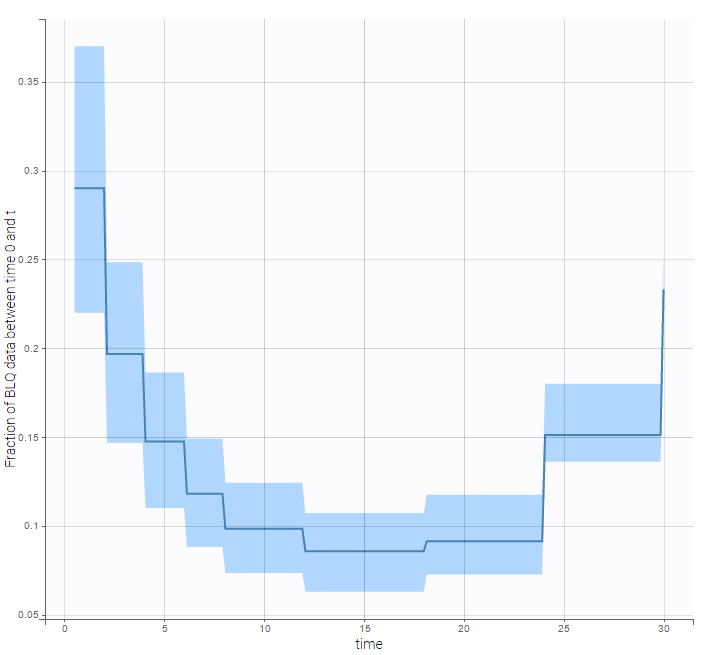

Combining columns CENS, LIMIT and Y allow us to combine efficiently these different censoring processes:

This coding of the data means that, for subject 1,

- PK data is between 0 and 1 at time 30h (second blue frame),

- PK data is between 1.2 and 1.8 at times 0.5h and 24h (first blue frame for time .5h),

- PD data is between 80 and 90 at times 12h and 16h (second green frame for time 12h),

- PD data is above 90 at times 4h and 8h (first green frame for time 4h).

Plot of individual fits for the PK and the PD data displays the different limits of these censoring intervals (PK on the left and PD on the right):

|

|

|---|

Other diagnosis plots, such as the plot of observations versus predictions, adequately use imputed censored PK and PD data:

|

|

|---|

Case studies

- 8.case_studies/hiv_project (data = ‘hiv_data.txt’, model = ‘hivLatent_model.txt’)

- 8.case_studies/hcv_project (data = ‘hcv_data.txt’, model = ‘hcvNeumann98_model_latent.txt’)

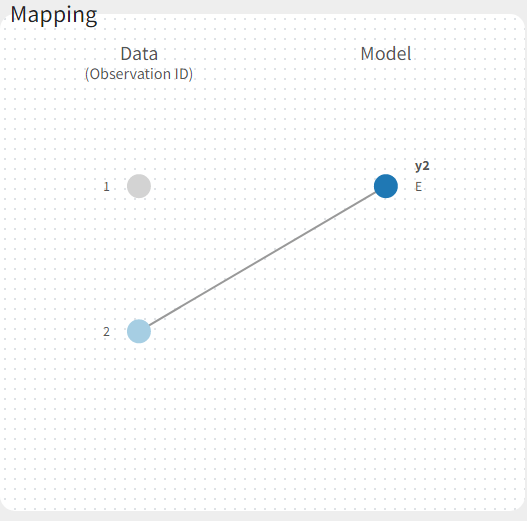

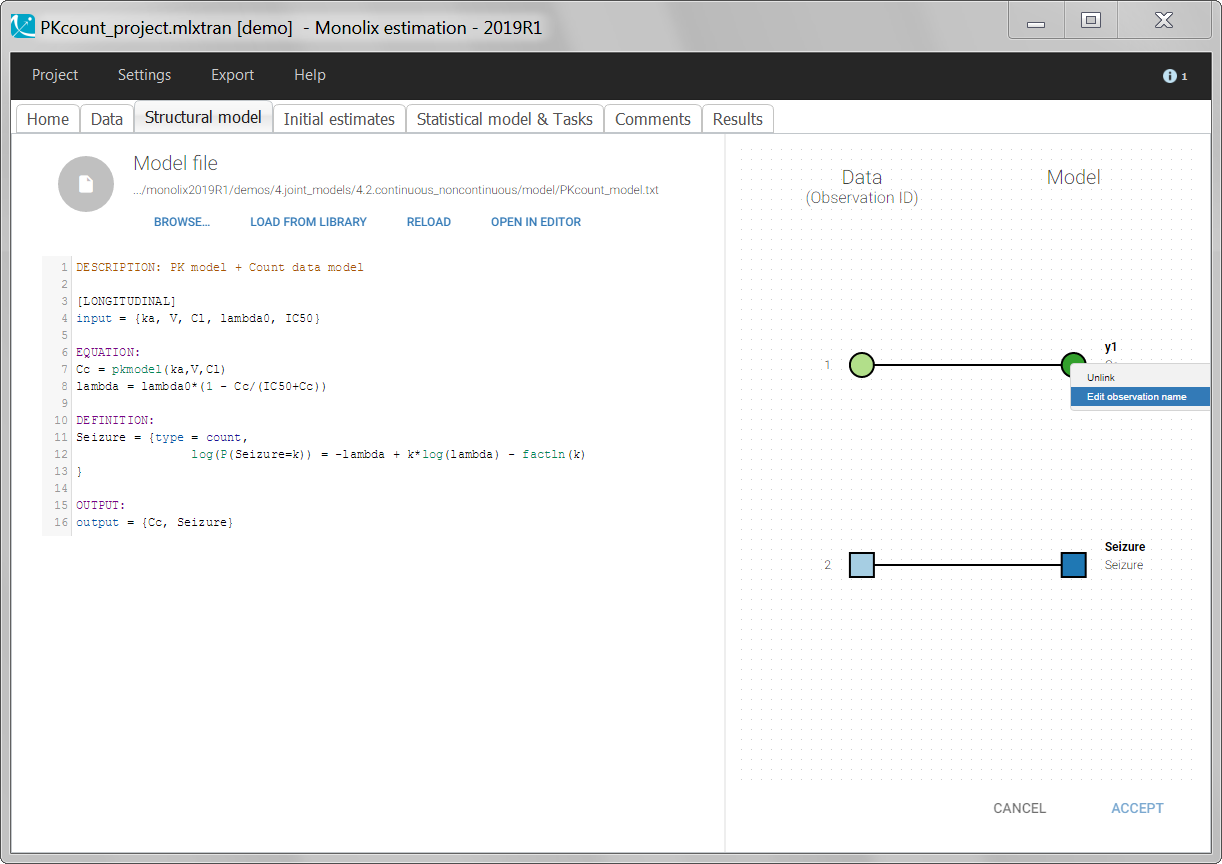

2.6.Mapping between the data and the model

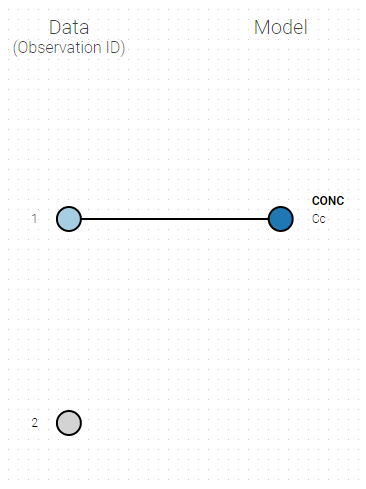

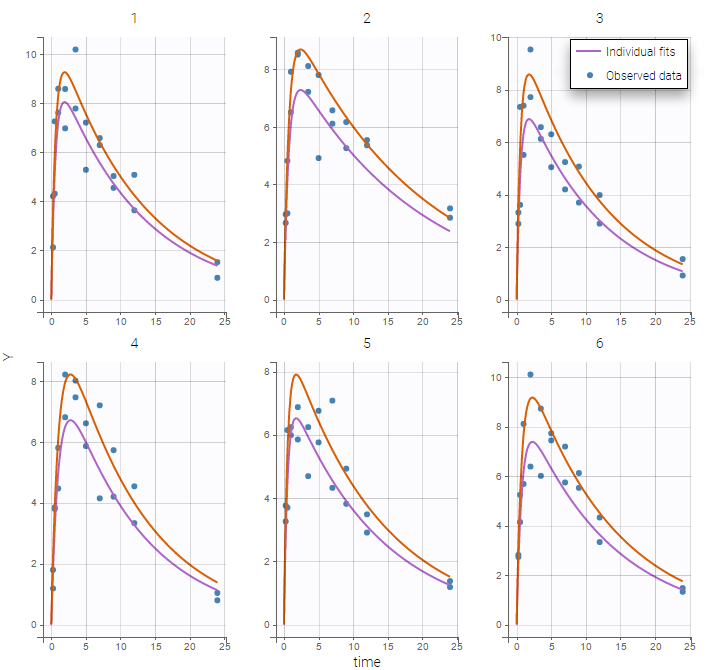

Starting from the 2019 version, it is possible to change the mapping between the data set observations ids and the structural model output. By default and in previous versions, the mapping is done by order, i.e. the first output listed in the output= statement of the model is mapped to the first OBSERVATION ID (ordered alphabetically). It is possible with the interface to set exactly which model output is mapped to which data output. Model output or data outputs can be left unused.

Changing the mapping

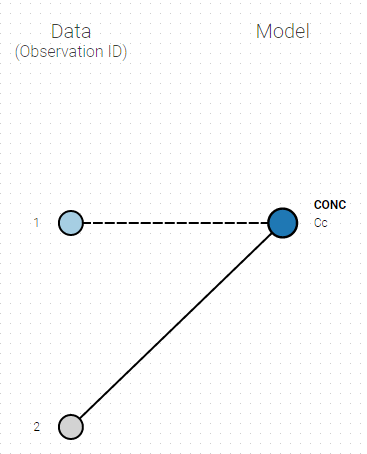

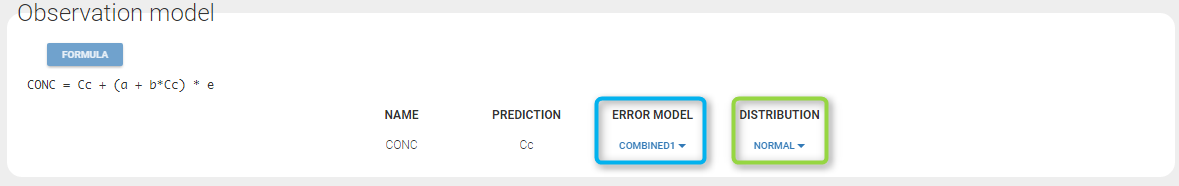

If you have more output in the data set (i.e more OBSERVATION IDs) than in the structural model, you can set which data output you will use in the project. In the example below there are two outputs in the data set (managed by the OBSERVATION ID column) and only one output in the structural model, Cc. By default the following mapping is proposed: the data with observation id ‘1’ is mapped to the modle prediction ‘Cc’. The model observation (with error model) is called ‘CONC’ (the name of the OBSERVATION column, can be edited):

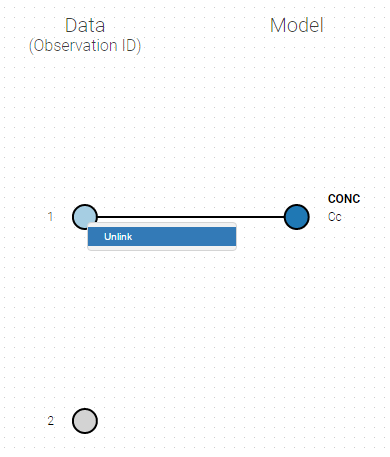

To set the data output to use to observation id ‘2’, you can either:

- Unlink by clicking on either the dot representing the output ‘1’ of the Data or ‘Cc’ of the structural model, and then draw the line between ‘2’ and ‘Cc’ (as can be seen on the figure below on the left)

- Directly draw a line from ‘2’ to ‘Cc’ (as can be seen on the figure below on the right). This will automatically undo the link between ‘1’ and ‘Cc’.

|

|

|---|

And click on the button ACCEPT on the bottom on the window to apply the changes.

The same possibility is proposed if you have more outputs in the structural model, compared to the number of observation ids. If you have a TMDD model with both the free and the total ligand concentration listed as model output and one type of measurement, you can map either the free or the total ligand as can be seen on the following figure with the same actions as described above.

Several types of outputs

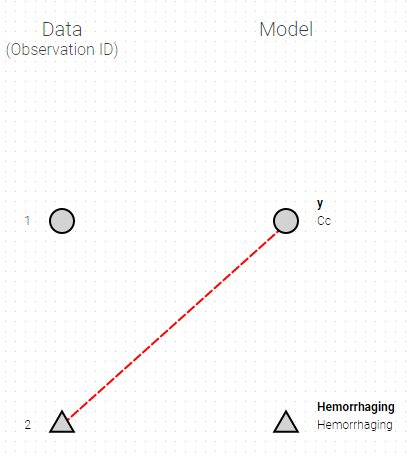

The mapping is only possible between outputs of same nature (continuous / count-categorical / event), i.e. it is only possible to map a continuous output with a continuous output of the structural model. Thus, mapping a continuous output with a discrete or a time-to-event is not possible. If you try to link a forbidden combination, the line connecting line will be displayed in red as in the following figure

The type of output is indicated via the shapes:

- continuous outputs are displayed as circles

- categorical/count outputs are displayed as squares

- event outputs are displayed as triangles

Changing the observation name

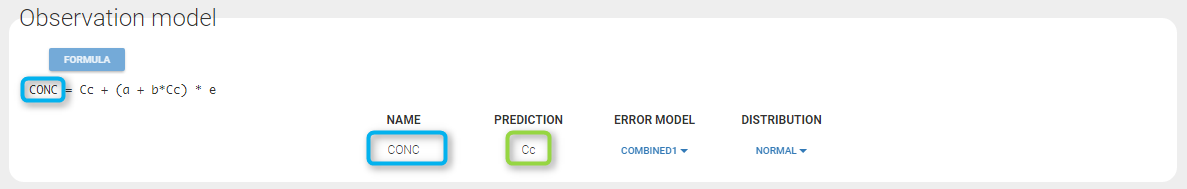

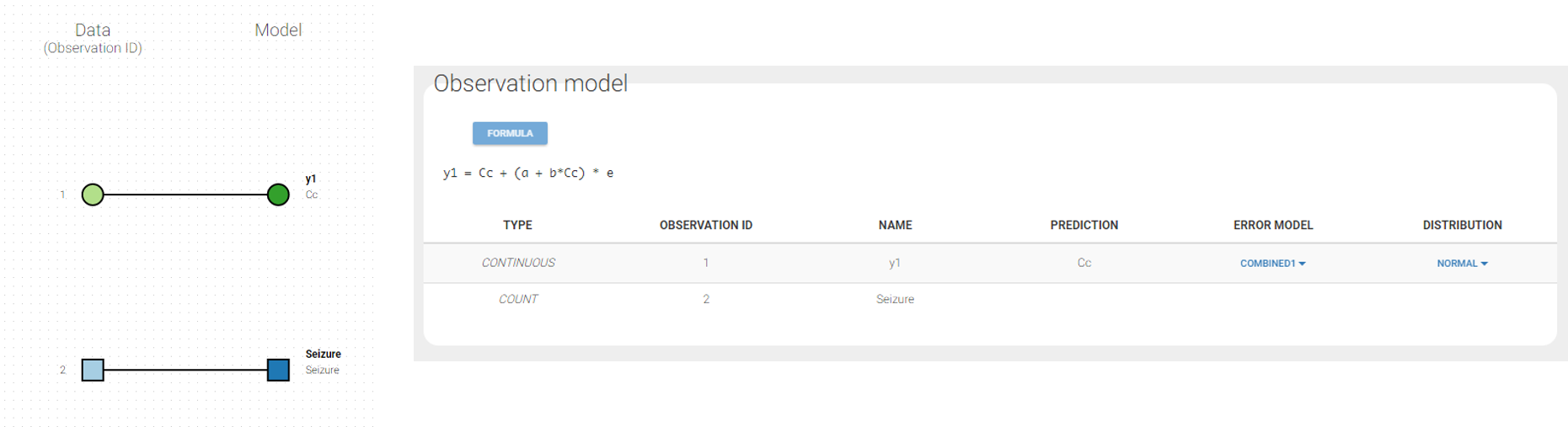

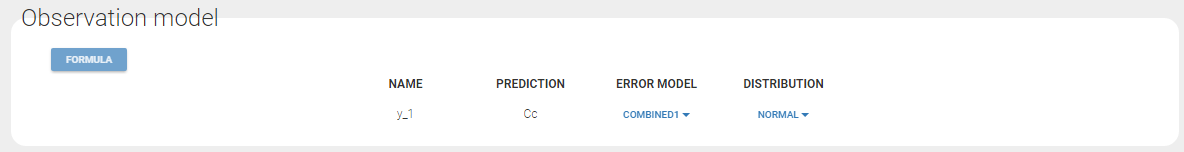

In the example below, ‘1’ is the observation id used in the data set to identify the data to use, ‘Cc’ is the model output (a prediction, without residual error) and ‘y1’ the observation (with error). ‘y1’ represents the data with observation id ‘1’ and it appears in the labels/legends of the plots. These elements are related by observation model, which formula can be displayed.

For count/categorical and event model outputs, the model observation is defined in the model file directly. The name used in the model file is reused in the mapping interface and cannot be changed.

For continuous outputs, the model file defines the name of the prediction (e.g ‘Cc’), while the model observation (e.g ‘y1’, with error) definition is done in the “Statistical model and tasks” tab of the interface. If there is only one model output, the default observation name is the header of the data set column tagged as OBSERVATION. In case of several model outputs, the observation names are y1, y2, y3, etc. The observation names for continuous outputs can be changed by clicking on the node and “edit observation name”:

3.Structural model

3.1.Libraries of models

- The PK library

- The PD and PKPD libraries

- The PK double absorption library

- The TMDD library

- The TTE library

- The Count library

- The TGI library

- A step-by-step example with the PK library

Objectives: learn how to use the Monolix libraries of models and use your own models.

Projects: theophylline_project, PDsim_project, warfarinPK_project, TMDD_project, LungCancer_project, hcv_project

For the definition of the structural model, the user can either select a model from the available model libraries or write a model itself using the Mlxtran language.

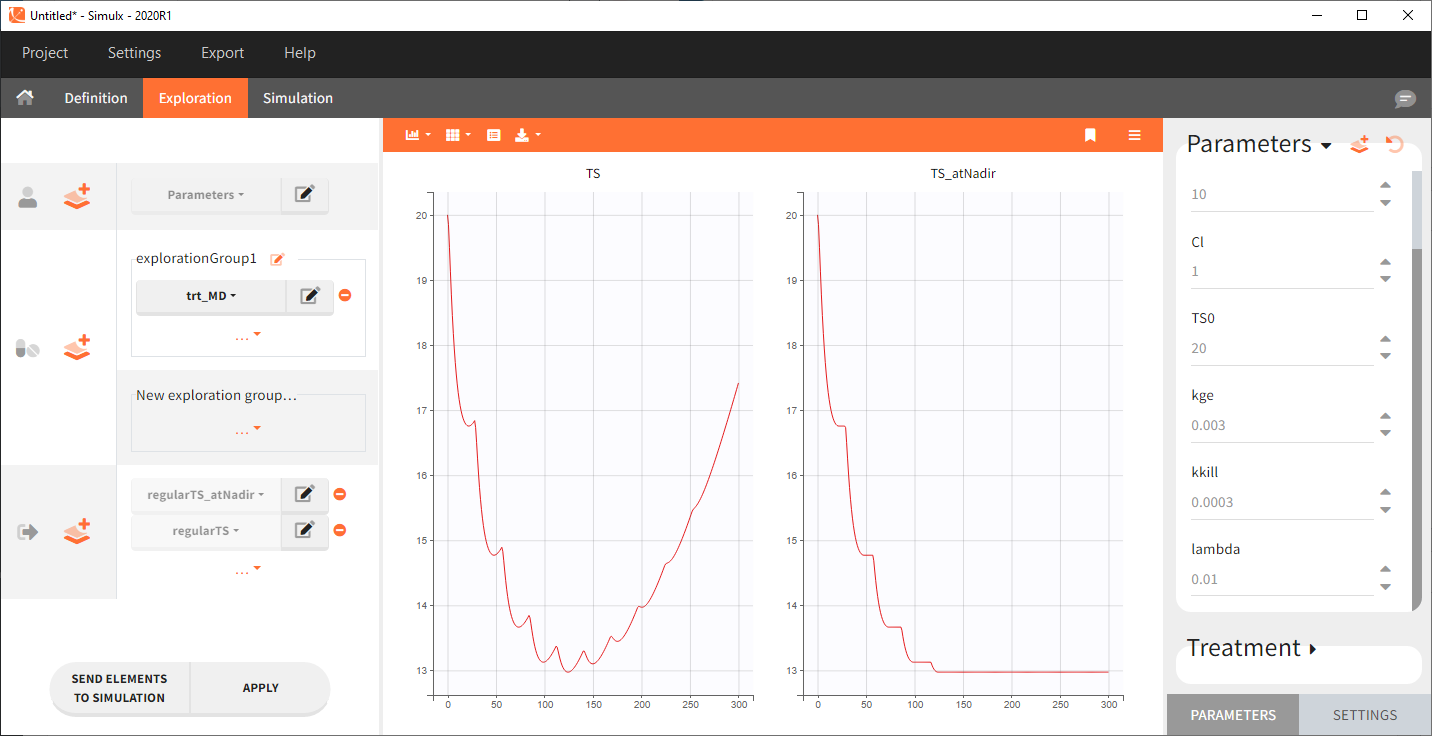

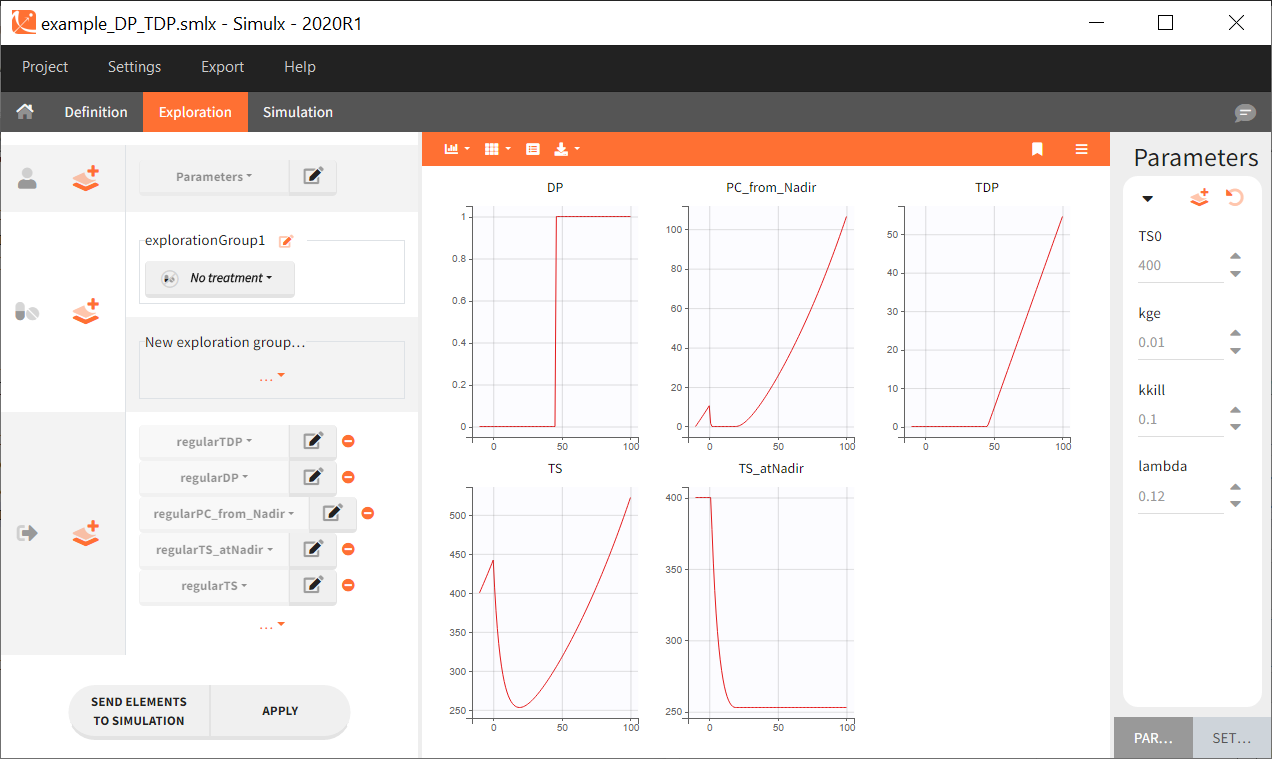

Discover how to easily choose a model from the libraries via step-by-step selection of its characteristics. An enriched PK, a PD, a joint PKPD, a target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD), and a time to-event (TTE) library are now available.

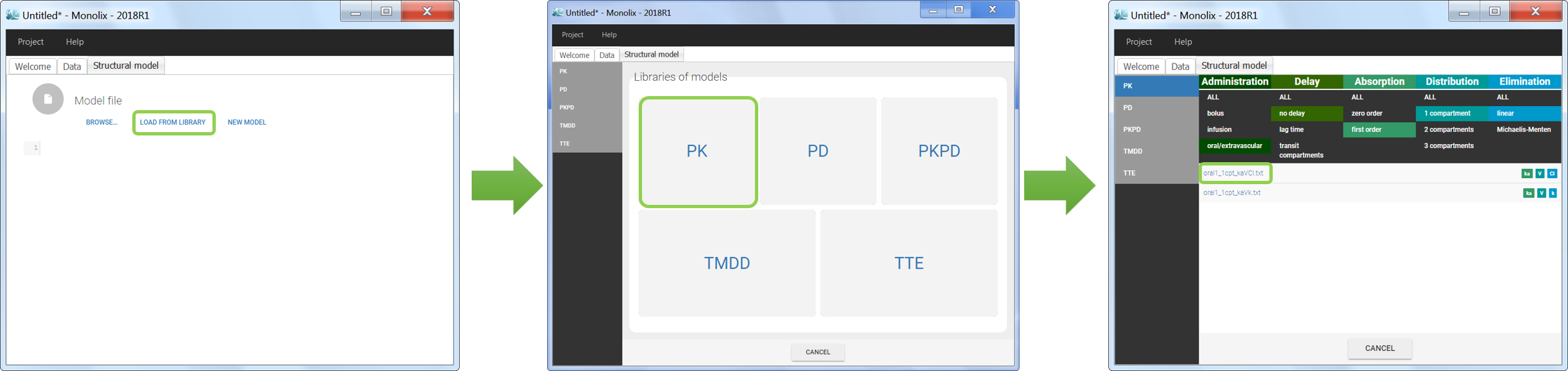

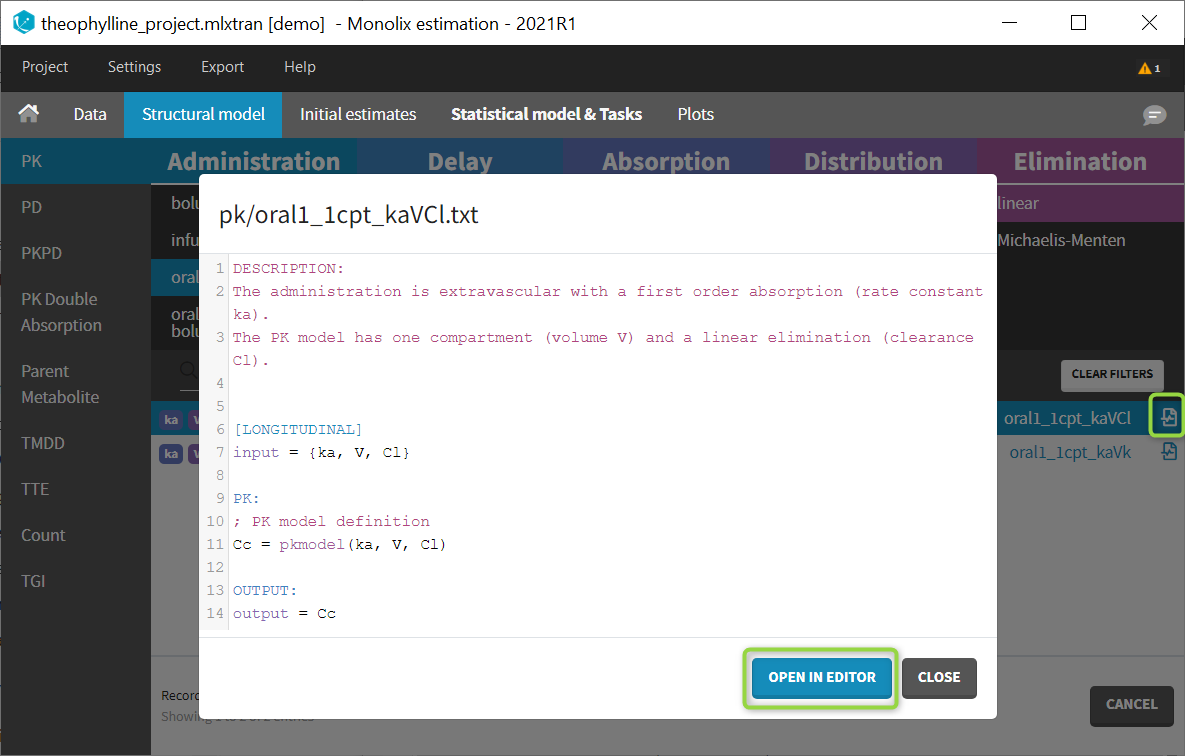

Model libraries

Five different model libraries are available in Monolix, which we will detail below. To use a model from the libraries, in the Structural model tab, click on Load from library and select the desired library. A list of model files appear, as well as a menu to filter them. Use the filters and indications in the file name (parameters names) to select the model file you need.

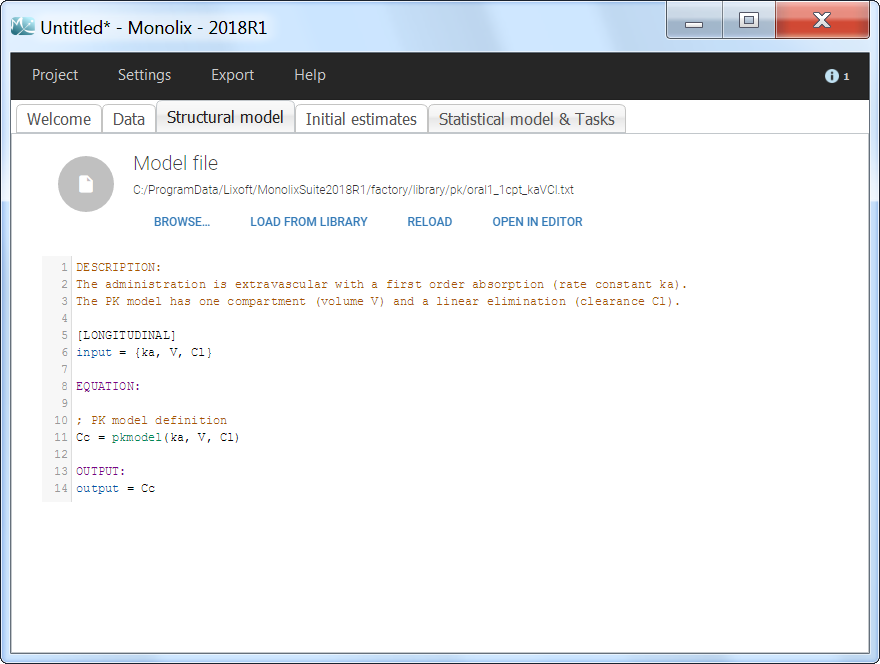

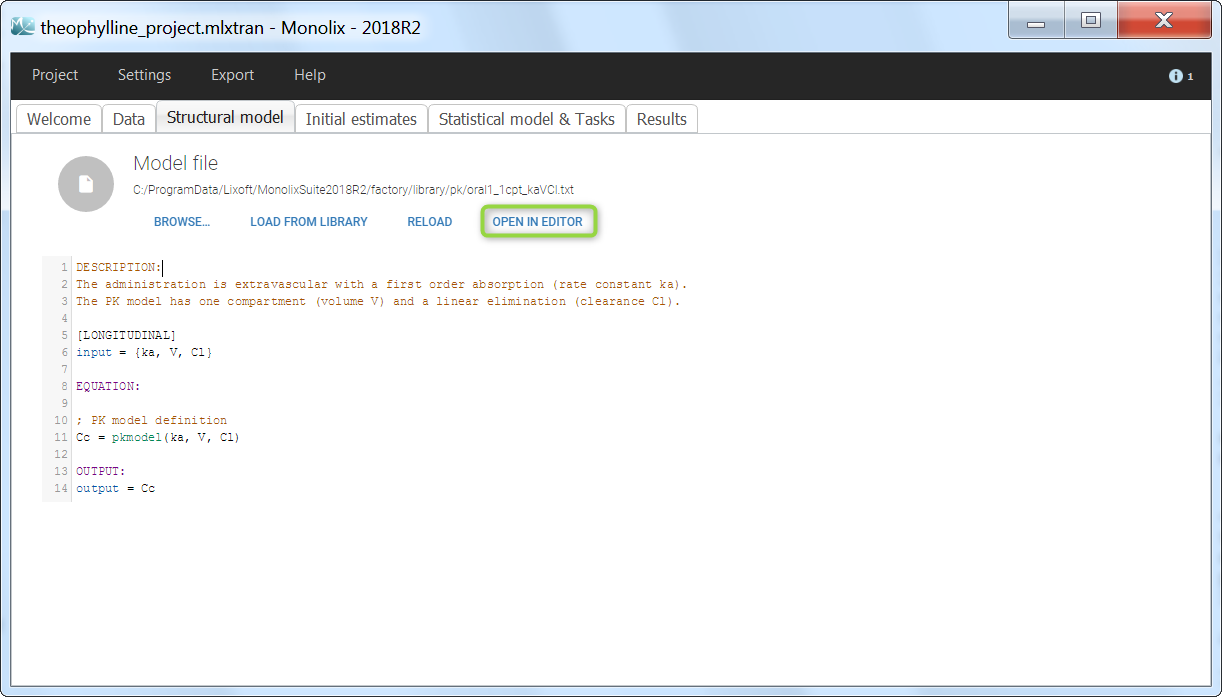

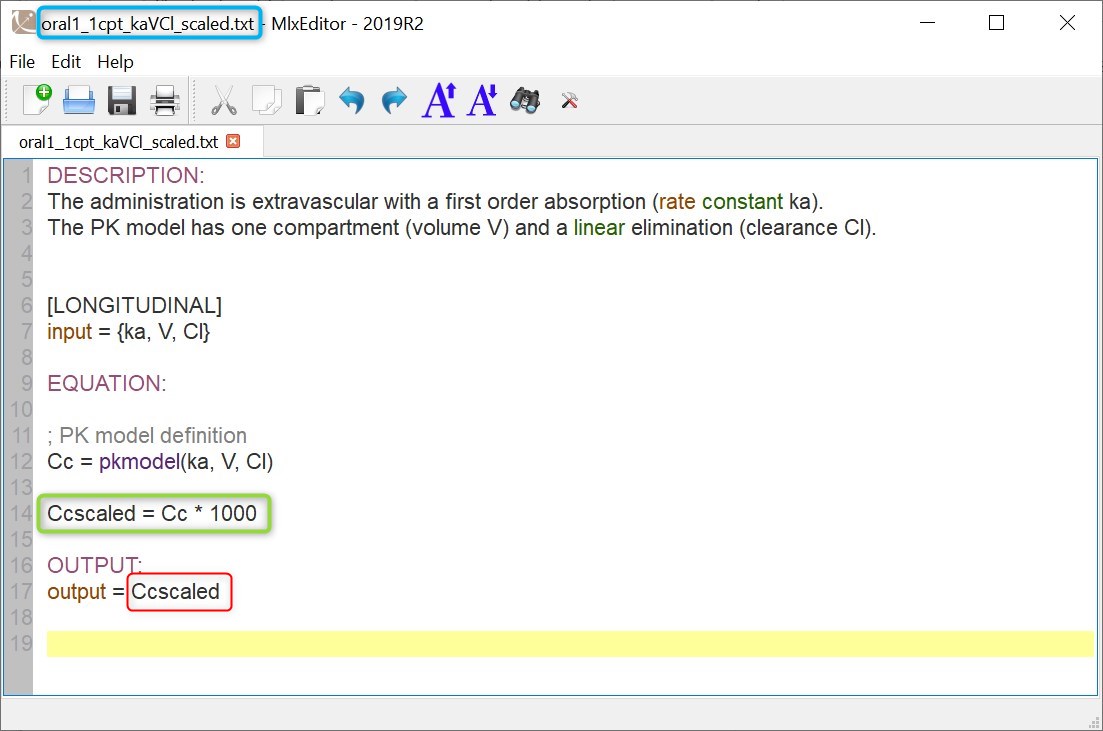

The model files are simply text files that contain pre-written models in Mlxtran language. Once selected, the model appears in the Monolix GUI. Below we show the content of the (ka,V,Cl) model:

The PK library

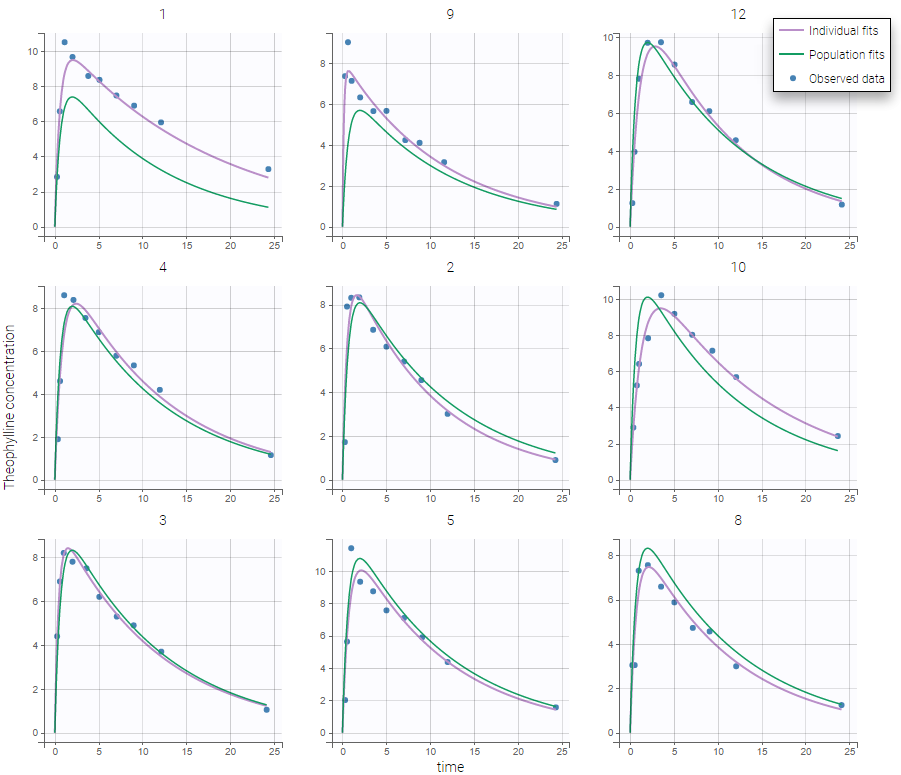

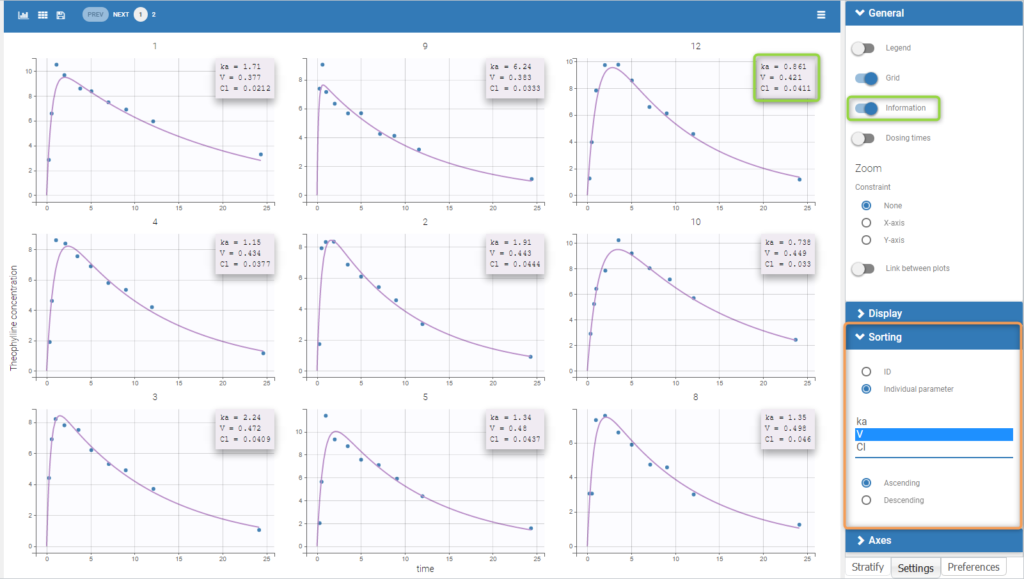

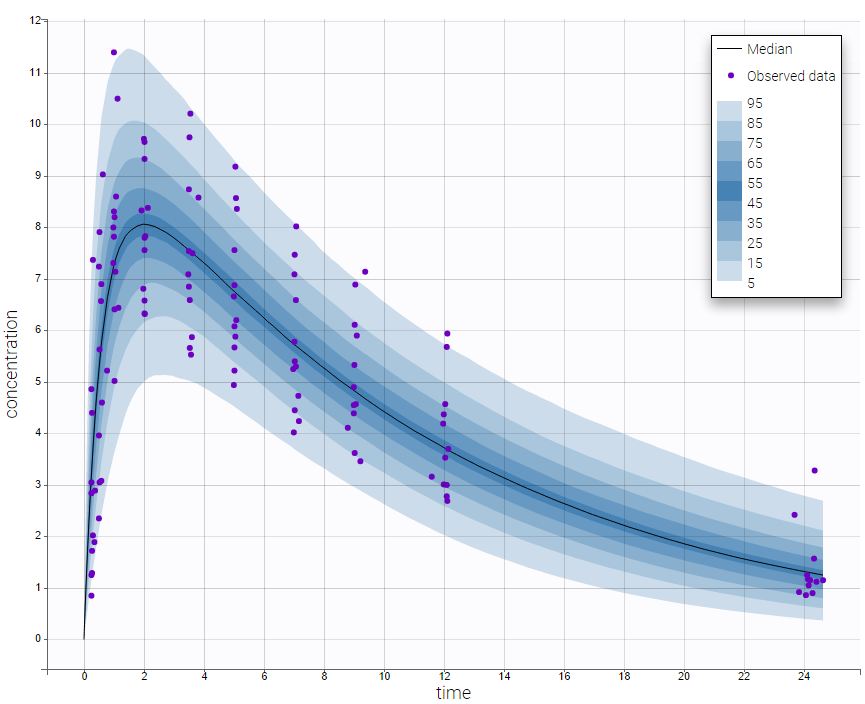

- theophylline_project (data = ‘theophylline_data.txt’ , model=’lib:oral1_1cpt_kaVCl.txt’)

The PK library includes model with different administration routes (bolus, infusion, first-order absorption, zero-order absorption, with or without Tlag), different number of compartments (1, 2 or 3 compartments), and different types of eliminations (linear or Michaelis-Menten). More details, including the full equations of each model, can be found on the PK model library wepage. The PK library models can be used with single or multiple doses data, and with two different types of administration in the same data set (oral and bolus for instance).

The PD and PKPD libraries

- PDsim_project (data = ‘PDsim_data.txt’ , model=’lib:immed_Emax_const.txt’)

The PD model library contains direct response models such as Emax and Imax with various baseline models, and turnover response models. These models are PD models only and the drug concentration over time must be defined in the data set and passed as a regressor.

- warfarinPKPD_project (data = ‘warfarin_data.txt’, model = ‘lib:oral1_1cpt_IndirectModelInhibitionKin_TlagkaVClR0koutImaxIC50.txt’)

The PKPD library contains joint PKPD models, which correspond to the combination of the models from the PK and from the PD library. These models contain two outputs, and thus require the definition of two observation identifiers (i.e two different values in the OBSERVATION ID column).

Complete description of the PD and PK/PD model libraries.

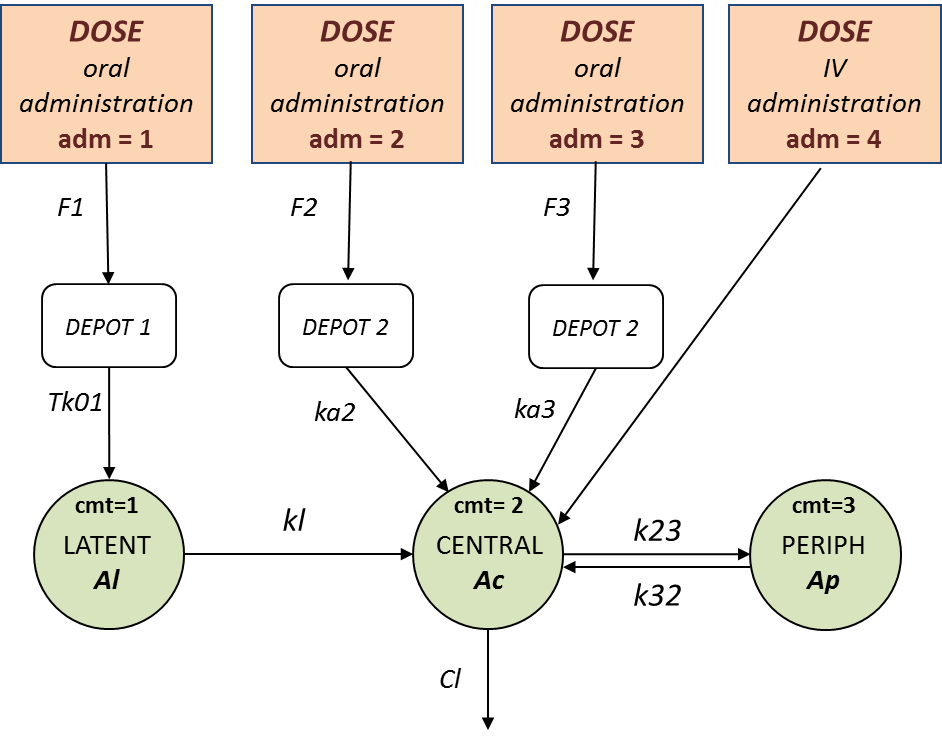

The PK double absorption library

The library of double absorption models contains all the combinations for two mixed absorptions, with different types and delays. The absorptions can be specified as simultaneous or sequential, and with a pre-defined or independent order. This library simplifies the selection and testing of different types of absorptions and delays. More details about the library and examples can be found on the dedicated PK double absorption documentation page.

The TMDD library

- TMDD_project (data = ‘TMDD_dataset.csv’ , model=’lib:bolus_2cpt_MM_VVmKmClQV2_outputL.txt’)

The TMDD library contains various models for molecules displaying target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD). It includes models with different administration routes (bolus, infusion, first-order absorption, zero-order absorption, bolus + first-order absorption, with or without Tlag), different number of compartments (1, or 2 compartments), different types of TMDD models (full model, MM approximation, QE/QSS approximation, etc), and different types of output (free ligand or total free+bound ligand). More details about the library and guidelines to choose model can be found on the dedicated TMDD documentation page.

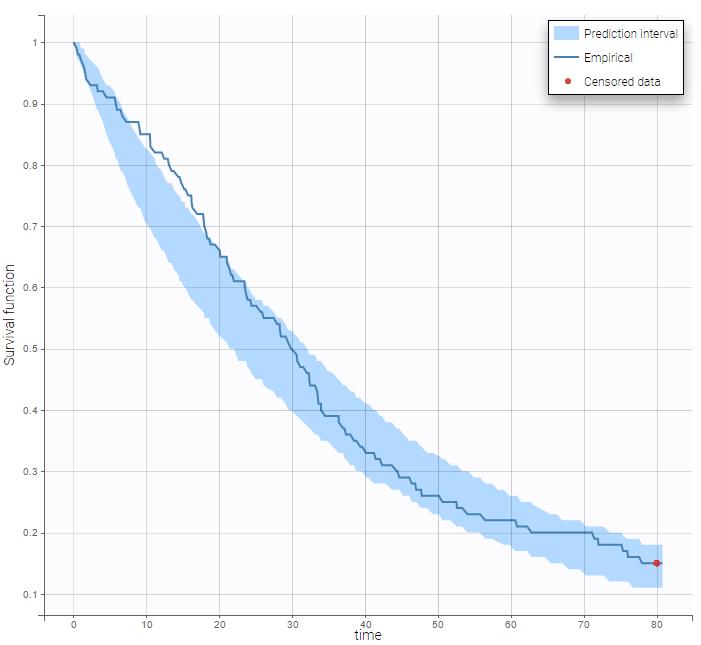

The TTE library

- LungCancer_project (data = ‘lung_cancer_survival.csv’ , model=’lib:gompertz_model_singleEvent.txt’)

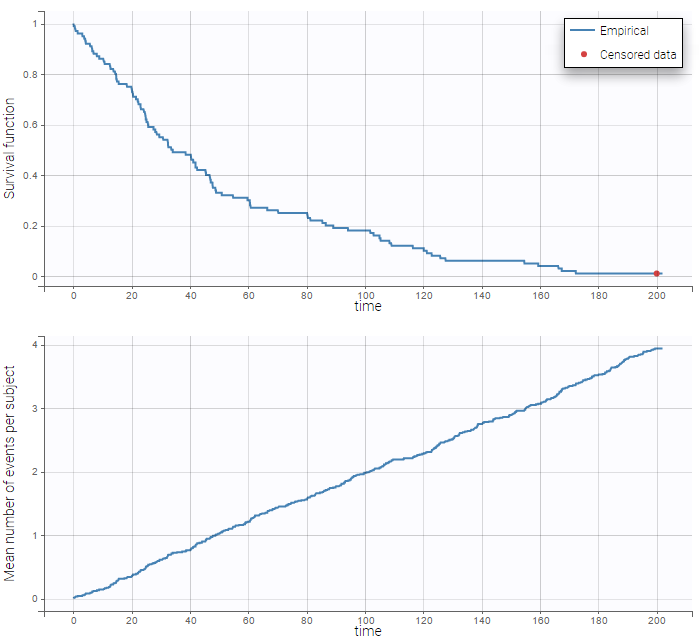

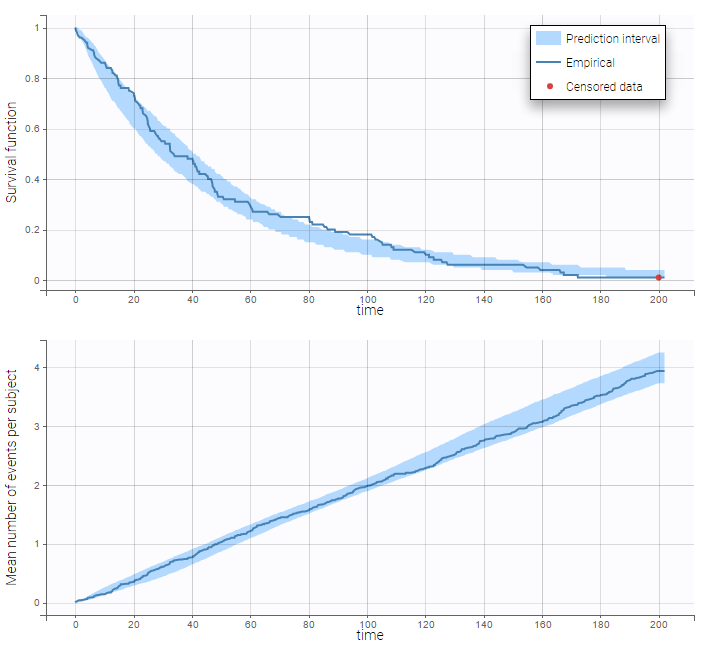

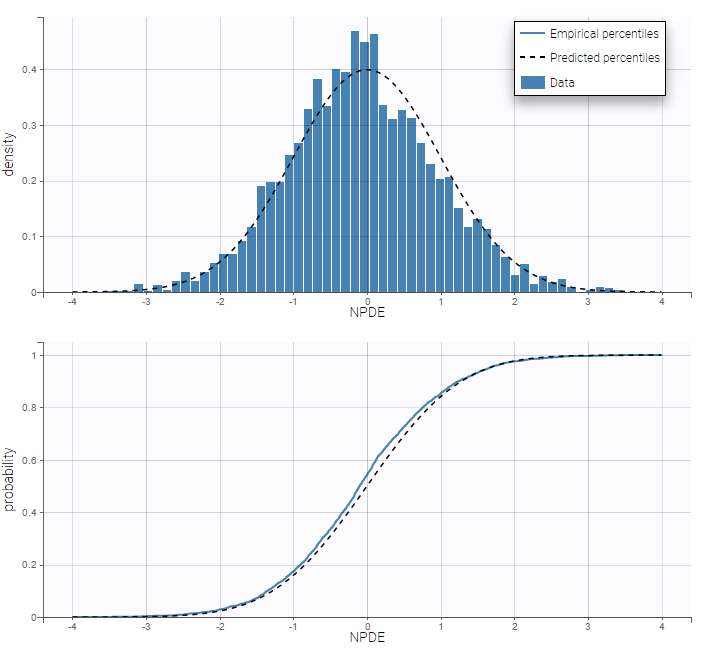

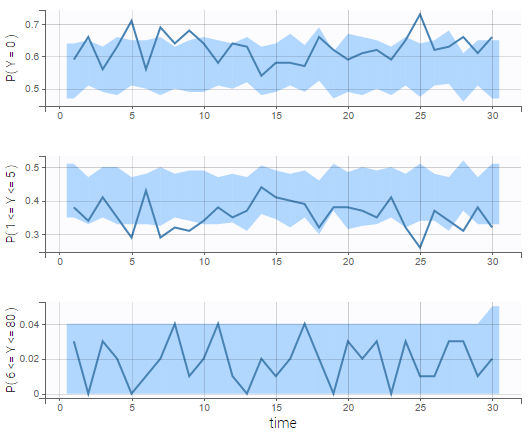

The TTE library contains typical parametric models for time-to-event (TTE) data. TTE models are defined via the hazard function, in the library we provide exponential, Weibull, log-logistic, uniform, Gompertz, gamma and generalized gamma models, for data with single (e.g death) and multiple events (e.g seizure) per individual. More details and modeling guidelines can be found on the TTE dedicated webpage, along with case studies.

The Count library

The Count library contains the typical parametric distributions to describe count data. More details can be found on the Count dedicated webpage, with a short introduction on count data, the different ways to model this kind of data, and typical models.

The tumor growth inhibition (TGI) library

A wide range of models for tumour growth (TG) and tumour growth inhibition (TGI) is available in the literature and correspond to different hypotheses on the tumor or treatment dynamics. In MonolixSuite2020, we provide a modular TG/TGI model library that combines sets of frequently used basic models and possible additional features. This library permits to easily test and combine different hypotheses for the tumor growth kinetics and effect of a treatment, allowing to fit a large variety of tumor size data.

Complete description of the TGI model library.

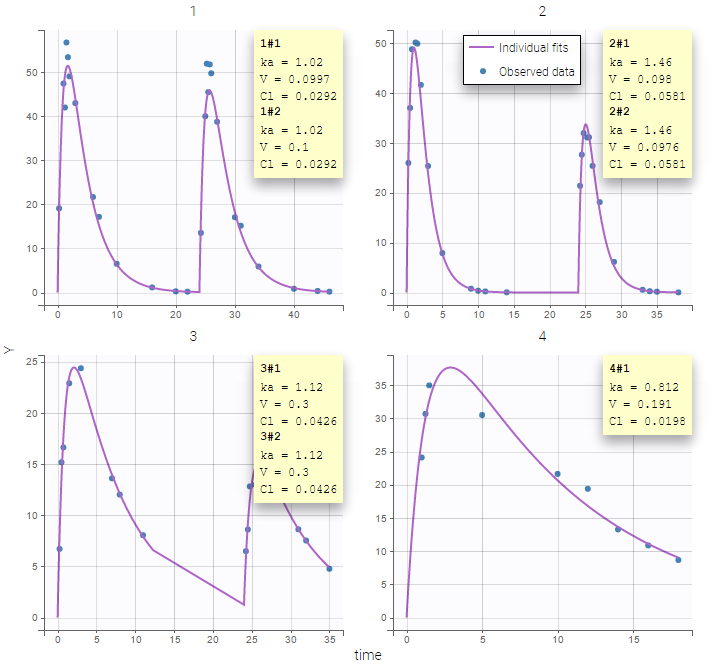

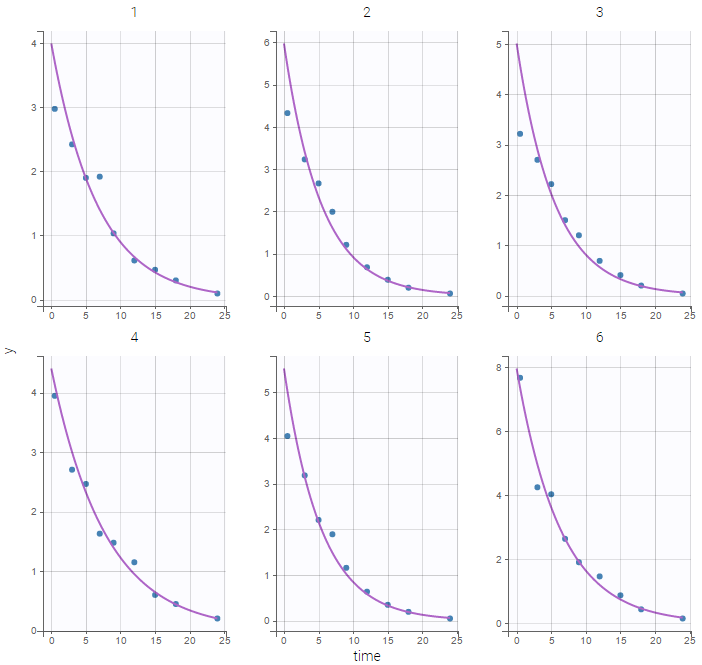

Step-by-step example with the PK library

- theophylline_project (data = ‘theophylline_data.txt’ , model=’lib:oral1_1cpt_kaVCl.txt’)

We would like to set up a one compartment PK model with first order absorption and linear elimination for the theophylline data set. We start by creating a new Monolix project. Next, the Data tab, click browse, and select the theophylline data set (which can be downloaded from the data set documentation webpage). In this example, all columns are already automatically tagged, based on the header names. We click ACCEPT and NEXT and arrive on the Structural model tab, click on LOAD FROM LIBRARY to choose a model from the Monolix libraries. The menu at the top allow to filter the list of models: after selecting an oral/extravascular administration, no delay, first-order absorption, one compartment and a linear elimination, two models remain in the list (ka,V,Cl) and (ka,V,k). Click on the oral1_1cpt_kaVCl.txt file to select it.

After this step, the GUI moves to the Initial Estimates tab, but it is possible to go back to the Structural model tab to see the content of the file:

[LONGITUDINAL]

input = {ka, V, Cl}

EQUATION:

Cc = pkmodel(ka, V, Cl)

OUTPUT:

output = Cc

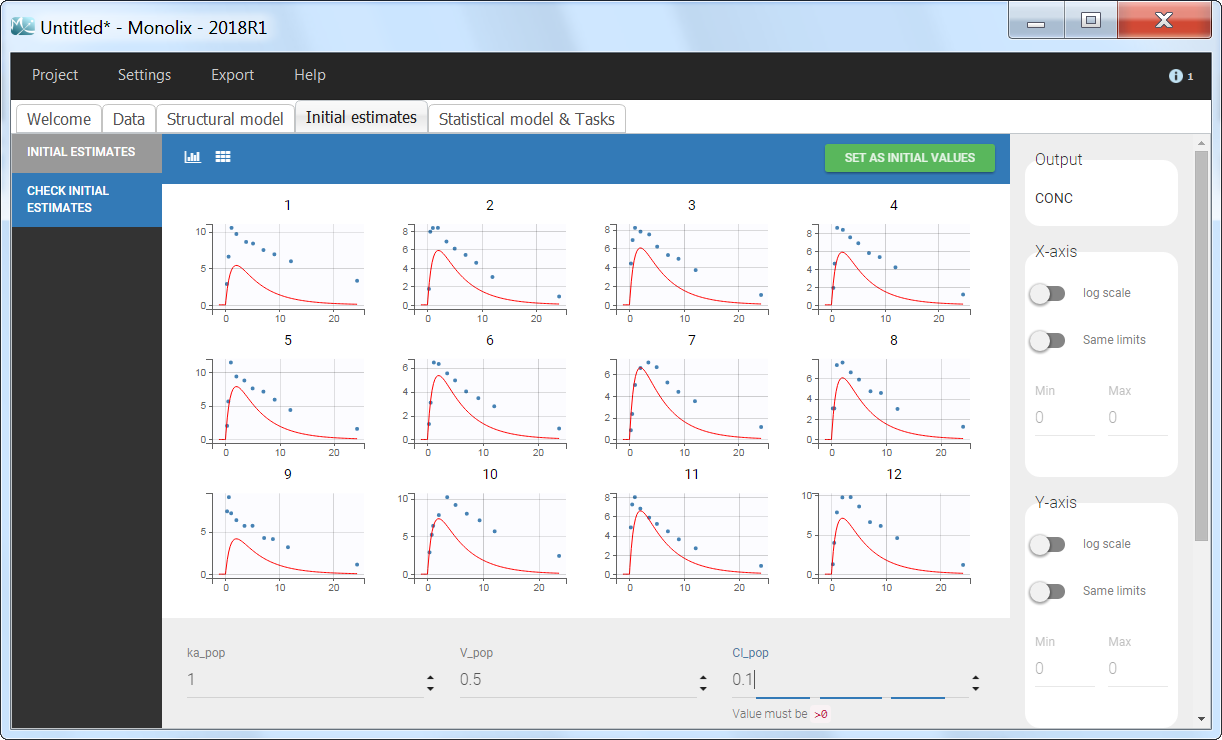

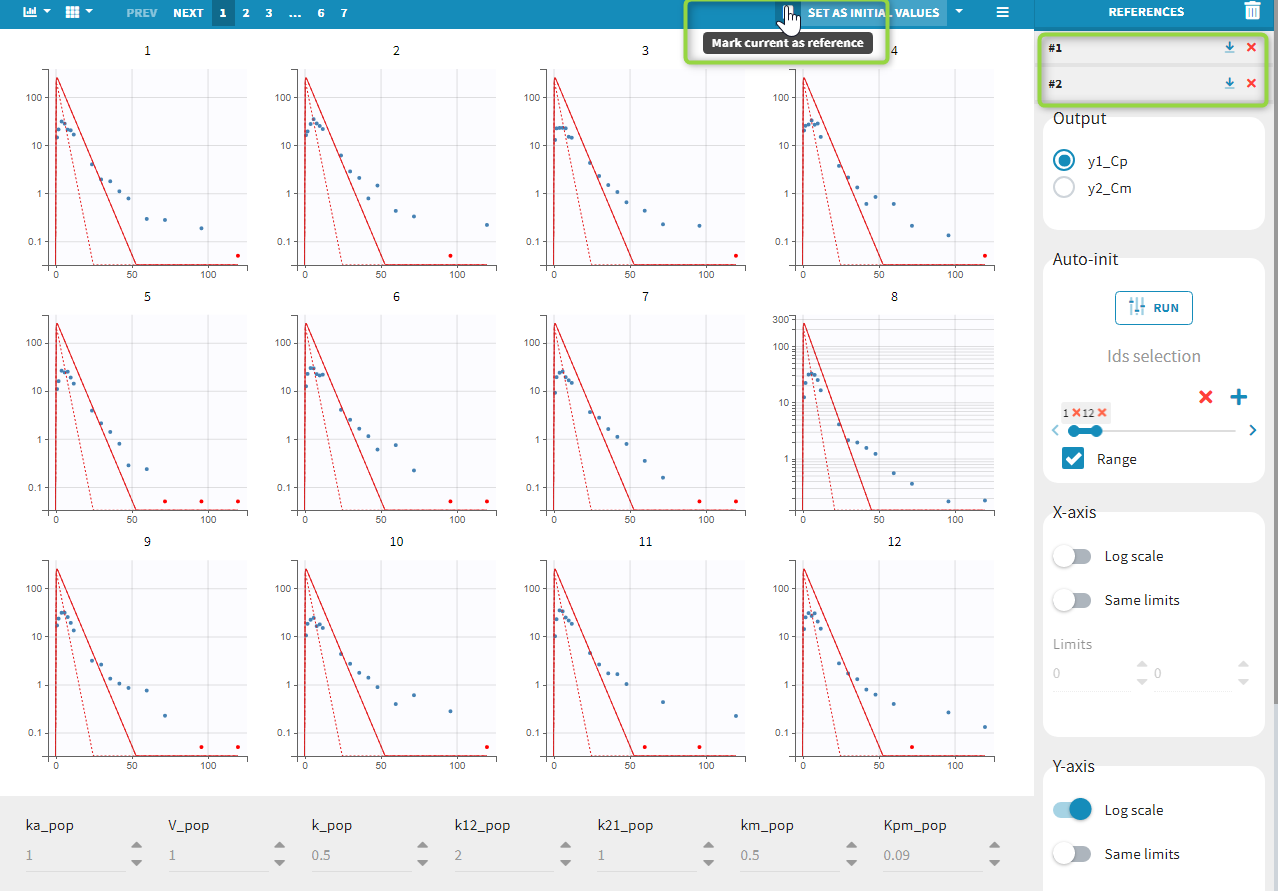

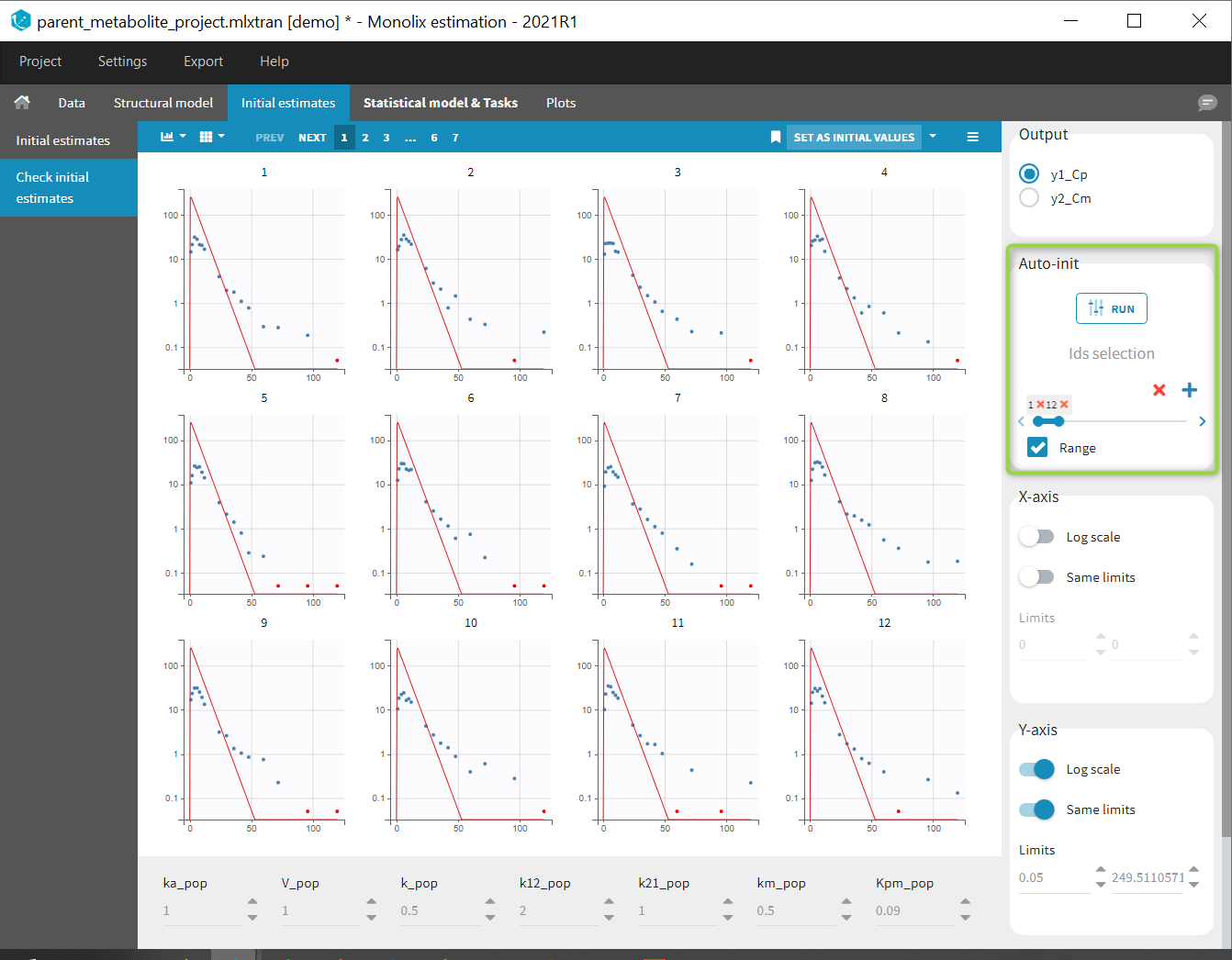

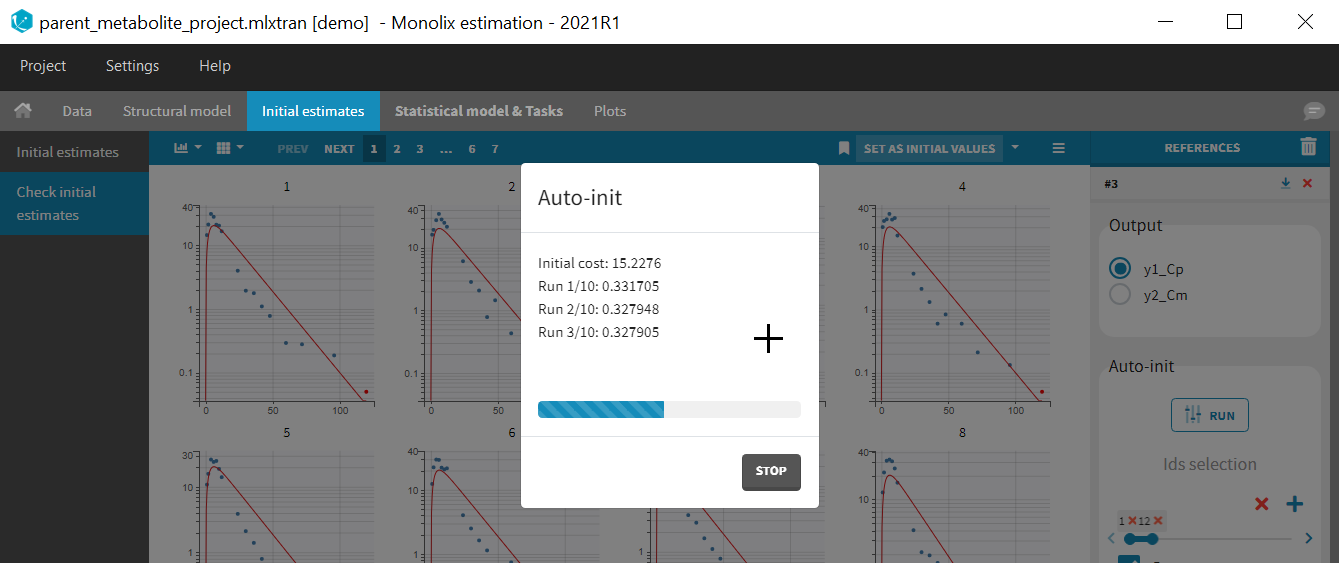

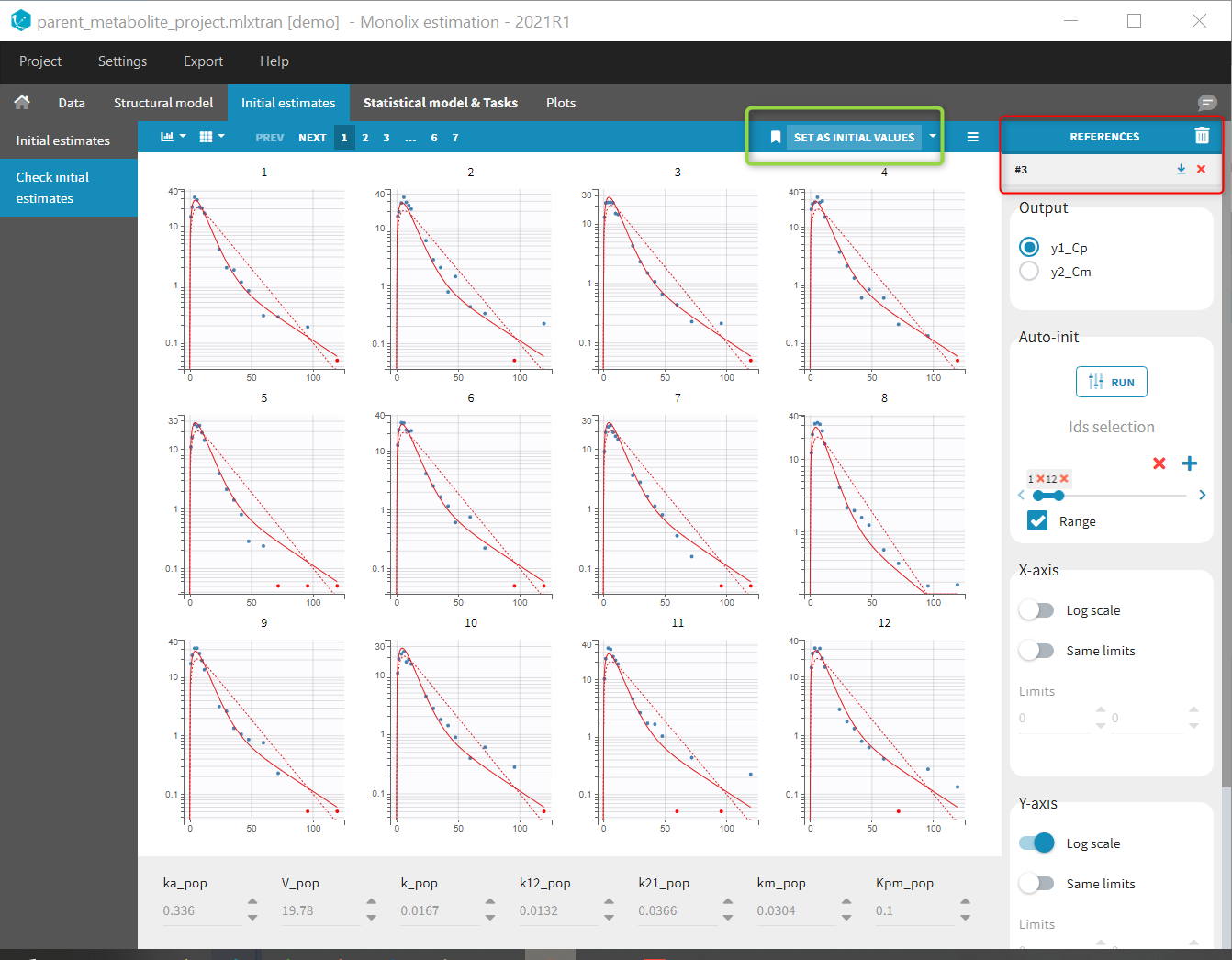

Back to the Initial Estimates tab, the initial values of the population parameters can be adjusted by comparing the model prediction using the chosen population parameters and the individual data. Click on SET AS INITIAL VALUES when you are done.

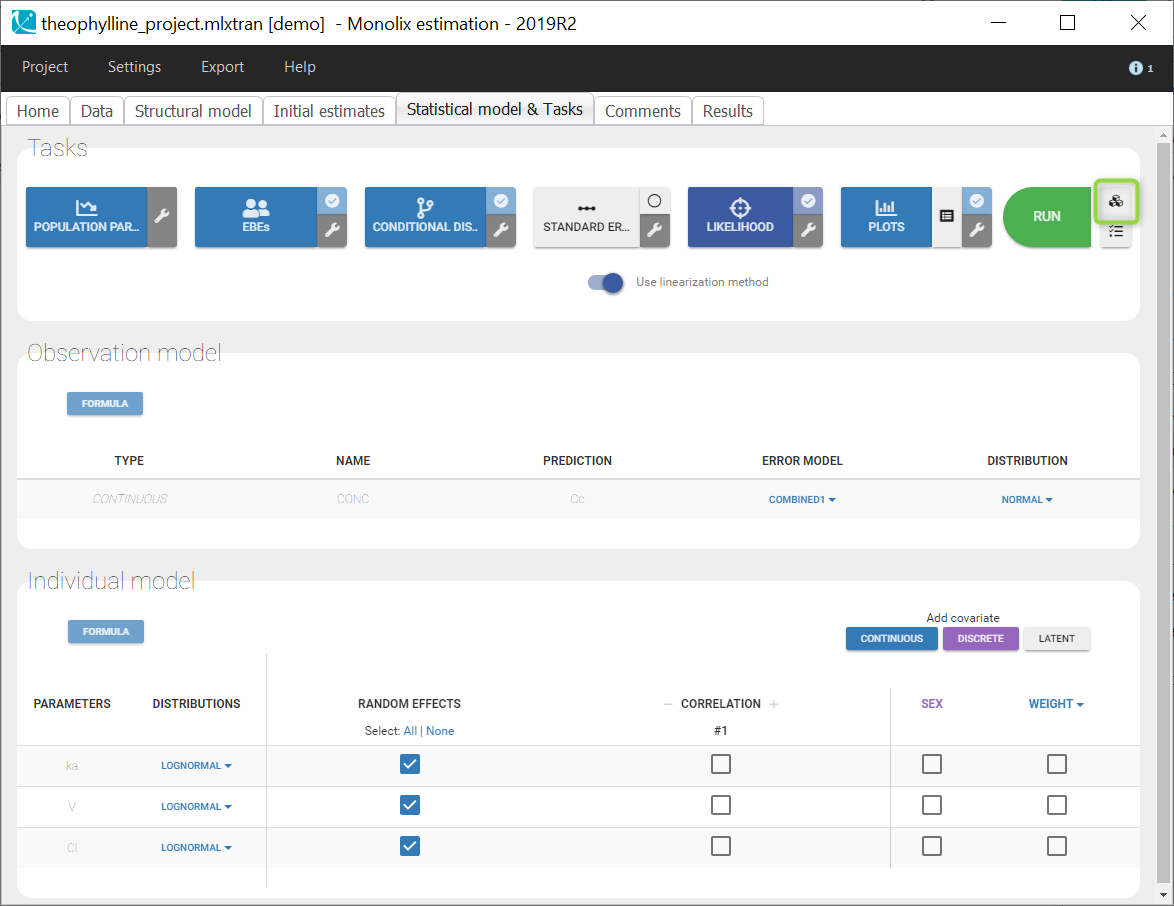

In the next tab, the Statistical model & Tasks tab, we propose by default:

- A combined error observation model

- Lognormal distributions for all parameters (ka, V and Cl)

At this stage, the monolix project should be saved. This creates a human readable text file with extension .mlxtran, which contains all the information defined via the GUI. In particular, the name of the model appears in the section [LONGITUDINAL] of the saved project file:

<MODEL>

[INDIVIDUAL]

input = {ka_pop, omega_ka, V_pop, omega_V, Cl_pop, omega_Cl}

DEFINITION:

ka = {distribution=lognormal, typical=ka_pop, sd=omega_ka}

V = {distribution=lognormal, typical=V_pop, sd=omega_V}

Cl = {distribution=lognormal, typical=Cl_pop, sd=omega_Cl}

[LONGITUDINAL]

input = {a, b}

file = 'lib:oral1_1cpt_kaVCl.txt'

DEFINITION:

CONC = {distribution=normal, prediction=Cc, errorModel=combined1(a,b)}

3.2.Writing your own model

If the models present in the libraries do not suit your needs, you can write a model yourself. You can either start completely from scratch or adapt a model existing in the libraries. In both cases, the syntax of the Mlxtran language is detailed on the mlxtran webpage. You can also copy-paste models from the mlxtran model example page.

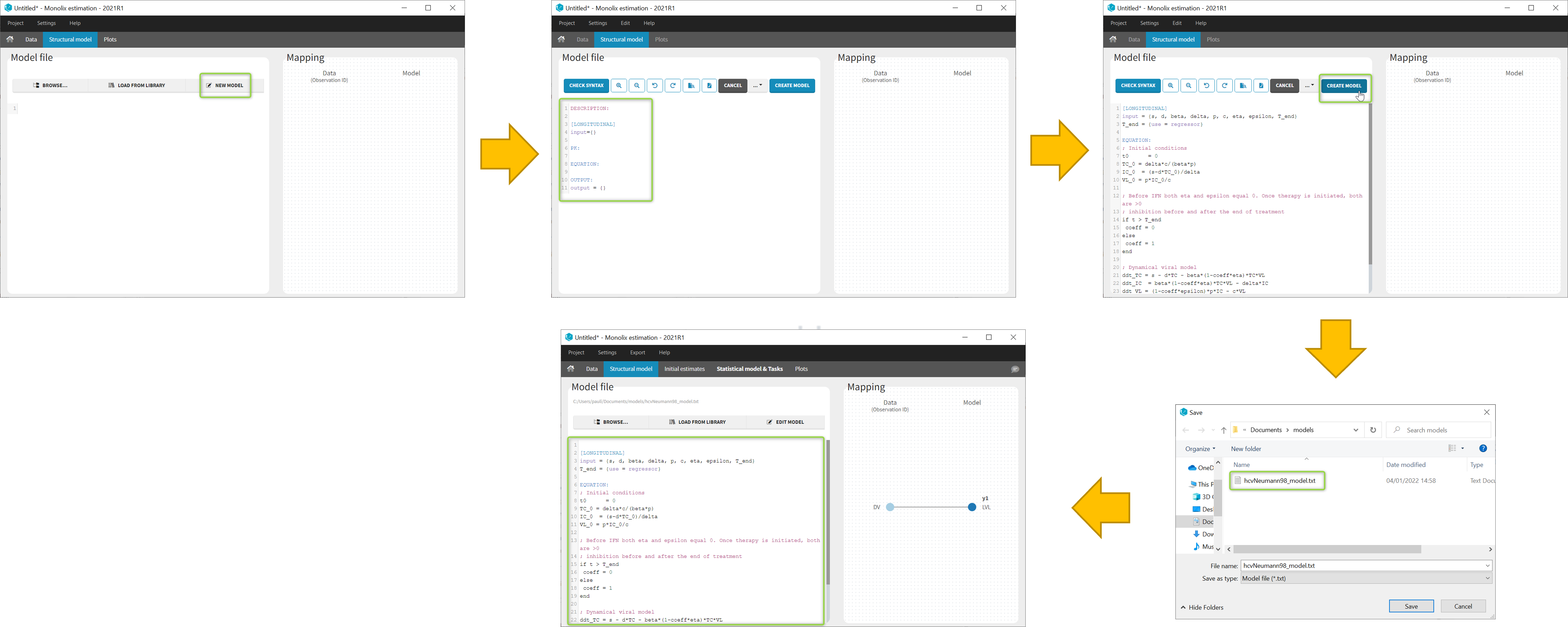

Videos on this page use the application mlxEditor included in previous versions of MonolixSuite. From the 2021R1 version on, the editor is integrated within the interface of Monolix, as shown on the screenshots on this page, and it can also be used as a separate application.

Writing a model from scratch

- 8.case_studies/hcv_project (data = ‘hcv_data.txt’ , model=’hcvNeumann98_model.txt’)

In the Structural model tab, you can click on New model to open the editor integrated within Monolix, and start writing your own model. The new model contains a convenient template defining the main blocks, input parameters and output variables. When you are done, click on Create model button of Monolix to save your new model file. After saving, the model is automatically loaded in the project.

You can even create your own library of models. An example of a basic library which includes several viral kinetics model is available in the demos 8.case_studies/model.

Note: A button “Check syntax” is available to check that there is no syntax error in the model. In case of an error, informative messages are displayed to help correct the error. The syntax check is also automatically applied before saving the model so that only a model with a valid syntax can be saved.

![]()

Understanding the error messages

The error messages generated when syntax errors are present in the model are very informative and quickly help to get the model right. The most common error messages are explained in detail in this video.

Modifying a model from the libraries

Browse existing models from the libraries using the Load from library button, then click the “file” icon next to a model name. This opens a pop-up window where the content of the model file is displayed. Click on Open in editor to open the model file in the MlxEditor. There you can adapt the model, for instance to add a PD model. Be careful to save the new model under a new name, to avoid overwriting the library files.

The video below shows an example of how a scale factor can be added:

See the dedicated webpage for more details on model libraries.

3.3.Models for continuous outcomes

3.3.1.Typical PK models

3.3.1.1.Single route of administration

- Introduction

- Intravenous bolus injection

- Intravenous infusion

- Oral administration

- Using different parametrizations

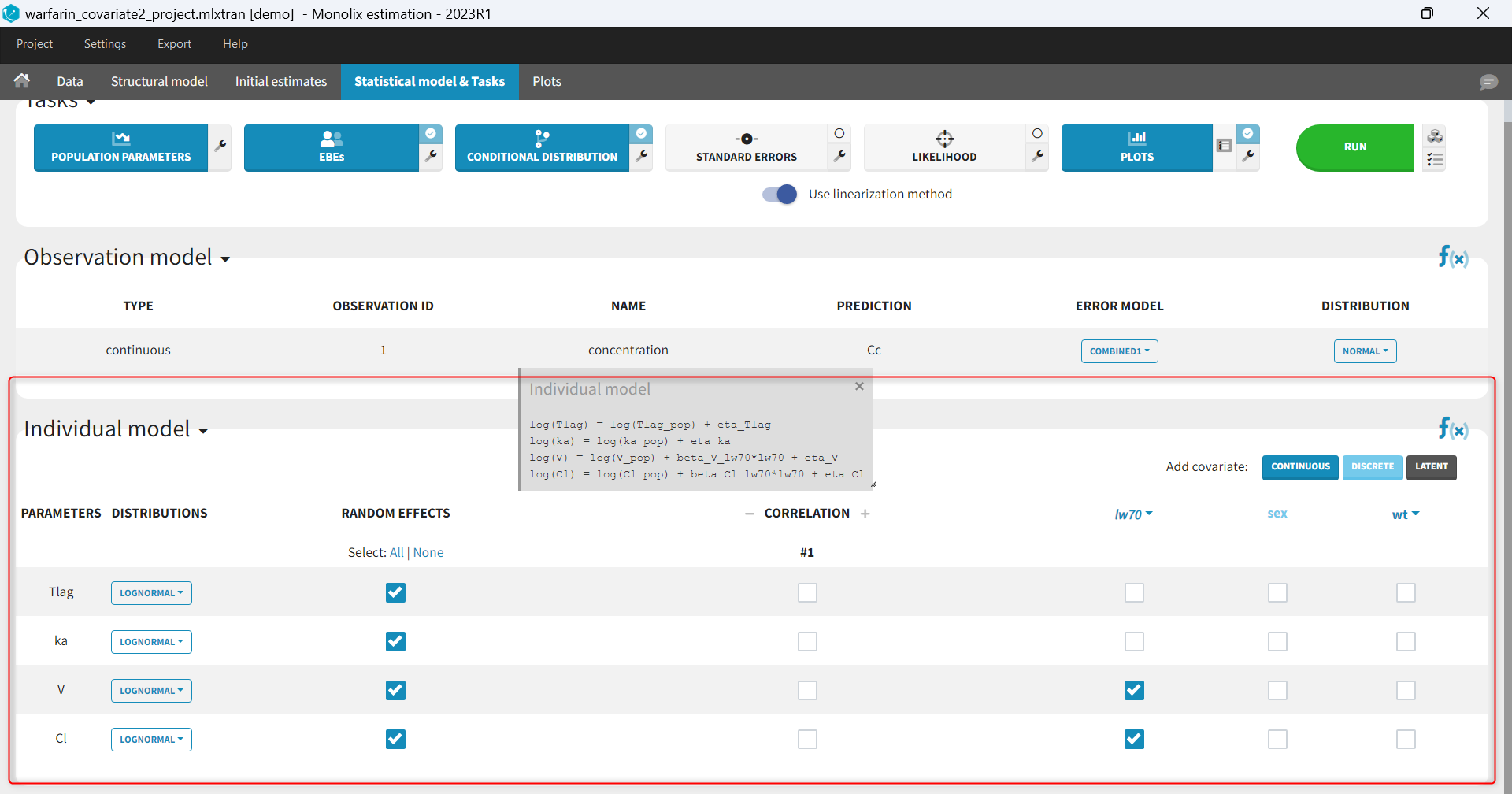

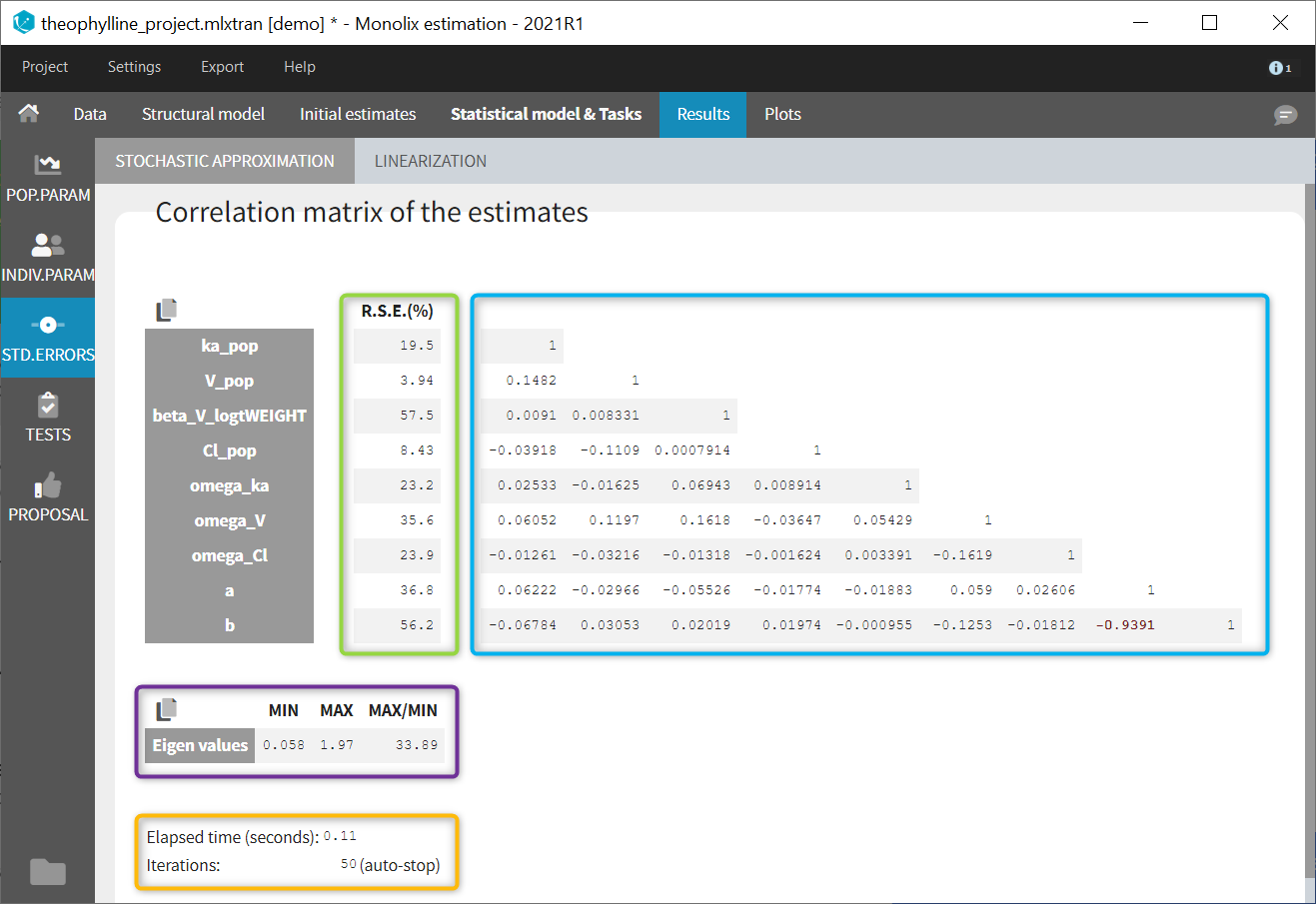

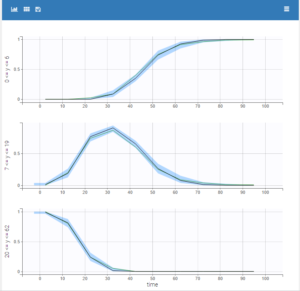

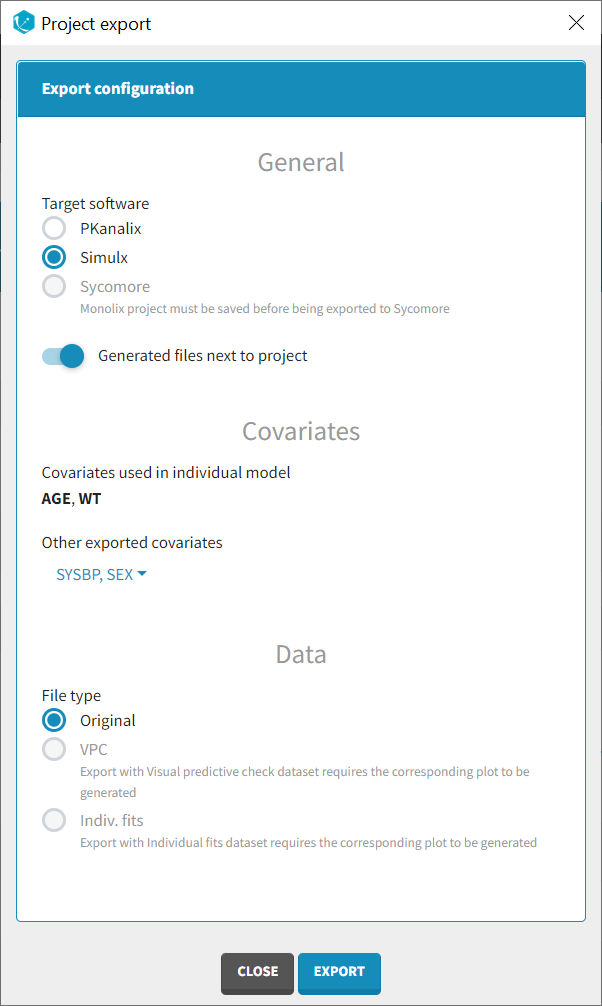

Objectives: learn how to define and use a PK model for single route of administration.